Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) was a Ministry of Defence (MoD) programme to procure a family of vehicles for the British Army that would bridge the capability gap between heavy armour and light forces.

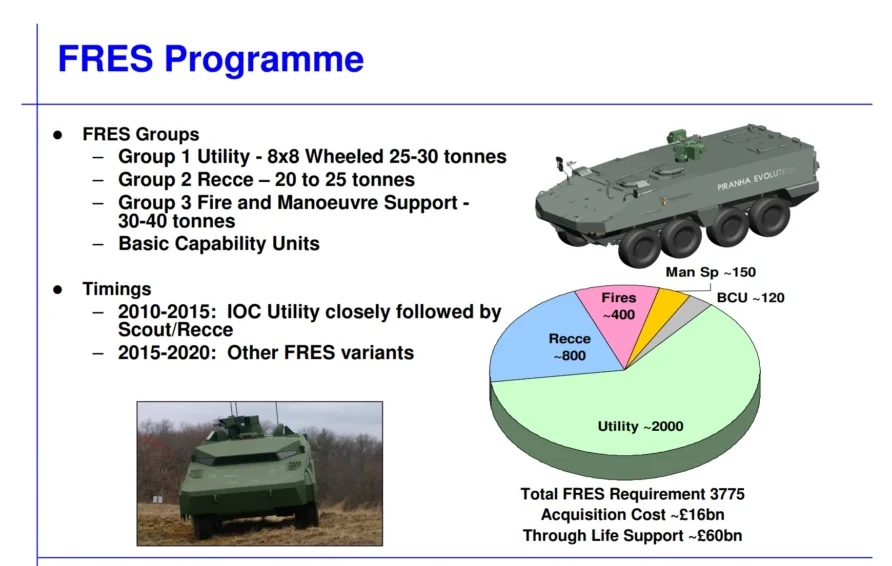

It sought to replace ageing platforms such as FV430 series, CVR(T), Stormer and Saxon, with procurement costs estimated at £13–16 billion and whole-life costs up to £60 billion.

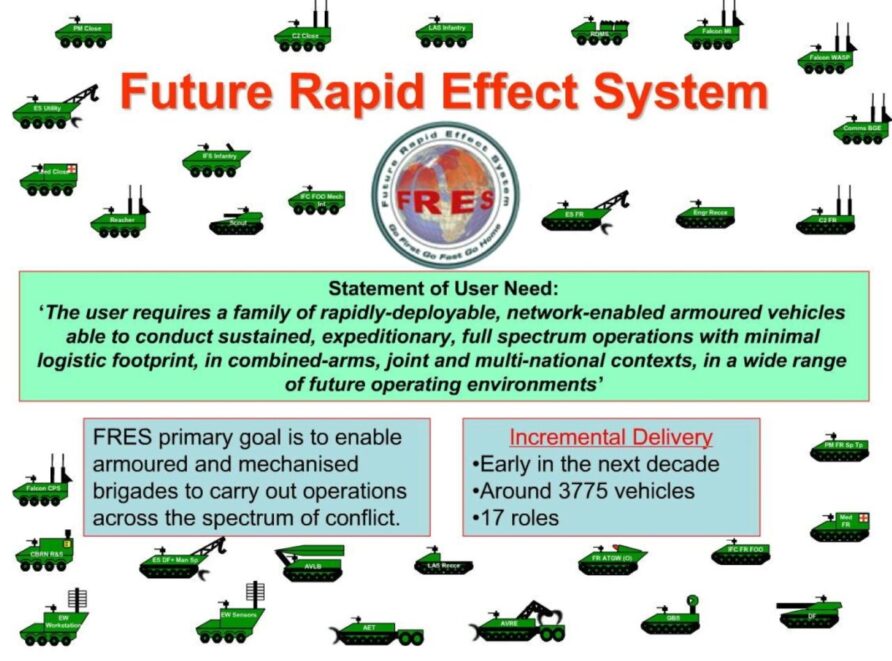

The ambitious programme encompassed five vehicle families: Utility (primarily wheeled 8×8 for protected mobility, command, and support; ~60% of fleet), Reconnaissance, Medium Armour, Manoeuvre Support (e.g., bridging/recovery), and Basic Capability.

Launched formally in 2004 after predecessor projects (TRACER and MRAV withdrawals), FRES featured an Initial Assessment Phase with Technology Demonstrators and “Trials of Truth” (2007), but faced prolonged delays, requirement changes (e.g., weight increases for protection), commercial disputes, and procurement challenges.

The overarching FRES programme was effectively cancelled in 2012 after significant expenditure, with no vehicles delivered to the field army under the original framework.

It fragmented into successors: the Specialist Vehicle strand became Ajax while the Utility Vehicle evolved into the UK’s Boxer procurement, essentially, back to TRACER and MRAV.

FRES Foundations #

To understand FRES, it is important that it is placed in the context of its antecedent programmes.

Three years after the 1982 Falklands Conflict, the British Army started work on the vehicles that would replace CVR(T), FV432, Fox and Ferret, Saxon, Saracen, and some B vehicles. Together with the Military Vehicles Experimental Establishment (MVEE) it initiated the Family of Light Armoured Vehicles (FLAV) study

Read more about FLAV here

FLAV completed in 1986, with its work included in a more formal programme called the Future Family of Light Armoured Vehicles (FFLAV), started in 1988.

FFLAV concluded that there were too many types of vehicles in service with overlapping roles and that they should be consolidated. FFLAV also included a wider range of roles and higher levels of protection for some vehicles, changing the weight classifications from FLAV.

Read more about FFLAV here.

FFLAV concluded in 1995, with a new Light Armoured Vehicle strategy that instead of the single programme envisaged in FFLAV, there would be four individual programmes.

Tactical Reconnaissance Armoured Combat Equipment Requirement (TRACER), this was a 1992 requirement.

Read more about TRACER here.

Protected mobility would be met with the Multi Base Armoured Vehicle (MBAV), itself split into two parts., defined by Mobility and Protection requirements.

M1P1 would be described as the Armoured Battlegroup Support Vehicle (ABSV), and delivered by a new variant of Warrior.

Read more about Warrior here

M2P2 would go on to become the Multi Role Armoured Vehicle MRAV (and eventually Boxer)

Read more about MRAV here.

Finally, the command and liaison requirement would be met with the Future Command and Liaison Vehicle (FCLV), this would go on to become Panther

Read more about FCLV here

Only FCLV delivered a vehicle to the British Army, Panther.

Read more about Panther here

Both TRACER and MRAV were cancelled in favour of FRES, ABSV was never progressed.

TRACER and MRAV overlap with the beginning of FRES.

There are also significant external events that influenced FRES.

First, the US Army experience in the Balkans, especially Task Force Hawk and Crossing the Sava River, and its influence on their post Cold War transformation efforts encapsulated by the Future Combat System (FCS)

Read more about the Sava River Crossing here

The rapid evolution of computing and mobile communications technology, evolving methods of reconnaissance with drones, the increasing digitisation of defence, and the 9/11 attacks in 2001 all played a part in the FRES story.

Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq would also turn out to be significant in the FRES story.

Alvis plc purchased the armoured vehicle business of the Swedish company Hägglund & Söner (often referred to as Hägglunds Vehicle AB) in October 1997. This created the subsidiary later known as Alvis Hägglunds AB (or Alvis Hägglunds).

The 1998 Strategic Defence Review (SDR) #

By the time the 1998 Strategic Defence Review was published in July 1998, TRACER had been running in one form or another for five years, and MRAV two years.

The 1998 Strategic Defence Review (SDR) committed the UK to an interventionist foreign policy,

The British are, by instinct, an internationalist people. We believe that as well as defending our rights, we should discharge our responsibilities in the world. We do not want to stand idly by and watch humanitarian disasters or the aggression of dictators go unchecked. We want to give a lead, we want to be a force for good.

It recognised a change in the post-Cold War security environment.

On the positive side, the collapse of Communism and the emergence of democratic states throughout Eastern Europe and in Russia means that there is today no direct military threat to the United Kingdom or Western Europe…The end of the Cold War has transformed our security environment. The world does not live in the shadow of World War. There is no longer a direct threat to Western Europe or the United Kingdom as we used to know it, and we face no significant military threat to any of our Overseas Territories

And that forces would need to be more joint, exploit technology and more be expeditionary.

Our future military capability will therefore be built around a pool of powerful and versatile units from all three Services which would be available for operations at short notice. They will be known as Joint Rapid Reaction Forces. From these we will put together the best force packages – with real punch and protection – for particular circumstances. To make this work, we will also need to improve our strategic transport, operational logistics and medical services, and our deployable command and control arrangements. Our aim is for the Joint Rapid Reaction Forces to be operational in 2001

It is well accepted that the 1998 SDR was a foreign policy led and well-conceived document, but it was simply not funded to its ambition.

It did not mention FRES or make any references specifically to a medium weight force, it set in train a series of projects and programmes that would include FRES, the Future Raped Effect System, and the cancellation of TRACER and MRAV.

FRES – The Early Years (2001 to 2004) #

FRES first emerged in 2001

The first mention of FRES in Hansard was in a May 8th 2001 Parliamentary Written Answer

Rapid Effects System

Mr. Key

To ask the Secretary of State for Defence what the budget is for the future rapid effects system; and if he will make a statement. [160343]

Dr. Moonie

At this stage we are considering only whether to adopt the future rapid effect system; no dedicated funding has yet been allocated to it.

The MoD issued a Request for Information (RFI) to suppliers on May 10th on how they could contribute to a medium weight force.

BAE, Alvis Hägglunds and Vickers responded, all would eventually be absorbed by BAE.

The first reference to FRES on the Internet was an article in Defense Daily International on 8 June 2001, by reporter Neil Baumgardner. It described the request for information described above.

WASHINGTON–Britain last month released a request for information (RFI) seeking information on the possible use of modified off-the- shelf vehicles as part of the Future Rapid Effects Systems (FRES) program, which intended to field a new family of C-130 deployable armored vehicles to the British army by 2007.

“The U.K. Direct Battlefield Engagement Capability Customer is migrating towards a strategic capability direction involving high tactical mobility, which is easier to deploy and sustain than that provided by present AFV (armored fighting vehicle) platforms,” according to the RFI sent to industry on May 10. “The U.K. Military Customer seeks to rationalize the future U.K. AFV programs to achieve a new platform family with a high degree of commonality.”

The British army has been moving towards the new FRES family of vehicles since the apparent collapse of the Future Scout Cavalry System/Tactical Reconnaissance Armoured Combat Equipment Requirement (TRACER) program with the U.S. Army. The U.S. Army last year decided not to proceed into the system development and demonstration phase of the program to free up funds to pay for transformation efforts focused on C-130 deployability.

The 9/11 attacks occurred on the 11th of September 2001. Special Forces and light forces from the Parachute Regiment and Royal Marines took part in the initial operations, supported by Royal Air Force and Royal Navy, the collective activity called Operation VERITAS.

In early October 2001, a statement was made to Parliament that in a joint US/UK decision, TRACER would come to a close at the end of the assessment phase in July 2002.

A second Hansard on the 26th October 2001 entry provided more details on FRES

Mr Desmond Swayne (New Forest West, Conservative)

To ask the Secretary of State for Defence

(1) if he will identify the components which make up the Future Rapid Effects System

(2) if he will make a statement on the Army’s future light armoured capability.

Dr Lewis Moonie (Parliamentary Under-Secretary, Ministry of Defence; Kirkcaldy, Labour/Co-operative) The Army’s light-armoured vehicle capability will be provided within the Future Rapid Effects System (FRES). The exact components of FRES have yet to be decided, but it is likely to include such platforms as an armoured personnel carrier, guided weapons platform, command vehicle, reconnaissance platform, ambulance and repair and recovery vehicle. FRES will draw heavily on a number of technologies developed through the TRACER programme.

The post-FFLAV TRACER programme was cancelled, leaving MRAV, but MRAV would not last long.

Although the Future Command and Liaison Vehicle (FCLV) would stand aside from FRES and continue through to the delivery of Panther, the Command and Liaison Vehicle.

TRACER came to its natural end in July 2002, at which point the FRES Integrated Project Team (IPT) was formed by the Ministry of Defence (MoD)

Alvis acquired Vickers Defence Systems (from Rolls-Royce) on 30 September 2002 for £16 million and integrated it with its existing UK operations to form Alvis Vickers (sometimes styled Alvis Vickers Ltd).

The MoD concluded that to meet the target date of 2009 (which coincided with the US FCS Interim Force) a non-competitive procurement approach was the only option available.

The approach was defined as.

- Alvis Vickers Limited (AVL) as the prime contractor

- BAE Systems as the systems engineering lead

- General Dynamics UK network integration with the British Army’s Digitisation Stage (DS2) programme

A few months later, the MoD awarded a £4 million non-competitive contract to Alvis to develop plans for the Assessment Phase of a future FRES programme

The target in-service date was to be 2009, 7 years away.

General Dynamics were also invited to contribute BOWMAN integration information to assist with developing the Assessment Phase requirements with Alvis.

The Strategic Defence Review – New Chapter was published in July 2002.

The ability to rapid deploy forces at distance was re-emphasised

We must retain the ability rapidly to deploy significant, credible forces overseas. It is much better to engage our enemies in their backyard than in ours, at a time and place of our choosing and not theirs. But opportunities to engage terrorist groups may be only fleeting, so we need the kind of rapidly deployable intervention forces which were the key feature of the SDR.

FRES was covered early in the new document.

51. But it also requires the ability to deploy and redeploy rapidly, and it has potential implications for the mix of forces that are used. For instance, some theatres and scenarios, like Afghanistan, may point towards the use of rapidly deployable light forces rather than armoured or mechanised forces and artillery: and we are examining ways of providing such forces with improved mobility and firepower. Operations in Afghanistan have again demonstrated the key role played by support helicopters. And, as part of our move towards more rapidly deployable forces, we are also pursuing the concept of a Future Rapid Effect System, a family of air-transportable medium-weight armoured vehicles. We will also be accelerating the introduction of additional temporary deployed accommodation for our troops, and further improving its hot weather capability.

Not directly connected to FRES, but part of the wider story, the Capability Manager for Information Superiority, had his plan for the delivery of Network Enabled Capabilities (NEC) endorsed in October 2002.

This may seem insignificant, but it was not.

NEC was about to be embedded in the majority of the MoD’s major equipment programmes, and FRES was not exempt.

In March 2003, after a build-up period, CVR(T), FV432 and Warrior went to war, again, with 1(UK) Armoured Division.

Speaking at the Eight European Armoured Fighting Vehicle (AFC) Symposium at the Royal Military College of Science (RMCS), Shrivenham, in March 2003, Lieutenant Colonel Neil Polley of the MoD’s FRES Integrated Project Team (IPT) described the FRES goal as

To enhance UK land forces’ capability to conduct rapid intervention, warfighting, and manoeuvre support operations through a network-capable system of platforms, allowing supremacy in battlespace awareness, command and control, precision engagement, survivability, mobility, and availability.

FRES is much more than just a platform program.

The early-stage Key User Requirements (KUR) were stated at the Symposium as,

- KUR 1 (Sustainability and Interoperability): FRES shall be able to sustain extended-duration national and coalition operation while imposing minimum logistic demand

- KUR2 (Availability): FRES shall deliver high levels of operational availability

- KUR3 (Deployability): FRES shall be easily and rapidly deployable worldwide, by land, sea and air. Much of the FRES fleet should be C-130-portable. Multiple vehicles being transportable in A400M and C-17 transports. Must be mission-capable off the ramp

- KUR4 (Operational Mobility): FRES shall be capable of self-deployment within theatre (self-deploy 300km by road, 30km on tracks, and 150km cross-country, and retain a 50km reserve)

- KUR5 (Survivability): FRES platforms shall possess a level of survivability appropriate to their role across the spectrum of conflict which (within a C-130 envelope) includes a minimum all-round protection capability against 14.5mm AP (armour-piercing) attack

- KUR6 (Lethality): FRES platforms shall be able to counter enemy capability across the spectrum of conflict, appropriate to their role

- KUR7 (Integration): FRES shall be able to integrate within the digitized battlespace fully to support C4ISTAR (command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition and reconnaissance) functionality

- KUR8 (Situation Awareness, Surveillance and Target Acquisition): FRES shall contribute key elements of the force’s Find capability to support decision superiority

- KUR9 (Environment): FRES shall be capable of operating in a wide range of environments, including complex terrain

- KUR10 (Terrain Accessibility): FRES platforms shall have high levels of terrain accessibility and tactical mobility appropriate to their role

- KUR11 (Growth Potential): FRES shall be capable of through-life capability sustainment through the ready integration of emerging technologies

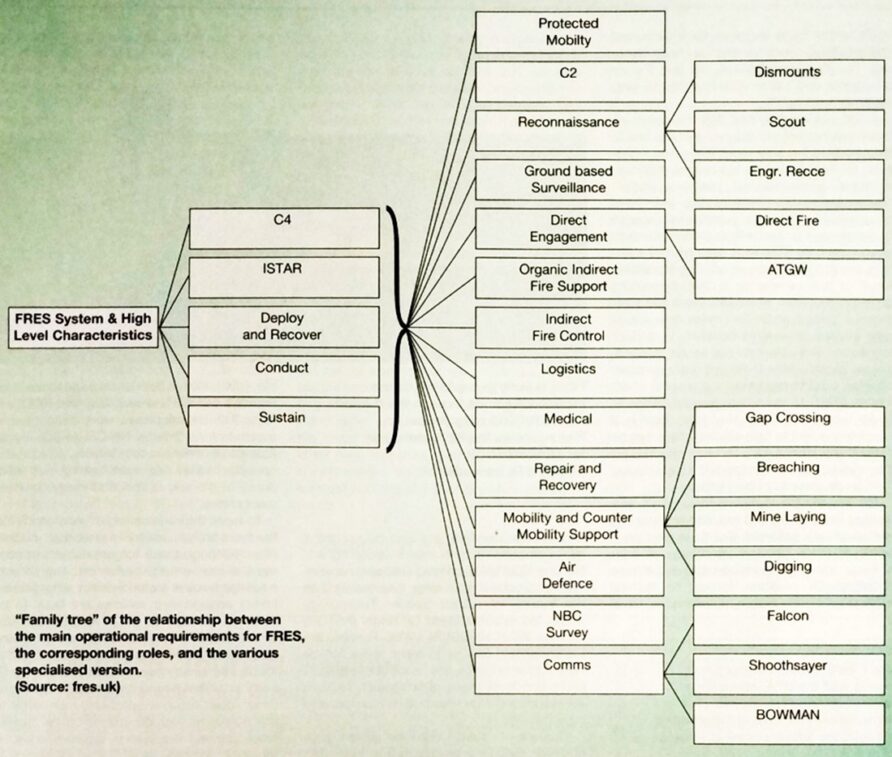

Roles described included

- Protected mobility

- command and control

- Reconnaissance (embracing engineer reconnaissance, scouting, and delivery of dismounted personnel)

- Ground-based surveillance

- Direct engagement (by direct fire and/or anti-tank guided weaponry)

- Organic indirect fire support

- Indirect fire control

- Logistics

- Medical

- Repair and recovery

- Mobility and counter-mobility support (gap-crossing, breaching, mine laying, digging)

- Air defence

- NBC survey

- Communications (Bowman radio rebroadcast, Falcon area communications system and the Soothsayer electronic-warfare system).

It was also reported that the FRES concept in this stage envisaged it immediately replacing Saxon, FV432 and CVR(T), and in the longer term, be developed to replace Challenger and Warrior.

There was some ambiguity about which variants would be (variously) deployable by C-130/A400M/C-17. There appeared to be some recognition that Direct Fire and engineering roles would be beyond a C-130 transportable vehicle.

It was envisaged the Direct Fire variant would feature a 120mm low pressure main gun, with the CV90-120 being discussed in the specialist media at the time. This early speculation also mentioned the fibre optic guided missiles, lightweight 155mm gun systems, General Dynamics Advanced Hybrid Electric Drive (AHED), and the Swedish (Splitterskyddad Enhets Platform). SEP had been in concept and development since 1994, before the Alvis acquisition.

Some early tracked design concepts images were released in June 2003.

And the APC variant

In June 2003, the Defence Main Board considered a paper from the then MoD Finance Director proposing guidance for investment priorities given MoD budget shortfalls. Priorities were suggested to included network enabled capability, deployable ISTAR, Combat identification, Nuclear, Biological and Chemical protection capabilities and logistics.

FRES was not on the priority list.

By summer of 2003, the initial FRES contract with Alvis Vickers had been terminated after the Investment Approvals Board decided not to approve the investment strategy, i.e. Alvis Vickers as Prime with BAE and GD supporting.

Major General Rob Fulton was appointed to the new post of Deputy Chief of Defence Staff (Equipment Capability) and took the view that NEC would be embedded in more or less, every single programme, FRES being no different.

It is worth at this point stepping out of the chronological sequence and quoting a couple of Very Senior Officers views on what FRES was.

An evidence session in June 2003 at the House of Commons for the Defence Select Committee provided some revealing information.

Lord Bach: Well, as to the question of whether it is a long way off or not, this is a new generation of capability that we hope to bring in. We are well equipped, we think, at the heavy end and at the light end too, but it is the medium-weight area where FRES fits in and we are moving as fast as we feel we can to initial gate approval and we hope to be able to tell you pretty soon and I will be able to make an announcement soon as to when we will. There will be some pretty cutting-edge technology with FRES when we decide exactly what it is we want out of this process and with that cutting-edge technology it is absolutely crucial that the design, the technology reaches a certain stage of maturity before we try and apply it to what will be a very expensive and a very important programme which will last for many, many years. I think it is more important that we get it right than that we rush it in, but we hope there will not be any capability gap. The General will be able to tell you whether there is a risk of a capability gap or not, but we think we have got this about right. General?

The General in question was, by then, General Fulton

Lieutenant General Fulton: I do not know about the risk.

And later in questions

Lieutenant General Fulton: You cannot go out into the world anywhere and buy FRES. The requirement for FRES is very demanding. What we are seeking to do is to put a medium-weight capability into the field which means getting many of the vehicles down to a C-130 load. We are talking of the order of 17 tonnes. This is not going to be a main battle tank in 17 tonnes because the laws of physics do not allow that. This is a medium-weight force, but the technology to which the Minister has referred is very demanding and, frankly, I do not know whether it will work because in order to get down there we are dependent, for example, on electric drive, so will that work? We are dependent on some pretty interesting technologies for protection and survivability where in order to get a level of survivability that is acceptable on the battlefield, there will be some interesting questions on situation awareness, manned and unmanned turrets, for example. What gives me confidence that we are not dragging our feet is the very, very close link that we have with the American FCS programme which is asking precisely the same questions at precisely the same time, and there are other countries doing the same, for example, Sweden’s SEP programme is also looking at that, so we, in conjunction with the American and the Swedes, clearly have an interest in producing something that is very, very similar.

Other interesting points from this

- Clear expectations that FRES was medium weight,

- The scale of the technical challenge and uncertainty in achieving technology goals,

- Close alignment with US and Swedish programmes,

- C-130 carriage as a minimum, not Future Large Aircraft (i.e. A400M) as originally.

By mid-July, the UK had formally withdrawn from the MRAV programme, citing weight and deployability as the main reasons, and that FRES would go forward instead.

The legacy of FFLAV was now only FCLV still in progress, and ABSV likewise (but destines to go nowhere). TRACER and MRAV were cancelled.

By September, the defence press was reporting that FRES vehicles would now be between 17 and 25 tonnes, with the total numbers planned to be obtained up from 1,300 to 2,800.

In October 2003, Adam Ingram again made the point that FRES was a medium weight capability in a House of Commons debate.

I mentioned the new FRES project, an exciting and important project for the Army. However, that is not to detract from the battle-winning qualities of our heavy armour. Operation Telic served to underline the crucial role that main battle tanks still possess, but that punch comes at a price in terms of deployability. We regard medium-weight forces combining ease of deployment with more firepower as an important force element for the future.

And a similar answer in response to a Written Question soon after;

In seeking a better balance in our deployable land forces, we plan to shift from the current mix of light and heavy forces representing the two extremes of deployability and combat power to a more graduated and balanced structure of light, medium and heavy forces, together with a greater emphasis on enabling capabilities such as logistics, engineers and intelligence. The introduction of the air-transportable, medium-weight Future Rapid Effects System family of vehicles is one part of this re-balancing.

Between this point and the formal launch of the assessment phase, there seems to have been some divergence between elements in the Army, the MoD Directors of Equipment Capability and the Joint Doctrine and Concepts Centre at Shrivenham.

This divergence was illustrated by the difference between the US FCS vision and FRES.

Initially, FRES was travelling in the same broad direction but with details yet to be defined, certainly, the UK vision was simpler although C-130 carriage restrictions seem to change.

As detailed requirement work started, FRES and FCS appeared to get closer.

Thus, it is important for FRES to understand FCS.

By November 2003, with work on FRES continuing, the US Army had deployed Buffalo protected IED clearance vehicles to Iraq and were readying for the first deployment of Stryker, the British Army had deployed Snatch Land Rover.

Stryker was the interim vehicle for FCS, not the objective, but the deployment was perceived by many to be a template for final version.

These units demonstrate in miniature the new American formula for war: Precise information, shared through electronic communications, enables pre-emptive action. The Stryker force’s superior awareness of the situation is meant to make up for its lighter arms and armor.

There were plenty of critics, and these generally coalesced around the simple point that whilst Stryker might be the right vehicle for FCS, it was not the right vehicle for Iraq. Stryker was deployable by C-130, but without much room for growth.

Before deployment, the vehicles were retrofitted with ‘Interim Slat Armour’ to protect against RPG warheads. Despite a number of fatal rollovers and accidents, the initial operations seemed to confirm the efficacy of the slat armour.

Also notable was a 800km road march north to FOB Pacesetter, their operational base location, and another subsequent 500km road move to Mosul. Operations in Mosul showed that the additional width and generally large turning radius made operations in urban areas difficult.

Back in the UK, the Manned Turret Integration Programme (MTIP) was a technology demonstrator working on the integration of the 40mm CTWS and a number of different sensors. A demonstration contract was placed with Cased Telescoped Ammunition International (CTAI) to complete risk reduction demonstrations on a manned turret, feed systems and other sub-systems.

CTA was required to demonstrate the CTWS in a manned turret fitted to a Warrior by the end of 2006. The French Délégation Général pour l’Armement (DGA) also placed a contract with CTA for an unmanned turret called TOUTATIS, again, to be trialled on Warrior.

With roots in the mid-eighties, 40mm CTAS/CTWS was integral to TRACER, and it seemed likely would also be included in FRES.

Read the full story of the 40mm CTAS here

The Initial Gate submission for FRES was resubmitted to the Investment Approvals Board (IAB), but approval is deferred until 2004.

The MoD awarded BAE the contract for the Future Command and Liaison Vehicle (FCLV).

Delivering Security in a Changing World – Defence White Paper was published by the government in December 2003.

It repeated many of the same arguments found in SDR new Chapter but included more information on medium weight forces

UK land forces currently consist of a mix of heavy and light capabilities. The former offer firepower, integral tactical mobility and protection necessary to carry out ground manoeuvre warfare but require a considerable effort to deploy and support on operations. Light forces in contrast can deploy rapidly anywhere in the world but lack much of the firepower, mobility and protection to conduct decisive operations against an enemy equipped with armour and mechanised forces. To increase our flexibility in responding to crises, a new set of medium weight forces will be developed, offering a high level of deployability (including by air), together with much greater levels of mobility and protection than are currently available to light forces.

It also described significant changes to Army structures.

Medium weight forces will not, however, remove the requirement for heavier armoured forces, the attributes and advantages of which were demonstrated in the conflict in Iraq. Heavy forces will continue to be held for operations where the greater protection and combat power offered by Challenger 2, Warrior and AS 90 is required. Moving to a more graduated and balanced structure of light, medium and heavy forces will over time lead to a reduced requirement for main battle tanks, other heavy armoured fighting vehicles and heavy artillery, offset by a new requirement for medium-weight forces based on the Future Rapid Effects System family of vehicles. We judge that we can reduce the size of our armoured forces now. We intend to create a new light brigade and reduce the number of armoured brigades from three to two. This new brigade will both enhance our existing intervention capability and enable the Army to meet more easily the roulement demands posed by enduring peace support tasks through the availability of an additional pool of combat forces as well as key logistics and other specialist enablers. Plans for future Army forces structures are still evolving – further details will be announced in 2004.

The White Paper also described a reduced ambition for operations at scale from SDR, but the key reduction would not come until a year later. Network Centric Capability (NCC) and Effects-Based Operations (EBO) were mentioned throughout.

By the beginning of 2004, a number of important elements to the FRES story were coming together, but Iraq would cast a long shadow.

First; the British Armed Forces had firmly embraced the emerging Western military transformational thinking, Effects-Based Operations, Network Centric Warfare, Agile Forces and Directed Logistics. Implementation was still yet to be fully realised, though. Network Enabled Capability emerged as the British version of US Network-Centric Warfare, clearly emphasising that the network would be an enabler of the other three concepts. In essence, NEC was a tactical internet, the glue that binds the others. Effects-Based Operations, after a shaky start, was renamed Effects-Based Approach to Operations in 2006.

Second; with a deteriorating security situation in Iraq, the Snatch controversy was about to break

Third; budget pressures within the MoD would influence choices on FRES and vehicles for Iraq.

Fourth; continued confusion about what FRES actually was would surface and the Directorate of Equipment Capability (Ground Manoeuvre) seemingly ignoring many in the Field Army, who wanted a simple and fast solution for FRES would lead to yet more problems.

Confusion about what FRES was would dog the programme all the way to its cancellation.

Lord Atlee posed a question in the House of Lords in January 2004

My noble friend Lord Vivian referred to FRES—future rapid effect system. Our AFV programme seems to be subject to constant revision. Is FRES a platform or a concept? If it is a platform—a vehicle on the drawing board—is it tracked or wheeled? Is it conventionally driven or electrically driven?

A question in the Commons asked something similar

Mr Andrew Robathan (Blaby, Conservative)

To ask the Secretary of State for Defence

(1) whether his Department classifies the Future Rapid Effects System programme as (a) a system and (b) a vehicle;

(2) whether the winner of the Future Rapid Effects System Systems House competition will be disqualified from playing a major role on the industrial side of the programme;

(3) whether the proposed Systems House approach is the preferred way forward for the Future Rapid Effects System programme.

Mr Adam Ingram (Minister of State (Armed Forces), Ministry of Defence; East Kilbride, Labour)

The Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) will provide a family of network-capable armoured vehicles that will form a key part of network enabled capability. We expect to make an announcement on the assessment phase for the FRES programme shortly.

From March, the security situation in Iraq deteriorated rapidly, but FRES progressed the next month.

On April 4th, 2004 the Initial Gate Business Case was approved by the MoD.

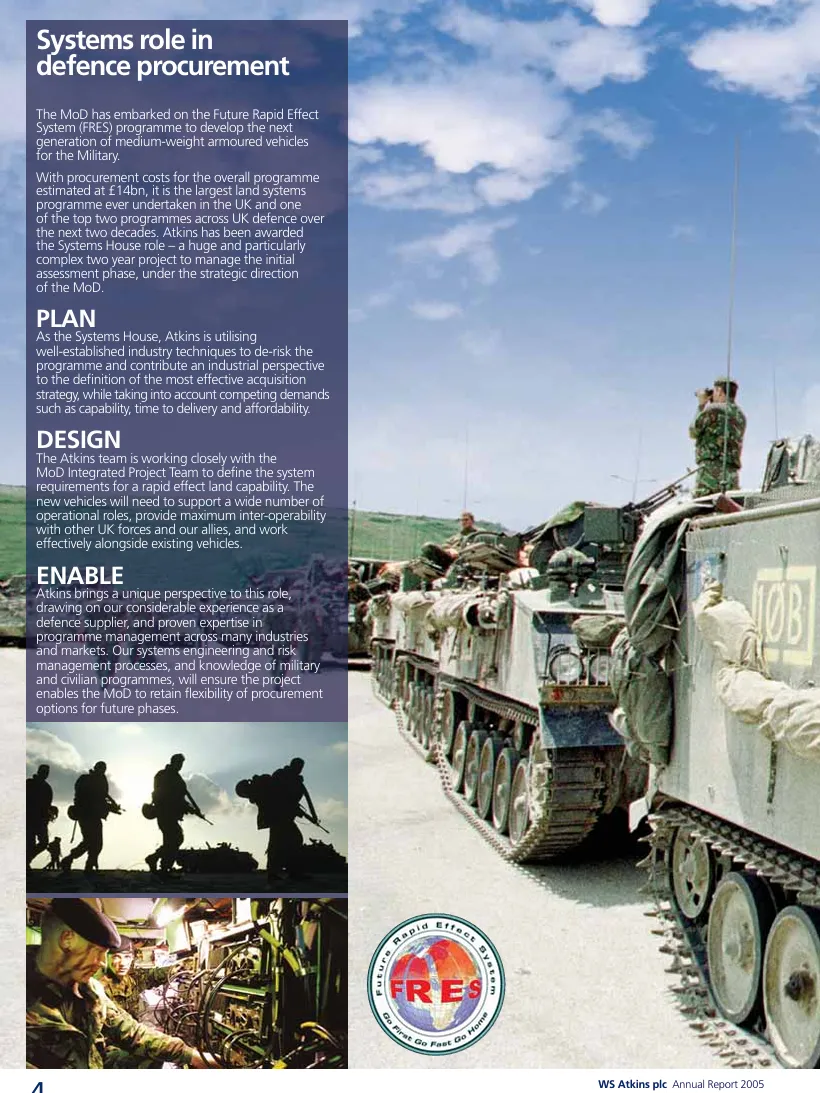

On 5th May 2004, the Minister for the Armed Forces announced a two-year Initial Assessment Phase (IAP) contract for the FRES Utility vehicle programme.

The Minister for Defence Procurement, Lord Bach, today announced the next stage of the Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) programme, the most significant armoured vehicle project for the next decade. The programme will now enter into a two-year Assessment Phase (AP).

The Assessment Phase will be led by a Systems House, independent of product or manufacturing capability, selected for their programme management, risk management and systems engineering capabilities. The Systems House will provide an objective view of the broad range of technologies and potential solutions for FRES as well as harness the broadest range of industrial capability. The two-year contract will exploit and build on previous work carried out during the initial concept stage, which laid the foundations for a successful Assessment Phase. In the coming months, the Systems House will be selected via competition and a contract should be in place by late 2004.

FRES will provide a family of medium-weight, network capable, armoured fighting vehicles with a wide range of roles. The programme is central to the Army’s future force structure, and will make a substantial contribution to the UK’s future Rapid Intervention capability. The precise number of vehicles will be determined by studies planned for the initial Assessment Phase of the programme.

Lord Bach said:

“I am confident that the Systems House approach is the best way forward for this phase of the FRES programme. It will enable us to access the widest possible supply chain as well as retaining flexibility of procurement options for the future phases. We will also ensure that UK industry is involved at every step of the way. As laid down in our Defence Industrial Policy, we are firmly committed to promoting a strong and competitive UK defence manufacturing industry. Defence industrial issues will, of course, be fully taken into account before we take the main investment decision.

“Today’s announcement is excellent news for our Armed Forces. I have no doubt that FRES will make a major contribution to the UK’s operational capability and to the UK’s future Rapid Intervention Capability”.

A short list of contenders for the Systems House included QinetiQ, WS Atkins, EDS Defence an PA Consulting.

Responding to the general confusion about FRES, General Sir Mike Jackson authored a RUSI paper to explain the Medium Weight Capability (MWCap).

He started by explaining there was an increasing requirement to intervene quickly to achieve early political and military effect and that the key element of MWCap would be FRES but that whilst there would be a resource shift to the medium weight force, It would not entirely replace light and heavy forces.

Much in the article was made of the contemporary operating environment, characterised by a diversity of operational requirements in the same theatre.

The ability to ‘nip things in the bud’ by rapid intervention by forces that were more capable than traditional lightweight forces was at the core of the concept. Although not using the same language as ‘too fat to fly, too light to fight’ it was the same argument that General Shinseki was making for FCS.

It is also fair to say that he recognised the essential ‘work in progress’ nature of the MWCap and that it is was about much more than a vehicle replacement programme.

The paper also mentioned Iraq, twice, but not in the context of enduring operations, reinforcing the criticism levelled at MWCap that it was oblivious to what was happening in the Middle East.

This paved the way for closer alignment between FCS and FRES, it’s objective.

Conducting informed discussions and information exchanges for national study, evaluation and assessment efforts for the purposes of investigating capability gaps, exploring opportunities for requirements harmonization, improving understanding of Participants’ national LBS programs, and identifying areas of potential cooperation or for use in national LBS programs to enhance Participants’ interoperability.

May 2004 saw the first recorded use of an explosively formed projectile (EFP) IED against UK forces, against a Warrior in the Maysan province.

Writing in the Summer-2004 edition of the RUSI Journal, William F Owen described what he saw as one of the main problems of FRES;

Defining or explaining FRES is no easy task. The name itself adds to the confusion. What is an ‘Effects System’? The name comes from the ill-defined and unhelpful concept of separating capability or effect from platform.

William F Owen made the point that FRES was clearly a vehicle, or platform, not a concept.

FRES thought industry must be left to describe how it would deliver the effect, the MoD was simply to articulate what that effect was.

In response to a Written Question, the Governments confirmed the acquisition costs of FRES would be £6 billion, with through life costs estimated at £49 billion.

In evidence to the Defence Select Committee Nick Prest, the then Chairman of Alvis, made somewhat of a large understatement;

in the armoured vehicle area I think it is fair to say that the MoD has had particular difficulty in formulating its requirements, launching procurement programmes and then sticking to them

In mid-2004, the projected In-Service Date for FRES was 2009.

28 June 2004, Fusilier Gordon Gentle of the 1st Battalion, Royal Highland Fusiliers was killed by a roadside bomb whilst travelling in a Snatch Land Rover in Basra.

In September 2004, BAE Systems integrated Alvis Vickers with its existing RO Defence (Royal Ordnance) division to form the new BAE Systems Land Systems business unit.

BAE Systems also created a dedicated FRES team in September.

On the 16th of November 2004, the MoD formally announced the Systems House contract to Atkins.

Essentially, Atkins would be the middle man between the MoD and industry and for the IAP, with no ties to any vehicle or systems manufacturers, the MoD expected a bill for £120 million, with a focus on risk reduction and requirements definition.

Atkins built a 70-strong team to manage the two-year programme.

Atkins was also tasked to let the competitive Technology Demonstrator Programme contracts to industry as part of a FRES Integrated Technology Acquisition Plan (ITAP).

The MoD stated that because Atkins was outside the normal military vehicles supply chain their independence and engineering rigour would keep the MoD honest, but almost immediately after they were appointed, anecdotal evidence emerged about the issues this lack of domain knowledge would cause.

One example described an Atkins project manager phoning the BAE switchboard and asking for advice on what an Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) was, for example.

All anecdotal, though.

The intent was for Atkins to subcontract specialist assessment work but contribute to an overarching Combined Operational Effectiveness and Investment Appraisal (COEIA)

Geoff Hoon announced the creation of the ‘Future Army Structure’ on December 16th, 2004.

The term warfighting crept into the official lexicon.

The major changes described were the cessation of the Arms Plot, a reduction of 4 infantry battalions to 36 and a number of mergers and disbandments.

He said:

These plans will make the Army more robust and resilient, able to deploy, support and sustain the enduring expeditionary operations that are essential for a more complex and uncertain world. The move to larger, multi-battalion regiments that these changes bring about is the only sustainable way in which to structure the infantry for the long term. We must consider these changes to the infantry in the wider context of the need to rebalance the Army, and the opportunity it affords to reallocate manpower to those areas that we need to develop. The Army has always evolved to meet current and future challenges. I am convinced – and so is the Army – that this transformation is the right course. The future Army structure will deliver an Army fit for the challenges of the future.

Nearly two years into the Iraq campaign, the government was shaping the Army for enduring operations, not the quick in and out nip things in the bud vision that underpinned FCE and FRES from 2000.

The announcement also confirmed a number of equipment projects would go forward or be sustained, despite this change of vision, FRES continued.

Tens of billions of pounds worth of new hardware will be procured to help the military to continue to perform so outstandingly. Incoming systems include: Skynet 5, Cormorant and Falcon communications systems, the Watchkeeper unmanned aircraft, the Astute class submarine, the Type 45 Destroyer, the FRES family of armoured vehicles, and the large CVF aircraft carriers.

The Army was to have a structure based on two Heavy Brigades (CR2 and Warrior), 3 Medium Brigades (FRES) and 1 Light Brigade (Boot Combat High) plus Air Assault and Commando Brigades.

In December 2004, a number of ITT’s were issued to industry by Atkins for ten Technology Demonstrator Programmes supporting FRES.

- Chassis Concept (includes self-digging & suspension)

- Electronic Architecture (includes C4I, vetronics, HUMS, integrated image handling, local SA & SIL)

- E-Armour

- Integrated Survivability

- Capacity and Stowage

- Hard Kill DAS

- Regenerative NBC

- Band Track

- E-drive

- Gap Crossing

These were defined by the FRES Integrated Technology Acquisition Plan (ITAP)

FRES TDP’s and the Trials of Truth (2005 to 2007) #

In April 2005, a FRES Fleet Workshop was held to refine vehicle requirements.

A TDP contract awarded to Akers Krutbruk in May 2005 for hard-kill defensive aids (to December 2006).

At the 5th Annual Future Combat Vehicle Conference at RUSI on June 8th 2005, Brigadier Bill Moore, Director Equipment Capability (Ground Manoeuvre) provided description of the various UOR’s and capability enhancement in progress and an update on the Medium Weight Capability and FRES.

He confirmed that thinking on C-130 transportability had changed

A400M and C-17 will dictate the weight and size limits for FRES. We estimate only seven to seventeen C130’s will be in service by the in-service date for FRES

At the same event, General Sir Mike Jackson, Chief of the General Staff, said:

Many of the platforms in service are often twice as old as the young soldiers manning them. This has to change and FRES means to do that

Because Boeing were involved with the US FCS programme, they also had an interest in FRES. They were a sponsor of the RUSI conference.

Dennis Muilenburg, programme manager for FCS at Boeing, said

We could use the experience harnessed from FCS to benefit the FRES programme. We believe there is too much useful information from FCS for it not to be used in FRES

During a parliamentary debate on the 28th of June 2005, Don Touhig (Parliamentary Under-Secretary (Veterans), Ministry of Defence; Islwyn, Labour) revealed a number of interesting facts about FRES in response to a question from Ann Winterton MP, reproduced in full below;

It might be helpful if I clarify what FRES is. I shall outline the drivers for the requirement, and give details of the progress that we have made in an immensely complex and demanding programme. The underlying requirement for FRES stems from two strategic requirements. First, we need to replace some of our current armoured vehicles, such as the Saxon, the FV 430 and the CVR(T), and, secondly, we need to develop a medium-weight capability so that we have a balanced force of heavy, medium and light brigades.

FRES will also be rapidly deployable by air at battle group level—in other words, a battalion or regiment-sized force. The strategic defence review and its new chapter identified the need to enhance our expeditionary capability, but since then our thinking has developed further. The 2003 and 2004 defence White Papers clearly explain our vision to develop a highly effective medium-weight capability. As a result of the review, the Army will be rebalanced, reducing the emphasis on heavy armoured forces and increasing the emphasis on light and medium forces.

By ensuring that each deployable brigade is fully manned and has its own integral enablers and logistics, the Army will be better equipped and structured to conduct all types of operations. FRES is at the heart of the Army’s equipment programme and it will have wide uses, not only in the medium forces, but also as a key support role for our heavy forces.

Whether for short intervention operations or enduring peace support, we often need forces with greater firepower, protection and mobility than that of light forces, but with deployability and agility that cannot be achieved by heavy forces. By providing this capability, FRES will underpin the rebalancing of the Army and the development of a truly effective medium-weight force.

In a nutshell, FRES will be a family of medium-weight armoured vehicles of around 20 tonnes, enabled by communications, information and surveillance systems, with the growth potential to develop over time. It will be the central pillar of the Army’s capable and deployable balanced force, which will have a wide operational role, from warfighting to peacekeeping.

To help the hon. Lady, I can say that the issue of whether the vehicle is wheeled or tracked is under consideration as part of the assessment phase we are going through at this time.

FRES will fill a wide range of combat and support roles. Those roles will range from a vehicle to provide protected mobility for infantry, through command and control vehicles, to a new scout vehicle for reconnaissance tasks. These medium-weight armoured vehicles will mean that FRES will be significantly lighter than our current heavy armoured forces based on the Challenger 2 and the Warrior armoured infantry fighting vehicle, but I should make it clear that FRES will not replace Challenger 2, Warrior or the AS 90 guns in our heavy forces.

FRES will take full advantage of investment in our communications and information systems network. We intend that it should be network capable; it will not provide the network, but it will contribute to it. It will make full use of network-enabled capability. By this I mean that it will provide the coherent integration of sensors, decision makers and weapons systems through communications and information systems. That will enable FRES to perform roles such as command and control, dissemination of intelligence and situational awareness and control of firepower.

FRES is a complex and demanding programme. The requirement is broad and covers a wide range of military capability. We will need to take a pragmatic view of how to balance some of the individual requirements, such as combining high levels of protection and low weight, or large capacity and small size. The programme will need to interface with a range of existing and planned equipment if we are to deliver the full benefits.

Beyond the equipment programme, the Army will also need to consider the programme’s wider implications, such as the impact it will have on doctrine and how the Army trains. Given this complexity, we are approaching the programme with a careful, rigorous and objective assessment of the technical options. We will consider industrial issues and the acquisition strategy, as well as the broader implications for the Army of bringing FRES into service and, of course, the risk.

As part of the current assessment phase, which began last year, the FRES integrated project team assisted by Atkins, an independent systems house, is investigating those and other issues to ensure that FRES is cost-effective, value for money and successfully delivered. Until we make the main investment decision, time, cost and performance parameters will not be set. We will take that decision only when we are confident that the programme is mature enough to provide accurate answers to the issues that I have outlined.

The hon. Lady asked whether the 2010 date for the introduction of FRES was purely a coincidence, and from the Government’s point of view, it is. She also asked whether FRES is affordable. Affordability is a key factor in the assessment phase. Costs will not be formally approved until the main investment decision point. We currently expect FRES to have an approximate total procurement cost of £14 billion. The hon. Lady also made some important points about the use of FRES in urban areas, and the lessons that we have learned in recent conflicts will be taken into account throughout the assessment and planning stage.

To take the project forward, we have identified a series of planning assumptions that provide a basis for the planning of FRES and for interacting programmes. As new information emerges from the assessment phase, those assumptions may evolve, but under our current assumptions, we expect FRES to deliver about 3,500 vehicles, with the first variants entering service early in the next decade.

The assessment phase is now well under way, with technology risks being addressed through rigorous systems engineering work and a number of technology demonstrator programmes. So far two such programmes have been placed: a contract for capacity and stowage has been placed with the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory and a contract for defensive aid suites is with Akers Krutbruk. Another five contracts—two for the chassis concept, two for the electronic architecture and one for electric armour are currently being negotiated.

In parallel, the systems engineering work has developed a number of fleet options, which are now being assessed in more depth. The acquisition strategy will be critical to the successful delivery of FRES. Industrial capacity for armoured vehicle design, integration, manufacture and assembly is clearly key to the programme.

In the context of defence industrial policy, we will need to consider a wide range of issues, including employment. We must also assess the importance of retaining a UK industrial capacity and capability which, at a minimum, allows us to maintain and upgrade current and future equipment. The Defence Procurement Agency is currently considering how we can achieve that while delivering value for money.

As the hon. Lady suggested, another issue to consider is the scope for co-operation with other nations, including in the context of the European Defence Agency’s initiatives. We are clear, however, that current FRES timelines must be maintained. No decisions on co-operation between FRES and other nations’ armoured vehicle programmes have yet been made, nor do we expect to make any before the main investment decision point. I should also reassure the hon. Lady that FRES will not be dependent on the European satellite navigation system, Galileo, which is a civil programme under civil control.

FRES is a key programme for the Army and for defence and it is vital to fully achieving our vision of a rapidly deployable medium-weight capability. Its complexity means that we would be rash to rush into decisions before we have fully investigated all the issues. By following best practice, which is enshrined in the smart acquisition initiative, the programme is moving forward and it has considerable momentum. It remains a cornerstone of our future equipment programme.

Since the assessment phase started last year, a huge amount has been achieved. Atkins, the systems house, has been appointed and integrated into the FRES team. The system’s engineering process has begun to narrow down the options, and the development of an acquisition strategy has begun. The technology demonstrator programmes are under way and more will start soon. A wide range of firms were informally engaged through a highly successful industry day in January.

FRES will be an important enhancement to our defence capability, and I hope that, as debate continues, we will be able to share our plans and ideas with people such as the hon. Lady. She has taken a considerable interest in the matter, and, again, I thank her for raising the issue today.

Although a long statement, it made clear a number of issues that had seemingly plagues the external perception of FRES.

- The rapid deployed by air element was only at Battalion or Battlegroup level, not as many have subsequently claimed, whole brigades, for which the UK simply did not possess the air transport fleet for

- Confirmed of expansion of the medium weight capability at the expense of light and heavy forces

- FRES would be ‘significantly lighter’ than the current heavy forces and Challenger, Warrior and AS90

- An in-service date of 2010 at a cost of £14 billion.

The LANCER Consortium TRACER vehicle made a brief re-appearance in the UK in June 2005 to demonstrate the joint Horstmann and L3 Electronically Controlled Active Suspension System (ECASS). ECASS was an advanced development that smoothed bumps and controlled roll at speed using suspension actuators acted both as motors and generators, compensating by adding or removing energy. Energy storage was handled by a combined battery/capacitor unit that also had the beneficial side effect of reducing the heat build-up normally associated with conventional shock absorbers and springs.

It was though there might be some pull through from TRACER into FRES.

The General Dynamics 8 x 8 Advanced Hybrid Electric Drive (AHED) test vehicle was also demonstrated in the UK in June.

AHED used a hybrid electric power system and in hub motors.

A month later, General Dynamics were awarded an 18-month Wheeled Chassis Technology Demonstrator Programme contract by Atkins, the Systems House.

General Dynamics Corporation (ticker: GD, exchange: NYSE) News Release – Wednesday, August 24, 2005 020 7932 3400

LONDON, United Kingdom – General Dynamics United Kingdom Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of General Dynamics (NYSE: GD), has signed a contract with Atkins, the UK Ministry of Defence’s System House, for the Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) Chassis Concept (CC) Technology Demonstration Programme (TDP).

FRES CC TDP is an 18-month program to demonstrate the readiness of in-hub electric-drive and its ability to meet the FRES platform requirements, as well as the integration of a third party Electronic Architecture (EA) into the chassis. It is also an opportunity for the team to demonstrate its ability to work with Atkins in meeting the program’s timeline and information requirements for Main Gate approval. General Dynamics’ Advanced Hybrid Electric Drive (AHED) 8×8 will provide a baseline from which to evaluate the integration challenges and potential benefits of transformational technologies for the Future Rapid Effect System program. Developed by General Dynamics, the AHED already has over 4200 km of road and cross-country testing. General Dynamics intends to conduct over 4500 km of additional reliability testing for the FRES CC TDP. Its interchangeable modular in-hub electric drive, and hybrid power architecture will dramatically reduce logistics footprint and whole life cost of ownership associated with unique components, large repair part inventory and training for both operators and maintenance personnel.

“We are delighted to have won a FRES Chassis Concept TDP contract,” said Sandy Wilson president and managing director of General Dynamics UK Limited. “AHED provides a ‘best value’ point of departure for designing a FRES family of vehicles that is based on a common chassis and sub-systems for a family of vehicles fleet. The design flexibility enabled by the open architecture and on-board power provide a platform that can be adapted to the FRES roles in a variety of configurations, depending on the mission or requirement profile.

“Our target is to deliver demonstrable evidence to our customer that in-hub electric-drive is mature enough to meet the FRES requirement and that the hybrid power architecture can be successfully integrated with an open standards electronic architecture. Further, this is an excellent opportunity for the customer to evaluate the transformational benefits of a hybrid-electric drive that offers track-like performance at wheeled vehicle costs, which has the capability to quickly balance or shift power to mission systems that may have different requirements based on mission profile. This optimizes performance for fuel efficiency, and removes traditional armoured fighting-vehicle drive line constraints, which will significantly reduce the whole-life cost of ownership.”

The General Dynamics UK FRES industry team comprises General Dynamics UK Limited (project lead), and General Dynamics Land Systems, Sterling Heights, Michigan, USA.

AHED had a 500hp diesel engine and large battery system that powered in hub electric motors.

In July 2005, a Preliminary Fleet Review to assesses current armoured vehicles against FRES requirements was held.

BAE established a Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) capture team at Farnborough in the summer to ensure all elements of the BAE organisation could be bought into proposals for future FRES Technology Demonstrator Programme (TDP) contracts.

In August 2005, TDP contracts awarded to General Dynamics UK for chassis concept (to March 2007) and to Lockheed Martin UK and Thales for electronic architecture, both to run to March 2006.

Thales and BAE teamed up for the Electronic Architecture TDP, awarded in September 2005, to run to March 2007.

BAE then proposed that the Swedish SEP (Splitterskyddad Enhets Plattform) or Modular Armoured Tactical System) programme might be exploited for FRES.

At this point, the tracked and 6×6 platforms were being tested after being funded by the Swedish Defence Matériel Administration (FMV). With BAE by now in ownership of Hägglunds, the synergies seemed obvious.

Tracked SEP weighed 17 tonnes, had a payload of 6.5 tonnes and maximum speed of 85 km/h. It also featured an advanced hybrid electric drive and a modular payload system that was common to both the tracked and wheeled chassis.

By the end of 2005, BAE had been awarded the second Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) chassis concept Technology Demonstrator Programme (TDP) contract to investigate the potential for SEP to increase in weight to 28 tonnes, despite the earlier confirmation that FRES would be around 20 tonnes.

The Integrated Survivability Technology Demonstrator Programme (TDP) contract was awarded to Thales and an Electric Armour TDP to Lockheed Martin.

BAE also won the Gap Crossing and Electronic Architecture TDP’s.

The 2005 FRES year was rounded off with the publication of the Defence Industrial Strategy., Chapter 3.

The most likely solution (for FRES) will be a team in which national and international companies co-operate to deliver the FRES platforms, including the required sub-systems, led by a systems integrator with the highest level of systems engineering, skills, resources and capabilities based in the UK. We expect to see a significant evolution of BAE Systems Land Systems both to deliver AFV availability and upgrades through life, and to bring advanced land systems’ technologies, skills and processes into the UK. If successful in their evolution, BAE Systems will be well placed for the forthcoming FRES programme”

This was closely followed by the AFV Partnering Agreement between BAE and the MoD that was designed to improve value for money and ensure the UK’s access to intellectual property in the AFV domain.

BAE invested its own funds to develop the 8×8 version of SEP, and Atkins published their annual report with a whole page devoted to FRES.

A FRES fleet review took place in January 2006

It concluded no off the shelf vehicle would meet the FRES requirement and that the earliest in-service date would be 2015 to 2018 if the Army’s survivability and growth requirements were to be realised.

It also concluded that whilst the US Stryker could be obtained for the Utility Variant, it offered insufficient protection, lacked growth potential and the UK would be unable to make any modifications.

Stryker was therefore discounted from further consideration.

BAE then made released plans to establish a Systems Integration Laboratory (SIL) at their Leicester site and Platform Development Centre in Newcastle to meet the requirements of FRES.

Also in March 2006, Jane’s reported a conversation with Brigadier Lamont Kirkland (Director of Land Warfare) that described how the experience of US and British forces in Iraq had led to a major shift in thinking on FRES.

The MoD and industry alike were talking 17 to 22 tonnes for FRES for four years, only in the last four months had those involved with the programme taken a collective leap in levels of protection

The new baseline weight was 25–30 tonnes, beyond the capability of the C-130 but well within that of the FLA/A400M, confirming what Brigadier Bill Moore said at RUSI in June 2005, 9 months earlier.

The General Dynamics AHED 8×8 had completed the second phase of its Chassis Technology Demonstrator programme at 18 tonnes and was preparing for the final stage at an increased weight of 20 tonnes.

Jane’s went on to confirm.

Before the invasion of Iraq – and more specifically the coalition stabilisation mission that followed and which continues today – the future of the UK’s armoured capability was expected to centre around a medium-weight force of rapidly deployable vehicles. Now, however, the reality of operations in a largely urban environment against an asymmetric threat has forced a complete re-evaluation of the degree of acceptable risk to an armoured vehicle’s survivability.

The vehicles had shifted up several tonnes but, doctrinally, it appeared there was little change except for a reduction in variants.

17 was now 16, the air defence version having been removed.

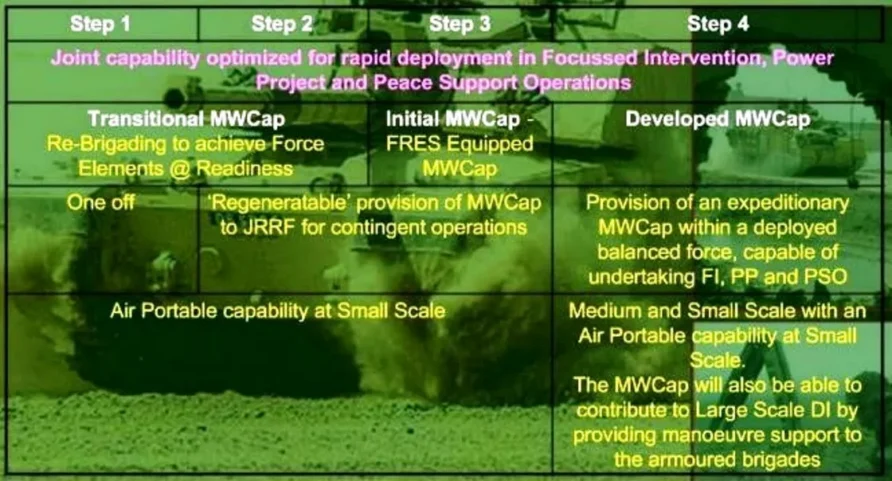

The Medium Weight Capability strategic intent was defined as.

MWCap is an effects-based military capability made up of Joint Force Elements and optimised for Focused Intervention, Power Projection and Peace Support Operations.

MWCap will be air portable at small scale for rapid deployment within 7 days to the core regions. At Medium Scale, MWCap may act as the first echelon of a larger force.

MWCap will deliver greater lethality, protected mobility and endurance than Lighter Forces, without the deployment, logistic and support limitations of Heavy Forces.

It is important to understand that despite many claiming FRES was about delivering Brigades by air, it was not.

Throughout the four steps to achieve the Medium Weight Capability end state, air portability was at small scale.

The Medium Weight Capability would also provide manoeuvre support to armoured brigades and the whole would be delivered over four steps that included a whole raft of joint capabilities, C-17, BCIP, Watchkeeper and the Future Strategic Tanker Aircraft.

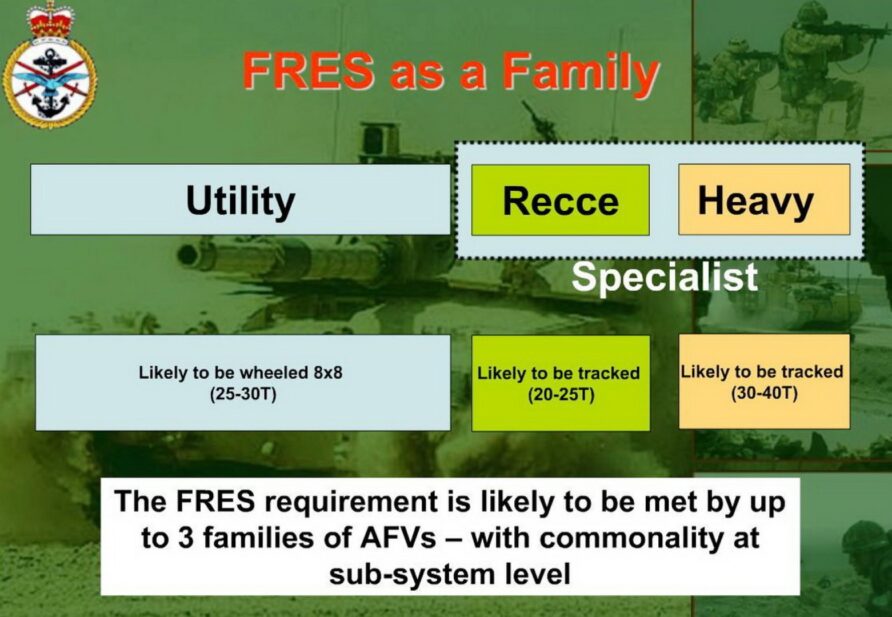

The FRES requirement was now likely to be met by up to three vehicle families with commonality at the subsystem level.

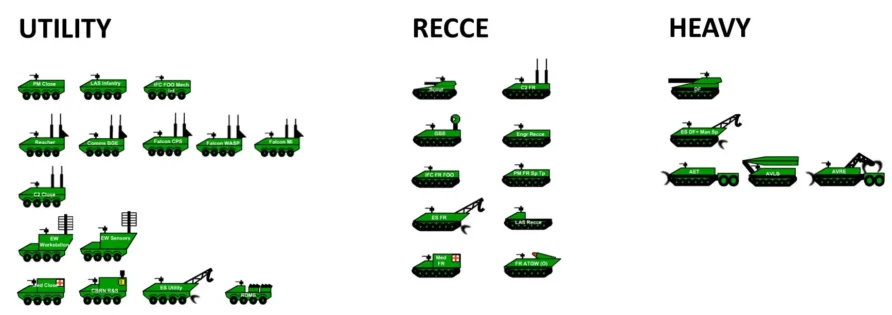

To deliver against the Medium Weight Capability, the FRES family was envisaged as three vehicle types:

- Utility; wheeled 8×8, 25 to 30 tonnes

- Specialist (Recce), tracked, 20 to 25 tonnes

- Specialist (Heavy), tracked, 30 to 40 tonnes

The air deployability requirement was A400M transport for the smaller variants at a range of 2,000nm and a target of carriage of the larger variants over the same distance.

The variants of roles for the FRES concept continued to evolve, but initial thinking was based on the following assumptions

Utility Variant

- Protect Mobility Close Support

- Command and Control Close Support

- Light Armoured Support Infantry

- Indirect Fire Control Forward Observation Officer Mechanised Infantry

- Falcon Wide Area Service Provision (WASP)

- Falcon Command Post Support (CPS)

- Falcon Management Installation (MI)

- Communication Reacher

- Communications Battle Group Enhanced

- Command and Control

- Electronic Warfare Sensor

- Electronic Warfare Workstation

- Medical Close Support

- CBRN Reconnaissance and Survey

- Equipment Support Utility

- Route Denial Mine System

Specialist Variant (Scout)

- Scout

- Ground-Based Surveillance

- Indirect Fire Control and Formation Reconnaissance Forward Observation Officer

- Equipment Support Formation Reconnaissance

- Formation Reconnaissance Medical

- Formation Reconnaissance ATGW (Overwatch)

- Formation Reconnaissance Command and Control

- Engineer Reconnaissance

- Protected Mobility Formation Reconnaissance Support Troop

- Formation Reconnaissance Light Armoured Support (Cargo)

Specialist Variant (Heavy)

- Direct Fire

- Equipment Support Direct Fire Repair and Recovery

- Manoeuvre Support Armoured Engineer Tractor

- Manoeuvre Support Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers

- Manoeuvre Support Armoured Vehicle Launched Bridgelayer

The total vehicle count was to be 3,775 over 16 roles, with an estimated price tag of £14.2 Billion.

Important to note that the Scout Variant, with a direct line to what would eventually become Ajax, was 20–25 tonnes, and the Utility Variant, also with a direct line to what would become MIV Boxer, was 25–30 tonnes.

Both were to be transportable by A400M to a range of 2,000nm.

On the 21st of June 2006, the Defence Main Board received presentations on FRES and the Medium Weight Capability called System and Programme Review 1

This was set against a background of increasingly political environment related to protected mobility vehicles in Iraq.

In July 2006, the FRES Draft System Requirement Document was released for comment.

At Eurosatory in July 2006, BAE showcased SEP, progress was being made on the three 6×6 wheeled and one tracked test rigs with additional FRES funding as part of the Chassis Technology Demonstrator Programme.

Writing in a RUSI paper, a Frost and Sullivan analyst argued that the FRES increase in ‘weight’ to increase protection was incorrect and instead, information superiority would provide greater protection.

The US-derived idea that ‘heavier is better’ for stabilisation missions is based on a false premise: it is not that heavier forces are indispensable, but rather that adaptable armour kits and better ISTAR capability to locate and track the enemy will allow for lighter, more easily deployable and adaptable systems without significantly raising the risk profile of a deployed force. Leveraging such information superiority will provide greater force protection as battlefield commanders will be better positioned to dictate terms of engagement to opposing forces, mitigating the effects of lighter armour configurations. This reinforces the view that MoD should look to developing its communications and new ISTAR concept instead of investing in costly bespoke AFVs in the 25–30 tonne range

A counterargument from Atkins, perhaps unsurprisingly, reinforced the prevailing view from the MoD.

The programme to procure and deliver FRES is about ‘the art of the possible’ and ‘coherence at pace’. There is now real and demonstrable momentum behind this critical programme. The UK MoD is investing today in driving a challenging FRES programme of emerging technology that will give the Army the operational edge needed to confront tomorrow’s threat – ultimately, our servicemen and women deserve no less

General Dynamics opened a FRES UK Joint Programme Office in September 2006.

LONDON, United Kingdom – General Dynamics United Kingdom Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of General Dynamics (NYSE: GD), has unveiled a dedicated Joint Programme Office supporting the British Army’s Future Rapid Effect System (FRES). The facility was officially opened by David Gould, the Deputy Chief Executive of the Defence Procurement Agency, in Bristol on 11 September 2006.

BAE completed work on its Systems Integration Laboratories at Leicester by September for 3D visualisation, Combat and Electronics

November 2006 saw another big FRES announcement and further information from the National Audit Office.

The System and Programme Review 2 was held, with alignment on the end of the TDPs to July 2007.

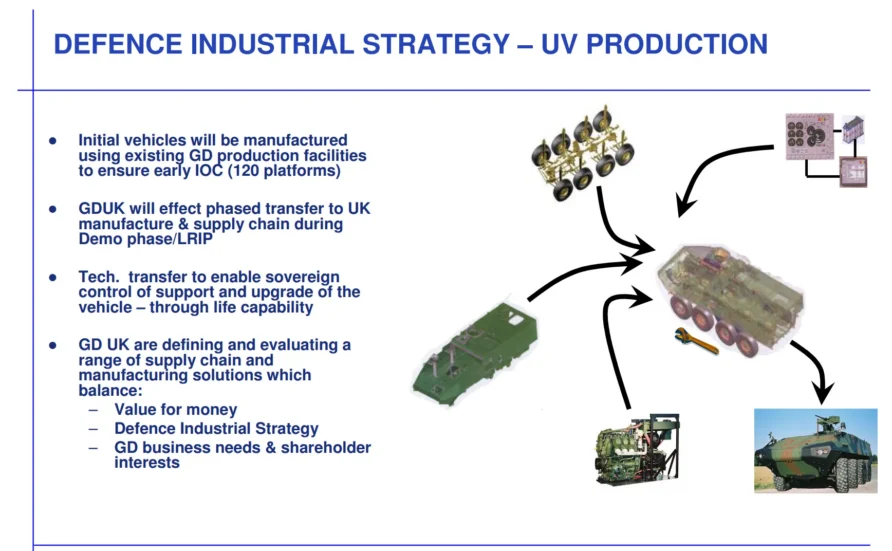

The acquisition strategy for FRES would be built around three tiers, a Systems of Systems Integrator, Platform Designer, and a Vehicle Integrator or Manufacturer, each one being subject to open competition.

The current planning assumption is to deliver 3,775 vehicles. The original requirement was for 1,757 vehicles but this was increased in 2004 under an equipment programme option when the Total Fleet Requirement had been established

When questioned by the House of Commons Defence Select Committee in December 2006, Sir Peter Spencer responded to a question about the value of TRACER and MRAV;

Because the project teams that were available at Abbey Wood would have drawn on the documents and the information which was learned from that work and used it as part of the foundation evidence as they built up their fund of knowledge as to what the requirement was and what sort of technologies were going to be needed to meet it.

In the MoD’s official response to the select committee owned up, FRES drew little from MRAV and TRACER.

At this stage, specific pull-through from TRACER and MRAV has been limited

Prophetically, it also included this statement

Lessons have been learned

BAE Systems TDP for chassis concept and gap crossing commenced in January 2007.

In January 2007, BAE showcased their 8×8 version of SEP, the vehicle that would be used for their chassis TDP.

The vehicle has a conventional mechanical driveline but used two diesel engines in the left and right sponsons to provide direct drive to the wheels.

This arrangement allowed the driver and commander to sit side by side and provided 13 m³ for the payload.

Also at the start of the year, a number of companies were preparing to respond to the FRES System of systems integrator (SOSI) requirement

- BAE

- Boeing

- Lockheed Martin

- SAIC

- Thales

The contract request for the Utility Vehicle integrator was issued in January 2007 with both the System of systems integrator (SOSI) and vehicle designer contracts planned to be awarded later in the year.

Jane’s reported on the acquisition strategy;

These competitions will result in the selection of one or more UV designs and one or two UV integrators. These selections will inform the generation of one or two UV Provider Teams to bid for the UV Demonstration Phase. There will not be a separate manufacturer competition for the UV programme. The winning party of the UV integrator competition will lead the provider teams and generate “robust” propositions for the demonstration phase while the winning UV designs will conduct ‘trials of truth’ due to take place by the end of the second quarter of 2007.

It was envisaged that the initial order would comprise 120 vehicles, with a total of 2,000 vehicles required in total.

Focus was very much on the Utility Variant (UV)

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) awarded a three year £9.48 million research contract to a QinetiQ led consortium for the Vehicle Technology Integration and Demonstrator (VTID) programme. Other members included BAE, Thales, Ultra Electronics, SciSys, SVGC, Williams F1 and York and Sussex universities. VTID was designed to demonstrate a layered protection system for a test bed vehicle, a REME FV432, as it turned out.

VTID was in addition to the FRES Integrated Survivability Technology Demonstrator Programme (TDP) and Electric Armour TDP, awarded to Thales to Lockheed Martin respectively a few years earlier.

The aim was

To quantify and demonstrate the utility of integrated survivability (other than physical armour) in respect of mounted close combat platforms, to counter the perceived threats in a range of representative scenarios

The scope included;

- Integrated Survivability (IS) & Infrastructure Concepts

- Mission Modularity

- Modular Dependability

- Physical Integration of a range of technologies: LSA and Acoustic Sensors, LWR, RWS, Obscurants, etc

- Demonstration of IS concepts in different military scenarios

Jane’s reported the range of technologies likely to be considered;

Visual awareness and sensor suites, disrupters, interceptors, smoke deception systems, active camouflage and electric armour.

On the 6th of February 2007, the House of Commons Defence Select Committee released their report on FRES;

The Army’s requirement for armoured vehicles: the FRES programme

The report opened with.

Between 2001 and 2003 the MoD commissioned Alvis Vickers to carry out ‘concept work’ on a new programme: the Future Rapid Effect System (FRES). There appears to be little tangible output from this concept work which cost the MoD a combined total of £192 million.

It went on to say

A sorry story of indecision, changing requirements and delay

The report detailed much of the FRES background and this interesting statement from Lieutenant General Andrew Figgures CBE, Deputy Chief of Staff (Equipment Capability)

The impression that the Army’s current armoured vehicle fleet lacks sufficient capability for expeditionary operations was reinforced by General Figgures who told us that recent operational experience in Iraq and Afghanistan had demonstrated that the Army needs a medium force “in order that we can fight as we would wish to fight

General Figgures confirmed that Mastiff and Vector were not considered long-term solutions.

…are not armoured fighting vehicles, they are a means of conveying people from A to B [with reduced risk] so they would not do what we require from FRES. They would not be able to carry out offensive action in the way that we would anticipate.

The Chief of Defence Procurement, Sir Peter Spencer, was also emphatic that FRES and the Protected Mobility vehicles were very different

These UORs have not impacted on the budget for FRES, full stop.

The four key requirements for FRES were described as:

- Survivability: through the integration of “passive and active armour and other vehicle protection technologies”;

- Deployability: it must be able to be transported by an A400M;

- Networked enabled capability: it must incorporate Bowman and ISTAR and other advanced digital communication systems (both data and voice) to allow full integration of the vehicles into the wider military network; and

- Through-life upgrade potential: It must be capable of being developed and throughout its expected battlefield life of 30 years

Finally, it reconfirmed the Army’s stance that NO off the shelf vehicle available would meet the FRES requirement, for any variant. The main reason cited was upgradeability over the expected 30-year lifecycle of the vehicles, specifically, 10-15% additional weight growth. An interesting position given a) the age of the vehicles currently in service, b) none of them were specifically designed to be massively upgradeable and c) the difference between in service weights and current weights of the same vehicles.

There was hope that FRES would be a significant export success. Intellectual Property issues were of great concern and because of this, the MoD insisted that all IP would be retained by the UK.

There was a great deal of confusion over the In-Service Date, and it is here that the Systems House actually demonstrated the value of having some measure of independence from the MoD.

Atkins submitted evidence to the committee that was crystal clear, FRES could be in service by 2018, but the assertion by the Army and others that 2012 would be a more realistic date was not supported by evidence.

The Chief of Defence Procurement went on record as stating the committee should not be taking Atkins’s view at face value.

In evidence to the committee, the professional head of defence procurement did not know about the Alvis pre-assessment contract;

That predates my involvement. I have no recollection of an assessment phase contract being given to Alvis Vickers but I will certainly go away and look up the detail and if I am wrong I will send you a note

The defence committee was not impressed.

Q52 Mr Jones: Can I say, Sir Peter, I find it absolutely remarkable that you can come here today in charge of this programme and say that you did not know about a non-competitive contract let to Alvis Vickers. I know about it; industry knows well about it.

Sir Peter Spencer: You called it an assessment phase contract and I challenged the fact it was an assessment phase contract.

Q53 Mr Jones: That is changing it. Are you aware of any non-competitive work given to Alvis Vickers in 2002?

Sir Peter Spencer: I am aware there was non-competitive work done before the initial gate.

Q54 Mr Jones: What was that?

Sir Peter Spencer: It was simply pre initial gate phase work.

Q55 Mr Jones: What was involved in that?

Sir Peter Spencer: To set out what the options would be.

Q56 Mr Jones: A minute ago you told us you did not know about it. Now you are trying to describe what went on.

Sir Peter Spencer: I am sorry, I do not mean to be pedantic but you asked me about an assessment phase contract; it was not an assessment phase contract.

Q57 Mr Hancock: What was it then?

Sir Peter Spencer: For the third time, it was a pre initial gate concept phase contract.

Q58 Mr Hancock: What did you get out of that?

Sir Peter Spencer: You get a broad understanding as to the sort of capability, the sort of aspirations that the customer has, the sort of technology which needs to be matured in order to move towards a solution. It is a perfectly normal part of the cycle. It is unexceptional.

Q59 Mr Jones: Sir Peter, that is not true, I am sorry. If you are sitting here today and telling us that that was just part of this entire process, that is not the case. Alvis Vickers were livid when you severed that contract because they were under the impression that FRES was going to be a non-competitive process and that work was part of what they thought was the start of the actual process. I understand and they can supply the information to us if you want that something like £14 to £20 million was spent in that phase. What happened to that work? It is no good coming here trying to wriggle out of it and say to this Committee firstly that you did not know what was going on and the next thing trying to explain what went on.

Sir Peter Spencer: Chairman, do I have to be on the receiving end of quite so much provocation? We could have quite a sensible and illuminating discussion.