The more you read about the Haiti earthquake response, the more you realise what a magnificent, awe-inspiring effort it was.

Israeli and Iranian teams working side by side, the air, and sea logistics effort stretching every sinew to get supplies in, and medical assistance that saved numerous lives were straight out of the top drawer.

Nations from all over the world sent help.

Large and small businesses, NGOs, individuals, and governments were all involved.

The Royal Fleet Auxiliary and 17 Port and Maritime Regiment Royal Logistic Corps (those magnificent men and Mexeflote machines) also get an honourable mention.

The story is also one of individuals, some recognised, and many whose names and achievements are lost to time.

Junior NCO’s and officers had a disproportionate impact.

I hope this series of posts does them justice.

Haiti Earthquake Response General Observations

Lady luck and circumstance played their part in the responses to this tragic event.

Supply lines were short, many adjacent countries offered support (not least the Dominican Republic) and many responders were already in the area.

It is often said that the more one practices, the better one luck becomes. This was true for the main body of military forces involved in the response, many having completed large-scale exercises that practised many of the capabilities used only the year before.

Despite this, the sheer scale of the response and the number of participants created many command and control problems, as identified by the RAND Analysis of the military response to the earthquake.

Tensions between civilian and military organisations were frequently overblown by the media looking for a story, but they did exist.

The demand for tactical information at a strategic level absorbed a great deal of time for little benefit, the long-handled screwdriver as useless as ever, driving activity from adverse media coverage was a common problem

VIP visits and media personnel often absorbed precious resources that could have been better spent elsewhere.

At its peak, 22,000 US military personnel were engaged in Joint Task Force Haiti, each requiring food and water in a food and water-constrained environment.

The geography and time of year also ensured that sea conditions were benign, another place and another time may well have entirely changed the ability of responders to get so much ashore so quickly.

Information and reconnaissance assets were invaluable, but by Day 2, Google and others had made available high-resolution satellite imagery which would form the basis of several innovative mapping and survey applications and arrangements. All responders reporting it as having a very positive impact on the response.

Despite the local mobile telecommunications infrastructure being initially damaged, when re-established, the communication tool of choice was the Blackberry, being able to integrate civilian communication systems was a key lesson, as was the power of web services and SharePoint.

Joint Task Force — Port Opening (JTF-PO) were the real drivers of air and seaport opening, despite most having never heard of

Haitian companies, despite having to deal with their enormous problems, were not bystanders either.

Defence organisations tend to understand the limitations of their capability because they are a cohesive unit, civilian organisations might have never worked together and whilst they often have logistics capabilities far above defence, they might not understand collective capabilities.

Using defence capabilities for disaster response is always fraught with politics, in most cases, civilian response is more desirable.

But here is the dilemma, defence usually has a range of resources and capabilities at high readiness that are not replicated outside military organisation.

In some subsequent analyses, the US military was criticised for not listening and just charging in, their speed was impressive, but many argued that this speed was frequently misdirected.

Is that fair, I don’t know, it seems churlish to criticise?

With the benefit of the finest quality hindsight goggles, could things have been done any better?

Air Logistics

28 hours after the earthquake, a small team had air operations up and running at the airport, a feat for which they received well-deserved praise

From a normal 13 flight movements per day, they enabled an average of 120 movements per day for three weeks with a peak of 150 movements per day, without a single accident.

Let me repeat that, without a single accident.

However, it was argued that in failing to deploy a more suitably resourced team quickly enough, throughput from the airport did not realise its full capacity until much later.

The need for aircraft tugs, heavy lift forklifts, telehandlers, aircraft loaders and fuel trucks at the airport was well understood and stood on the critical path, but transport to Haiti had to compete with pallets of water and medical crews.

NGOs understandably want to get aid supplies in and medical evacuees out, but without the capacity enablers, going fast results in going slow.

This was a recurring theme, more speed, less haste.

The lack of a deployable ATC tower also made things more difficult than they should have, there were many solutions available that did not need a Russian AN-124 to move.

Delivering anything by helicopter is low capacity and inefficient, particularly for dense stores like water. Much was made in the media of the water generation capability of amphibious warships and carriers but getting it to the point of need was another matter.

Echoing more recent activities, using airdrops for humanitarian supplies was a double-edged sword.

Sea Logistics

The divers at the seaport operated in atrocious water conditions without appropriate protective equipment simply because none was available and the lack of joint training and equipment between the Army and Navy dive teams introduced unnecessary delays.

Divers took daily doses of antibiotics and were constantly monitored for health problems.

All for the lack of proper PPE, this is not how a responsible military meets the welfare requirements of its personnel, no matter how noble the cause.

The importance of material handling equipment (especially the Kalmar RTCH), clearing pathways out of a port area and the ability to move supplies out of port areas were again reinforced

Landing supplies is only half the issue, getting them to the point of need promptly is the other half.

Seemingly minor activities like building RORO ramps at Red Beach out of compacted earth and gravel were hugely impactful stores flow through the port, basic combat engineering.

The ISO container continued to prove it is much more efficient than break bulk. Moving half-empty containers is a fool’s errand.

Whilst the JLOTS piers and lighters were invaluable for moving plant and vehicles to shore, the amount of double handling required for palletised and containerised stores meant, in reality, it was quite inefficient. If it has wheels, JLOTS is excellent, if it doesn’t, there is a great deal of double and triple handling to be considered.

Despite how impressive JLOTS is, it is very labour-intensive.

The potential of the USNS Grasp was little understood, although she stayed the longest of any ship and offered invaluable salvage, survey, and diver support, she was initially characterised by SOUTHCOM as offering limited capability.

Survey and salvage are key enablers for port recovery.

The large Army and civilian landing craft provided greater utility than the USMC and USN would probably like to admit.

Although the smaller ports around Port-au-Prince were in some cases undamaged they were arguably underutilised in the response, some JLOTS personnel and equipment might have been better used for this. Indeed, some civilian response did make use of these smaller ports.

What is abundantly clear is that at scale’ there is no substitute for port facilities, going over the beach is great for the short term, but it simply cannot meet high-volume demand.

Military Sealift Command, The Maritime Transportation System Recovery Unit, the US Coast Guard, and Transport Command all deserved recognition.

But whilst many focus on the military and government response, one could reasonably argue that commercial organisations did the heavy lifting and received less credit than they should have.

It is easy to find lots of documentation about how the US Navy, Air Force or Coastguard performed, but information on the civilian response is fragmentary, tucked away in the Internet Archive, or unavailable.

Crowley Marine (especially), Titan Salvage, Foss, Seacor, ACTC, and Resolve Marine were notable examples at the seaport.

They were rolling quickly, often with only verbal agreements in place or none, Crowley even had a small float plane fly in a survey team on the 18th of January.

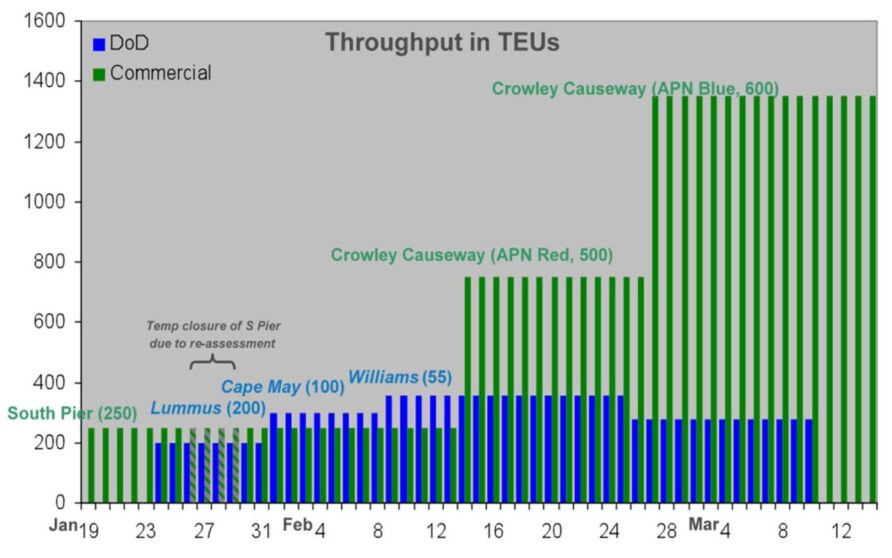

The step-change in throughput when the two barges arrived was noticeable (although the actual profile, in reality, would have been smoother); as soon as the second Crowley barge (APN BLUE) was in place, JLOTS was only used for military traffic.

The ‘Crowley Plan’ allowed the military to disengage.

Before the step change, the salvage effort took weeks of painstaking effort with cutting torches and cranes.

The first barge (APN RED) arrived on the 10th of February after salvage and debris removal commenced operations on the 13th of February, a month after the earthquake.

If the salvage operation had commenced earlier, the barges may have also been available sooner and the need for much of the JLOTS capability diminished. Perhaps even if some military capabilities had been applied to the debris removal, explosive cutting charges and heavy-lift helicopters, for example.

Heavy lift helicopters were certainly in the area, being used for aid supplies.

That a single cheap and simple barge with a crawler crane could deliver more than double the assembled military capability throughput is interesting.

Could APN BLUE have been in place quicker, perhaps not due to transit times, but it would be a fascinating ‘what if’ scenario to model.

The utility of such barges is a lesson from the 1982 Falklands Conflict and FIPASS that, seemingly, has been lost.

A Final Observation

In the final analysis, the effectiveness of the response was not about systems or equipment, it was about people, often, a few relatively junior or young people in key positions.

And that is the lesson that should never be forgotten, it is always about the people.

Sources and Document Information

Preliminary Reconnaissance Report – 12 January 2010 Haiti Earthquake: BFP Engineers

The MW 7.0 Haiti Earthquake of January 12, 2010: USGS/EERI Advance Reconnaissance Team Report

Operation Unified Response — Reconstruction and Analysis of the U.S. Navy Response

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_relief_efforts_after_the_2010_Haiti_earthquake

TRANSLOG – The Journal of Surface Deployment and Distribution Spring/Summer 2010

Analysis Of the United States Coast Guard’s Support In Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief Efforts

JTF Port Opening for Operation Unified Response

Air Mobility Command’s Response to the 2010 Haiti Earthquake Crisis

| Change Date | Change Record |

| 28/03/2017 | Initial issue |

| 23/07/2021 | Format refresh |

| 22/03/2024 | Complete re-issue |

The rest of the series

- Introduction

- Over the Shore Logistics in and around Port International de Port-au-Prince

- Air Operations and Toussaint L’Ouverture International Airport

- Observations

Read more (Affiliate Link)

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.