Projects and programmes before Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance Tracked CVR(T) were somewhat complex and convoluted and it has taken me a few years and one or two errors to get the full story.

The 1957 White Paper had introduced radical force reductions and changes in strategy, and one of those was a UK based strategic reserve equipped for rapid air transport. This cascaded through the various departments until by the early sixties, a set of more formal vehicle projects were started.

CVR(T) Early Development History (1960 to 1968) #

The British Army and the Defence Policy Research Committee started work on a concept of reconnaissance operations to replace Ferret and Saladin, with a number of linked and parallel projects eventually producing the Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance family of wheeled and tracked vehicles.

The vehicles would be defined by high levels of strategic and tactical mobility. The question of wheels or tracks was left open.

In 1961, the General Staff Operational Requirement (GSOR) 1006, Air Portable Armoured Fighting Vehicle (APAFV), and the General Staff Operational Requirement (GSOR) 1010, Air Portable and Armoured Fighting and Reconnaissance Vehicle (AAFRV) were issued.

A number of different concepts and designs were considered, both tracked and wheeled.

GSOR 1006 vehicles were intended to be heavily armed and provide support to the lighter-armed GSR 1010 reconnaissance vehicles.

Early GSOR 1006 proposal eschewed the combined gun/missile launcher being developed for the US Armoured Reconnaissance/Airborne Assault Vehicle (M551 Sheridan) and proposed, instead, a mix of tracked and wheeled vehicles that would be no heavier than 15 tons and fit inside a Blackburn Beverley transport aircraft.

Initial concepts included a pair of casemated 105mm gun designs, also with Swingfire ATGW missiles, and two versions of the FV430 series equipped with a high capacity Swingfire launcher configuration.

These were joined by a more conventional designs, each with a fully traversing turret and 105mm main gun.

Finally, for the tracked concepts, (and I presented this in error in an earlier version of some of this content), a design with a forward mounted turret. Thanks to Armoured Archives in YouTube for spotting this and providing a correction.

Although not proposed for the GSOR, a 20-tonne test vehicle called the TV1000 (powered by a Rover Meteorite V8 petrol engine rated at 535 bhp) introduced a number of concepts might have appeared in the final design.

The ‘skid steering system’ of the TV1000 (it was actually much more sophisticated than that) caused many problems: tire wear, poor stability at speed and poor turning performance on soft ground.

GSOR 1006 also included two 6×6 wheeled designs.

A review of the two projects concluded it would be wasteful to pursue both and so they were merged, initially retaining the GSOR 1010 name. It was also thought they were becoming too heavy for air transport.

In 1963, the Defence Policy Research Committee was succeeded by the Defence Research Committee and Director Royal Armoured Corps, formed General Staff Operational Requirement (GSOR) 3301 in 1964.

GSOR 3301 was renamed to Armoured Vehicle Reconnaissance (AVR) in 1964, again, wheeled and tracked, replacing Saladin and Ferret.

AVR was specified in four variants.

- AVR Fire Support (AVR/FS) to replace Saladin, but still armed with its 76mm main gun.

- AVR Anti-tank (AVR/AT) is an anti-tank guided weapon launcher, Swingfire.

- AVR Anti-APC (AVR A/APC), armed with a medium calibre automatic cannon for destroying enemy APC and recce vehicles.

- Liaison Vehicle, to replace Ferret.

An APC, recovery, ambulance and command vehicle would also be required.

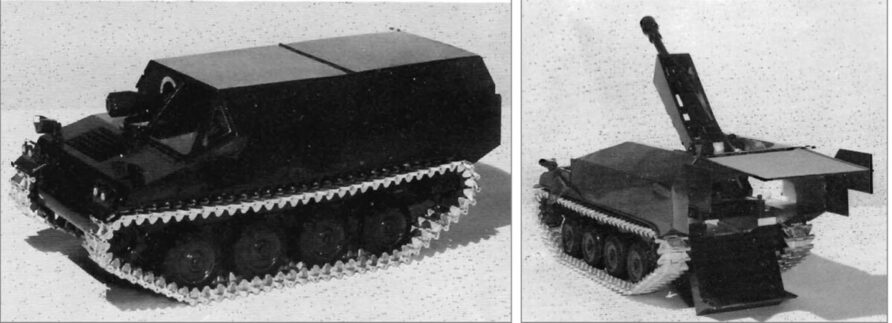

In parallel, FVRDE was working on a lightweight self-propelled carrier for a new 105mm howitzer Lightweight Close Support Weapon System, which was to replace the 105mm Pack Howitzer.

This was to be constrained by the payload capacity and internal dimensions of the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy transport aircraft. The Argosy’s payload capacity was very low by today’s standards, at just 4.5 tonnes, and was withdrawn from RAF service in 1975.

The vehicle design provided for recoil loads to be transmitted to the ground via an extending spade. The driver and three crew were provided only with minimum protection and there was a proposal to allow the gun could be demounted, so the vehicle could then be used for moving ammunition from landing sites.

Although ultimately rejected by the Royal Artillery, the chassis would form the basis for the Lightweight High Mobility Tracked Vehicle (LHMTV) concept study. This retained the 4.5 ton upper limit so that three could be carried in RAF Argosy an and even specified an helicopter transportable limit of 3.6 tons.

This designs included an APC, a 120mm recoilless rifle carrier, an armoured ambulance, ATGW carrier, ambulance and a reconnaissance detachment carrier, concepts from 1964.

The images below are all labelled LHMTV in various older sources but I don’t know for sure if they are.

The larger version with an extra roadwheel was clearly going in the same direction of travel as CVR(T).

None of these designs were ever built.

GSOR 3301 then absorbed some smaller programmes, including the UK/Australian Lightweight High Mobility Tactical Vehicle (LHMTV) described above, and would eventually change to the Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance requirement.

The heavier AVR and ultra-lightweight LHMTV would meet somewhere in the middle for CVR(T), with 6.5 tons being a more realistic limit, although this was subsequently revised upward to 7.9 tonnes as more protection was specified.

The wheeled requirement had originally been dropped from AVR, but would now re-appear as Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (CVR).

- GSOR 3358 was wheeled, and would go to become CVR(W) Fox

- GSOR 3301, was tracked, and would go on to become the CVR(T) family of vehicles

In 1965, the Fighting Vehicles Research and Development Establishment (FVRDE) developed and built the Test Vehicle (TV) 15000 as a precursor to CVR(T), so as to test and de-risk some of the automotive designs.

TV 15000 featured a range of new innovations. Aluminium armour, for example, had never been used on a British vehicle, before. Its hydropneumatic suspension and lightweight tracks were also at the cutting edge.

Also in 1965, and in parallel with work by FVRDE, the UK, Australia, Canada, and the United States entered into an agreement to explore concepts for a common light vehicle called the Armoured Reconnaissance and Scout Vehicle. The initial design work was carried out by FMC in the USA with a tracked design

Lockheed Missiles and Space Company offered a wheeled design.

The UK, Australia and Canada withdrew from the project soon after the initial were developed in late 1965.

Meanwhile, work on TV15000 had continued and by the end of 1966, FVRDE had produced two new test rigs, one static and one mobile.

The Test Rigs were intended specifically to prove the automotive components: engine, transmission, track and suspension. The TN-15 transmission was a scaled-down variant of the Self Changing Gears Ltd Merritt Wilson TN12 as used in the Chieftain. This system was so far ahead of its time that the designer reputedly had a nervous breakdown trying to figure out how to design the final drives!

The original hydropneumatic suspension of the TV 15000 was eventually replaced with a more conventional torsion bar design and the Rolls Royce Vanden Plas B.60 engine was swapped for a new version of the 4.2 Litre Jaguar XK.

The petrol engine was de-rated to 195 bhp in order to allow it to use low octane fuel, and this produced a power-to-weight ratio of approximately 26 bhp/tonne, delivering a range of 600km.

A representative turret was soon added.

So, as can be seen from the above CVR(T) and CVR(W) were linked by a convoluted series of linked, separate, and parallel concept and design efforts, but they all culminated in late 1967.

September 1967, Alvis was awarded a contract to produce 17 CVR(T) prototypes from the Mobile Test Rig design and test studies, prototypes would include Scorpion, a version armed with the 30mm RARDEN cannon, recovery, command, APC, and Swingfire ATGW carrier.

CVR(T) Trials and Production (1969 to 1972) #

The first prototype Scorpion was rolled out of the Alvis factory on January 23rd 1969.

Before production got underway for CVR(T), an extensive trials programme was carried out by the Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment (MVEE) and Royal Armoured Corps (RAC) Equipment Trials Wing.

These trials took place in the UK, Australia, Abu Dhabi, Iran, and Canada.

Tests were conducted in dry and humid conditions, and between temperatures of -25°F (-32℃) to +125°F (+52°℃).

The British Aircraft Corporation stratosphere chamber at Weybridge in Surrey was used to determine power losses at (simulated) altitude. The tests demonstrated highly impressive reliability, mobility, gunnery and maintainability.

After formal acceptance into service, Alvis was awarded a production contract in May 1970 and the Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (Wheeled) CVR(W) Fox production contract awarded to the Royal Ordnance Factory (ROF) Leeds.

The production variants were.

- FV101 COMBAT VEH RECONNAISSANCE FULL TRACKED 76MM GUN

- FV102 COMBAT VEH RECONNAISSANCE FULL TRACKED GUIDED WEAPON STRIKER

- FV103 COMBAT VEH RECONNAISSANCE FULL TRACKED PERSONNEL SPARTAN

- FV104 COMBAT VEH AMB FULL TRACKED SAMARITAN

- FV105 COMBAT VEH RECONNAISSANCE FULL TRACKED SULTAN COMMAND

- FV106 COMBAT VEH RECONNAISSANCE FULL TRACKED SAMSON RECOVERY

- FV107 COMBAT VEH RECONNAISSANCE FULL TRACKED SCIMITAR

FVRDE (Fighting Vehicles Research and Development Establishment) and MEXE (Military Engineering Experimental Establishment) merged in 1970, renamed to the Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment (MVEE).

Belgium placed an export order for 701 CVR(T) in 1970.

The first pro-duction Scorpion was completed in 1971 and first deliveries to the British Army began in January 1972 to the Armour Centre at Bovington in Dorset, and the School of Electrical and Mechanical Engineering at Bordon in Hampshire.

CVR(T) Service History (1973 to 1982) #

By 1973, Scorpion had entered service with the British Army, specifically the Blues and Royals in Windsor and 17th/21st Lancers in West Germany.

During the initial deployments in Germany, a Scorpion also set the record for a tracked vehicle around the Nürburgring.

The mobility improvements over Saladin were significant.

We did an exercise early on called “Lobster Quadrille”, where our aim was to infiltrate behind the enemy. We achieved it by driving up a river bed at night, a route the enemy had not anticipated anybody using. You could motor along at very low revs making it very difficult for anyone to hear you, or to place you if they could hear the engine.

CVR(T) entered service with Belgium in 1973.

Scorpions from A Squadron 16th/5th The Queen’s Royal Lancers were transported by RAF C-130 Hercules aircraft to Cyprus in August 1974.

They were to protect the British Sovereign Base Areas during the Turkish invasion of the island.

In 1976, a series of modifications and upgrades to the CVR(T) vehicle fleet, designated as Operation Bargepole, commenced at the Alvis works in Coventry. This programme addressed issues that had been identified with the gunner’s sight and the gearbox.

A number of Scorpions were also airlifted to Belize in 1977 to quickly reinforce the garrison after border tensions rose.

A trip to Heathrow in response to a security alert.

Early use had shown that some of the aluminium alloy armour was susceptible to stress corrosion cracking. This issue was particularly pronounced in the gun mantlet of the Scimitar variant, although it affected all CVR(T) vehicles to varying degrees.

Research conducted at the Military Vehicles and Engineering Establishment (MVEE) at Chertsey led to the initiation of Operation Scorepole in 1978, which involved replacing the cracked armour with a new alloy conforming to the MVEE 1318B standard.

The MoD confirmed in 1997 it would install a thermal observation and sight system in Scimitar vehicles.

The Republic of Ireland ordered a small number of Scorpions in 1980.

Alvis revealed a diesel engined Scorpion was available for export, equiped with a Perkins T6 3544.

Six RAF Regiment Field Squadrons received CVR(T) from 1981, after orders were placed in 1979. New Zealand likewise.

CVR(T) and the Falkland Islands Conflict (1982) #

CVR(T)’s operational service in the seventies had demonstrated the vehicle’s exceptional mobility and ease of deployment. This meant it was to find a role in the Falklands Conflict in 1982, although many doubted it could cope with the terrain.

On the 4th of April 1982, two troops (3 and 4) from B Squadron The Blues and Royals and a Samson Recovery Team were tasked to travel south. Their vehicles were actually in containers at Southampton on their way Salisbury Plain for a forthcoming training exercise.

After retrieval, the Troop’s started preparation and drawing stores a recommendation that a HQ element should also embark were rejected by the task force planning team.

On the 6th of April, vehicles were embarked aboard the M/V Elk while crews embarked on the SS Canberra. The vehicles taken were Scimitar, Scorpion and a single Samson.

After arriving at Ascension Island and engaging in some range practice the vehicles were then moved aboard HMS Fearless in readiness for the amphibious landing at San Carlos.

3 Troop were planned to be attached to 40 CDO at San Carlos and 4 Troop attached to 3 PARA and at Port San Carlos in the north.

After the initial landing had taken place the lodgement area was first enlarged in preparation for the move on Stanley.

During this time the Scorpions and Scimitars provided perimeter security from dug-in positions prepared by Royal Engineers Combat Engineer Tractor (CET) and acted as logistics carriers, shuttling stores from one place to another.

Even at this stage, many thought the terrain would defeat the CVR’s and that the vehicles would play little part in the continuing operations. But after some lobbying by The Blues and Royals officers they were tasked to support 45 Commando in their movement along the northern route, and 3 Para in their move to Teal Inlet.

2 Para, with their objective of Goose Green, were unsupported. It might be interesting to speculate on the effects armoured fire support would have had on the battle at Goose Green.

Lieutenant Colonel Andrew Jones (RTR) continues the story…

Battles fought across the high ground above Port Stanley were planned to take place at night and involved close direct and indirect fire support. The first phase-attack was opened by 3 Para with their assault on Mount Longdon. Initial surprise was achieved in the darkness, but the enemy was soon alert and resisted fiercely with heavy accurate fire.

4 Troop provided valuable direct fire support with their 76mm, firing HESH. The battle for the eastern sector of Mount Longdon was to last 6 hours and, for the western half, 4 hours. The enemy positions were captured by a process of calling for very close fire support, at times within 50 meters of the leading British troops.

Two techniques used by the British employing the CVRs proved very successful. The first involved a diversionary attack on the night of 12 June. In the attack, the Scots Guards employed 4 Troop in a reconnaissance role and then a direct fire role in support of the diversionary assault.

The impact of the use of the CVRs was instrumental deceiving the enemy.

The Argentine commander later admitted that “…he had been entirely deceived by the diversionary attack into thinking it was the main attack on his position”

The other technique employed by the CVRs is known as “zapping”: …the CVR crew would engage the Argentine position with a brief burst of machine gun fire provoking a response, which was promptly silenced by the main gun. The 30mm RARDEN cannon, with its high velocity and great accuracy, was much favoured for this technique.

Few Argentines felt able to reply after being zapped.

Light armour, played key roles during the Falklands War performing reconnaissance, security, and support of dismounted manoeuvre missions.

The presence of the CVRs during the initial build-up phase provided a degree of security otherwise not available had an attack been launched by the Argentineans, particularly if they had used their 90-mm gun equipped Panhard wheeled armoured vehicles.

Once again, armoured vehicles surprised their supporters and silenced the critics with their great mobility in terrain considered unacceptable. When employed in support of infantry, the CVRs provided critical direct fire, especially with their passive sights during the hours of darkness.

Additional roles of air defence and aiding the logistics only enhanced the primary fire support role provided by the CVRs.

The two troops deployed provided fire support for the 2nd Battalion The Parachute Regiment during the Battle of Wireless Ridge and for 2nd Battalion Scots Guards during the Battle of Mount Tumbledown.

CVR(T) was well suited to the boggy terrain of the Falklands because of its very low ground pressure, a point it proved many times, more often than not to the surprise of locals and Royal Marines, who thought their Snow Cats were the epitome of poor terrain mobility.

Coupled with skilled driving, kinetic energy recovery ropes and the occasional assistance from the Samson of B Squadron meant that all fears surrounding their mobility were allayed.

An example of this was the point at which both Troops were ordered to Fitzroy to support 5 Infantry Brigade, a journey that was thought would take 48 hours.

In fact, it took six.

Meanwhile, the Argentine Panhard wheeled armoured cars stayed in Port Stanley because of mobility issues.

CVR(T) also proved resilient.

A Scimitar was damaged by a mine and was recovered by the sole Chinook in theatre, repaired by the attached REME section and returned to service in short order. The immediate vicinity of the mine strike was subsequently cleared of 57 mines of various types.

The sole Sampson recovery vehicle also tipped over the side of a small bridge but was also quickly returned to service.

Lieutenant Innes-Ker described the incident.

We set off for 2 PARA’S position and after about 4 miles we got to Murrell Bridge. I had been warned that we may be too heavy for it so I got out and tested it. I didn’t like it at all and wasn’t going to cross it, but Lance Corporal Mitchell assured me he could do it so off we went and by God, the bridge bent. It was being pushed to its limits and there was no way Two Eight [Samson] would be able to cross it, with its extra weight being about 2 tons heavier than us.

A damaged Scorpion from Falklands service was eventually rebuilt as a Sabre.

Shortly after, Alvis launched the Streaker High Mobility Load Carrier, a variant of the Spartan.

Oman ordered CVR(T) in late 1982.

Together with the British Army, MVEE conducted a study programme in 1983 called the Family of Light Armoured Vehicles (FLAV) that was intended to inform replacements for CVR(T), FV432, Fox and Ferret, Saxon and Saracen, and some B vehicles.

This marks the first point that CVR(T) replacement was being considered.

FLAV concluded in 1988, and although it was only a study, it matured into another programmed called the Future Family of Light Armoured Vehicles (FFLAV).

Future Family of Light Armoured Vehicles (FFLAV) started straight after, in 1988, with the goal of starting the procurement process in 1991.

Venezuela ordered 90mm gun equipped CVR(T) in 1988.

CVR(T) and The Gulf War (1990 to 1991) #

The 16th/5th The Queen’s Royal Lancers served as the formation reconnaissance regiment for the 1st Armoured Division, supporting the 7th and 4th armoured brigades.

During preparations for the 1991 Gulf War (Operation Granby), it was recognised that the conventional tactics for close reconnaissance that had been developed for use in Europe were less suited to the wide-open desert.

Units were reorganised into task-specific groups. In this case, a Recce Group now consisted of eight Scimitars, four Spartan Milan Compact Turret vehicles, one Samson and a Forward Observation Officer Warrior.

The 16/5 The Queen’s Royal Lancers, based in Germany, was mobilised in December 1990 and deployed to Saudi Arabia in early January 1991, with vehicles transported by roll-on/roll-off ships and integrated into the 1st Armoured Division.

They were joined by The Queens Dragoons Guards, and a selection of other CVR(T) users.

Training and acclimatisation occurred in the Saudi desert, with CVR(T) units conducting exercises to adapt to the terrain. By mid-January 1991, the division was positioned near the Iraq-Saudi border as part of US VII Corps, ready for the ground offensive.

CVR(T) vehicles saw action during the ground phase of Operation Desert Sabre (24-28 February 1991), primarily in reconnaissance and flanking roles as the 1st Armoured Division advanced into Iraq.

At this point CVR(T) was over 20 years old and, although there had been some incremental improvements, the basic design was beginning to show its age, especially in comparison with newer vehicles.

The optronics were noted as being particularly poor for the conditions encountered during operations in Iraq.

Improvements were needed, badly, although as in many cases, deployability was excellent.

CVR(T) and Operations in the Balkans (1992 to 2002) #

Scorpion was taken out of service in 1992 due to concerns about the 76mm gun filling the turret with toxic smoke, an April 1992 MoD press release stating;

A study into the problems associated with propellant gases in the turrets of some older AFVs has alerted us to the potentially harmful effects of the build-up of residual gases during periods of sustained firing. In the interests of soldiers’ health, a ban has been placed on the firing of 76mm and CVR mounted 7.62mm machine guns and restrictions have been placed on the firing of others, except for operational emergencies.

The purchase of Chain Guns to replace 7.62mm GPMGs, the removal from service of 76mm guns and the Light A Vehicle Rationalisation Programme will address this problem in the long term.

Planning is in progress to address the immediate implications of this firing restriction

In 1992, Staff Target (Land) 4061 was issued, more commonly known as TRACER, Tactical Reconnaissance Armoured Combat Equipment Requirement, that was to be the CVR(T) replacement, flowing out of the earlier FFLAV work.

Following the violent dissolution of Yugoslavia in the early nineties, the first deployment of the British Army to the Balkans was in 1992 as a result of UN Resolution 743, the so-called Vance Owen Plan. 743 called for the creation of buffer zones between Serb and Croat forces in Bosnia and Croatia, the zones to be monitored by UNPROFOR.

UK forces were deployed under Operation Graple, from 1992 to 1995. Units included the 1st Battalion, Cheshire Regiment (initial battlegroup, armoured infantry with Warrior vehicles); rotations featured 1st Battalion, Devonshire and Dorset Regiment (1993), 1st Battalion, Royal Anglian Regiment (1993-1994), and armoured elements from the Queen’s Dragoon Guards and Queen’s Royal Lancers

Escorting UNHCR aid convoys started in 1993. Because BRITFOR was armoured and had a certain reputation, success with aid convoys was better than many other nations, The combination of the imposing presence and protection of Warrior and the agility and mobility of CVR(T) combined to form an effective capability.

The relatively innocuous appearance of CVR(T) Spartan compared with Warrior was also exploited several times for transporting personnel when negotiating passage between different factions.

In March 1994, the Government decided to reinforce BRITFOR:

D Squadron The Light Dragoons were tasked to deploy under the command of 1 DWR to form BRITBAT 2

The deployability of CVR(T) was demonstrated again, a full Armoured Recce Squadron was driven from Hohne to Hannover, flown to Split by C130 and was on operations in northern Bosnia less than 7 days after being warned for deployment.

Four months later the Light Dragoons RHQ were tasked to deploy and in a similar scenario to that above they were flown out of Hannover and took command in the Maglaj ‘finger’ just eight days later.

Indonesia ordered Scorpion 90 and Storme rin 1995, with a second contract in 1996.

In order to enable CVR(T) to continue on until TRACER came into service, a Life Extension Programme (LEP)was initiated in 1995.

The LEP had three main elements.

- Rplacement of the all Jaguar petrol engines with a diesel engine and upgraded TN15E transmission.

- Installation of additional secure radio equipment and a thermal imaging sight that, unlike the installed OTIS, would allow use on the move.

- Several minor improvements which were to include fitting a GPS, a new 30mm APDS round and replacement of some of the electrical systems.

In addition, the Alvis Sabre entered British Army service in 1995, primarily equipping formation reconnaissance regiments. Sabre was a hybrid platform combining the hull of the FV101 Scorpion with the turret from the FV721 Fox armoured car.

The Sabre conversion work was completed by ABRO Donnington using parts supplied by Alvis.

In a separate development to the Life Extension Programme (LEP), during 1997 the MoD announced that 170 CVR(T) Scimitars would receive an upgraded thermal imaging system for both observation and gun sighting.

The candidate chosen was the Avimo Sight Periscopic Infrared Equipment (SPIRE). However, the full 170 vehicle aspiration was subsequently reduced to just over 100 and the later batches were to carry the prefix Enhanced or E-SPIRE.

A number of additional Scimitars were also fitted with the SPIRE system under an Urgent Operational Requirement for service in Bosnia as part of SFOR.

As part of the SPIRE programme, 40 Scimitar were also fitted with a TacNav digital compass and navigation system from KVH.

After a competition between Perkins, Cummins and Steyr-Daimler-Puch, the Cummins 6BTA was selected and a £32m contract awarded to Alvis for the work.

Deliveries of the LEP CVR(T) commenced in 1998.

As a result of these many different upgrades, the homogeneous CVR(T) fleet began to fragment, with fleets within fleets becoming the norm.

Other operations in the Balkans included.

- Operation Hamden (1994-1995)

- Operation Resolute (1995-1996)

- Operation Lodestar/Palatine (1996-1999)

During 1998, conflict returned to the Balkans, specifically the Serbian region of Kosovo, a region not included within the Dayton Accords. Repression and violence soon followed. Following the Dayton Accords it was NATO, not the UN that would be responsible for implementation of the agreement and so IFOR was constituted, the Implementation Force.

Off came the white paint.

Operation AGRICOLA was the name given to the subsequent UK contribution to KFOR, from June 1999.

KFOR entered Kosovo on the 11th of June 1999, two days after the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 1244.

During these initial deployments, the ability to carry CVR(T) as a Chinook sling load was also exploited to great effect.

As the decade closed, the remaining CVR(T) vehicles were provided with a new single pin track design called the TR10 from William Cook Defence.

In 2001, after a competition between Avimo, Hunting Engineering and Thales, a £230m contract was awarded to Thales for the Battle Group Thermal Imaging (BGTI) programme for thermal imaging sighting systems on Warrior and Scimitar.

The contract was split into two groups.

- Group 1 was for Scimitar and Warrior Section and Command IFV’s, both thermal imaging and navigation. 350 were fitted to Warrior and 146 on Scimitar.

- Group 2, was for 100 Warrior Repair and Recovery variants and excluded the navigation elements.

One of the key requirements for BGTI was integration with BOWMAN and the ability to hand-off target information to Challenger 2.

The legacy fleet was having to be being maintained beyond its intended point because of the failure of two attempts to replace it.

TRACER was cancelled in April 2001, FRES would now replace CVR(T).

In March 2002, a CVR(T) Scorpion was clocked at 82.23 km/h (51.1mph) on the QinetiQ Chertsey test track.

It is in the Guiness World Records

CVR(T) and the Iraq War (2003) #

CVR(T) was used to reinforce security at Heathrow Airport, again, in February 2003.

In March, after a build-up period, CVR(T), FV432 and Warrior went to war in Iraq again, with 1(UK) Armoured Division.

Scimitars of C Squadron Queen’s Dragoon Guards were planned to support the amphibious landings and some were embarked on the USS Rushmore but after a beach recce confirmed the presence of mines this was aborted and the Scimitars were disembarked at Kuwait.

They would later support operations after driving in.

The Operation in Iraq – Lessons for the Future, issued by MOD in December 2003, made over 430 specific observations and recommendations, including.

5.5 Smaller reconnaissance vehicles in the Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (Tracked) fleet were also highly valued. The improved levels of ballistic protection fitted to these vehicles successfully reduced the risk from small arms and mines. Their utility in this operation reinforced the requirement for maximum mobility, whilst maintaining stealth in order to carry out successful reconnaissance missions. The increased armour protection improved the utility of this equipment in the light armour role. In the reconnaissance role these vehicles proved highly effective, with crews able to locate targets and coordinate air support to attack them.

One of the key lessons was:

The fleet of smaller reconnaissance vehicles provided a valuable capability that underscored the philosophy of reconnaissance using stealth

The MoD issued a tender for an improved protection system for CVR(T) in August 2005 that described a requirement for mine blast protection (MBP) and ballistic protection (BP), 128 vehicles would be fitted with MBP and 158 with BP.

This followed the earlier UOR for similar protection kits supplied by Permali.

The Sabre variant was withdrawn in 2004.

By October 2005, the total UK fleet of Scimitars consisted of 328 vehicles and the Spartan fleet stood at 478 vehicles.

CVR(T) and Afghanistan #

Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (Tracked) (CVR(T)) variants, primarily Scimitar, were deployed from 2006 (Herrick 4) onwards.

The Daily Mail published a story in September 2007 that detailed the cooling modifications added to CVR(T) in Afghanistan.

A pipe to stick up their trousers

It was less than fulsome in its praise.

The Army Base Repair Organisation (ABRO) was awarded a contract in 2006 from the MoD for the Light Forces Tactical Mobility Platform (LFTMP) Capability Demonstrator.

The ABRO facility at Donnington, UK, has completed the Light Forces Tactical Mobility Platform (LFTMP) Capability Demonstrator (CD) vehicle for the British Army in record time. The LFTMP CD is essentially an Alvis Sabre reconnaissance vehicle with its two-person 30 mm turret removed. The rear of the vehicle has been modified and a drop-down door has been fitted to facilitate the rapid loading and unloading of equipment.

The vehicle, over the frontal arc, retains the standard level of protection from small-arms fire with the belly providing protection against some mines. The LFTMP CD will play a wide range of potential roles covering command, logistic and support functions. Commercial roles played by the vehicle could include communications as well as more specialist roles such as forward observation officer for artillery, and mortar fire control.

The vehicle will cover support functions that include carrying small-arms ammunition as well as more sophisticated weapons, such as 81 mm mortars.

Following experience in Afghanistan, the MoD embarked on an additional Environmental Mitigation programme for just over 100 CVR(T) vehicles in 2008.

FRES was cancelled in 2009, with the Specialist Vehicle (SV) requirement moving forward alone.

This would eventually go on to be Ajax.

At the end of February 2010, the Investment Approvals Board met to decide between General Dynamics and BAE for the FRES SV Recce Block 1 development contract.

Several outlets reported that General Dynamics had won the contract, although this was not to be confirmed by General Dynamics until March.

June 2010 also saw a number of media reports that BAE and the MoD were negotiating the restart of the CVR(T) production, at least for hulls.

DefenceIQ reported;

The UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) and BAE Systems are negotiating the re-started hull production for the British Army’s Combat Vehicle Reconnaissance (Tracked) (CVR(T)) fleet.

The heavy wear and tear, corrosion and fatigue on the CVR(T)s deployed in Afghanistan has prompted the move, which has raised concerns among British Army equipment managers that the fleet of CVR(T) derivatives could soon be rendered combat ineffective.

There are 1,100 CVR(T)s still in use. The CVR(T) is currently the mainstay of the Royal Armoured Corps’ reconnaissance regiments.

There are reportedly also concerns among senior army officers that the scout variant of the recently selected General Dynamics ASCOD Future Rapid Effect System (FRES) vehicle will not be ready by the planned 2015 in-service date to replace the CVR(T).

It is still not clear how many hulls are involved, but all the 100 or so vehicles deployed in Afghanistan are expected to pass through the rebuilding process.

Army sources indicate that they expect “a couple of hundred” CVR(T)s to remain in service beyond 2016 for use in air-portable and amphibious rapid-reaction units where the requirement is for a vehicle weighing less than 10 tonnes.

It was revealed later that CVR(T) Mark 2 would use new build hulls and a wide range of other improvements in almost every area under Project Transformer.

Scimitar Mk2 would also mate a Scimitar turret to a Spartan Mk2 hull. Pretty much every component was replaced or upgraded, mobility, protection, power provision and maintainability all improved.

The contract for 58 vehicles was awarded in December 2010.

The first batch was for 47 vehicles, and the second batch, 11. The first batch consisted of four Samaritans, nine Spartans, two Sultans, two Samsons and thirty Scimitars.

CVR(T) Mk2 deployed to Afghanistan in August 2011.

BFBS reported on the deployment.

In early May 2012, BAE released details of a light tracked vehicle built on the work completed as part of CVR(T) Mk2. CV21 had a top weight of 17 tonnes, armed with a turret mounted automatic cannon and was amphibious. With a target cost of £1m BAE soft launched the concept to gain interest. (more on this in the Stormer section of the Knowledge Base)

CVR(T) Mk2’s were fitted with rollover protection in early 2014.

Later in 2014, British forces ended the combat mission in Afghanistan, with some remaining under Operation Pitting until 2021.

Return to Contingency and Withdrawal #

In March 2016, the Latvian Army released images of Exercise Allied Spirit VI in which their CVR(T) vehicles obtained from the UK were used to great effect.

Under Operation Cabrit (since 2017), CVR(T) variants, including Scimitar, have been deployed with UK-led NATO battlegroups in Estonia and Poland as part of the Enhanced Forward Presence (eFP).

The CVR(T) Mk 2 fleet was withdrawn from active British Army service in 2023, as part of the broader phase-out of the entire CVR(T) family.

This left 97 FV107 Scimitar vehicles (including Mk 2 variants) and a total of 114 CVR(T) platforms in the disposal process by May 2024, with some donated to Ukraine (e.g., 23 Scimitar Mk 2 in 2023).

Ukraine Service #

Ukraine has been an enthisiastic recipient of CVR(T) from the UK and Latvia, including commercial disposals.

In September 2024, Latvia announced the transfer of an unspecified number of ex-British CVR(T) vehicles (primarily Scimitar) to Ukraine, following Latvia’s acquisition of 123 vehiles from the UK in 2021 for £39.5 million.

These have been upgraded and are used for reconnaissance and mobility support in Ukraine’s defence against Russian forces.

Mostly Spartan and the support variants, although they have regunned some Scimitar (including Mk2) with a 14.5 mm KPVT heavy machine gun as well.

Summary #

CVR(T) provided 51 years of service to the British Army, and wherever the Army went, CVR(T) went with it.

More than 4,500 vehicles were sold, to 23 nations.

Although it had a fairly convoluted genesis, the work done by Alvis, FVRDE/MVEE and the RAC combined to produce a unique vehicle family that endured multiple attempts to replace it.

Just over two thousand CVR(T) entered service with the British Armed Forces, and another one thousand five hundred for eighteen export customers.

It left service in 2023/24, replaced by Warrior and other wheeled vehicles in the interim, until Ajax enters service.

I will leave the last word to Dean, a Think Defence commenter.

I am now retired from the Army and embarking on my second career, but I spent most of my 22 years serving in CVR(T) and most of what has been written here has been discussed by the men that did crew them and still do!

It is a fantastic piece of equipment, years ahead of its time when designed and that very fact that there is literally nothing that can do what it does, on the market today, marks it as still being a unique and valued capability, that as was written in the article, we lose at our peril.

In the Falklands, it was 10 years old, relegated to secondary roles for fear it would not be able to traverse the terrain, well it did and in the post op reports, they wanted a Squadron, if not a Regiment down there.

In Granby it was written off again because “it wouldn’t keep up” with Challenger/Warrior. Well not only did it, but it was proved that both in the Close and Formation Recce role, the need for the manned platform to FIND the enemy, FIX him and if it went pear shaped could stand up for itself till the big boys arrived, was as valuable as ever and the platform of choice?

In the Balkans, during the winter of ’93-’94, the only vehicle that could move over roads with inches of black ice, offer protection against IDF and traverse the steep, snowy terrain to get the job done was CVR(T).

During Telic 1 it was engaging and holding its own in fights with T55 while its human crew made the decisions to use Arty, Air or other ground units to out manoeuvre the enemy.

On Herrick with Mine blast Protection, ballistic protection and bar armour, not only does it mean the crew walk away from mine strikes and RPG strikes, I’ve seen it first hand, but in some cases the vehicle not only survives, but continues to fight! (But the extra protection does push it to 11 tonnes!)

Why is CVR(T) so good at what it does?

It has the perfect balance of Armour/Protection/Firepower but it is its size and weight that means it can go anywhere and do anything.

I for one, along with many other will shed a tear when it finally backs into the hanger for the last time.

Quite.

If you found value in this article, help me keep Think Defence going.

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless. I have removed those annoying adverts, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up.

To help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

You can click on an affiliate link, Buy Me a Coffee at https://ko-fi.com/thinkdefence, download an e-book at https://payhip.com/thinkdefence or even get some TD merch at https://www.redbubble.com/people/source360/

Youtubers, if you are going to lift content from here, the decent thing to do would credit me