Despite the obvious utility of air operations for rapid response and time-sensitive materials, overland from the Dominican Republic and more directly over the beach or through the existing ports would have to be the main means by which the significant volume of relief supplies would be delivered.

Ports in Haiti

Although small in comparison to Port-au-Prince, there were other seaports in Haiti.

The main alternative to Port-au-Prince was Cap-Haïtien to the North, it too could handle mixed cargoes.

To the south, Jacmel was a small port with a single quay, but it too was severely damaged by the earthquake and its port would play a relatively minor role in receiving relief supplies.

Saint-Marc in the North West did have a small RORO berth, as did Petit-Goâve, Miragoane, Les Cayes, Port-de-Paix, and Gonaïves.

Labadie was mostly for cruise vessels and not equipped for extensive cargo handling.

The Haitian Coastguard port at Killick had a small pier, but this was severely damaged as well.

The main reasons they were not generally utilised beyond the provision of relief supplies for local populations were due to damage, small size, presence of derelict vessels, or for the most part, lack of good quality connecting roads to Port-au-Prince, where the vast majority of need was.

The area around Port-au-Prince would have to serve as the main conduit for inbound aid flows.

Haiti is not an island, it borders a large, and in comparison, a well-developed nation called the Dominican Republic. Much aid traffic did flow through the Dominican Republic, but again, the lack of roads meant this was less well utilised in the early stages of the response.

The centre of gravity for the international aid response was Port-au-Prince, and so would be its port.

Pre-Earthquake Seaports in Port-Au-Prince

The sea terminal at Port-au-Prince handled 95% of Haiti’s imports and exports of cargo and fuel.

The image below, taken in 1994, shows the port in use by US military vessels during Operation Uphold Democracy.

As can be seen, the area to the North of the North Pier had yet to be reclaimed and developed.

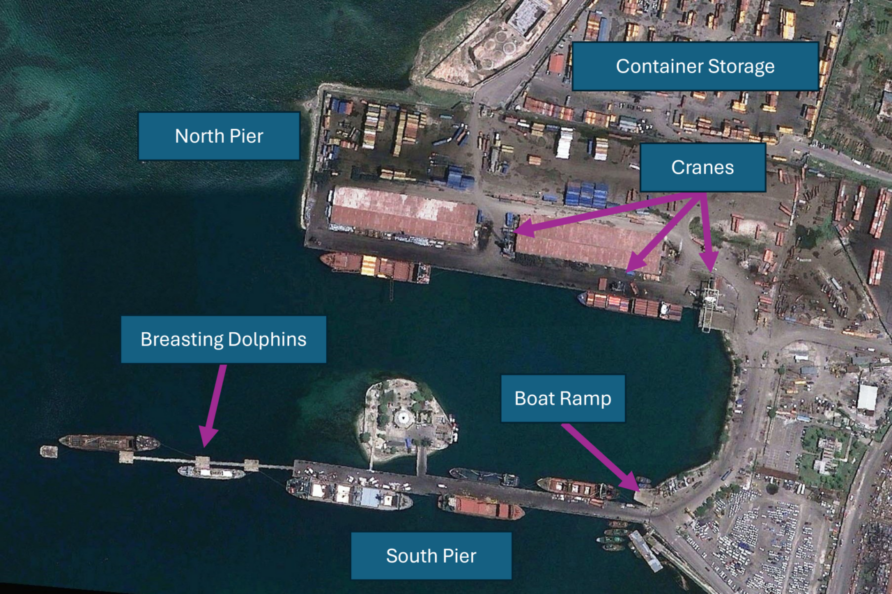

The image below shows the main port in 2008.

The French Bâtiment de Transport Léger (BATRAL) naval vessel Francis Garnier visited Haiti in the same period as the image above was taken.

Francis Garnier will make another appearance later.

Containers accounted for most cargo before the earthquake, with the North Pier handling approximately 230 TEUs daily.

The 450m long pier had a 15m Washington portal gantry crane and two Gottwald (now Kone) mobile harbour cranes. The pier also had several container handlers and warehouses, with a much larger container storage yard to the north. Many container vessels visiting the port also had ship-mounted cranes, as is common in the Caribbean.

The 380m long pier supported South Pier was used for break-bulk and RORO cargo, connected to Fort Islet Park, used by police and port security forces, and formerly a lighthouse.

Beyond the pier end were four breasting dolphins connected with narrow pedestrian walkways. A boat ramp and harbour tug mooring pontoon were also located at the South Pier.

At the north of the port extents was a ship-breaking yard.

2 km north of the main port was Terminal Varreux, the nation’s main fuel and vegetable oil terminal, with 18 storage tanks and a total capacity of 170 million litres.

The terminal accounted for 70% of all fuel imports.

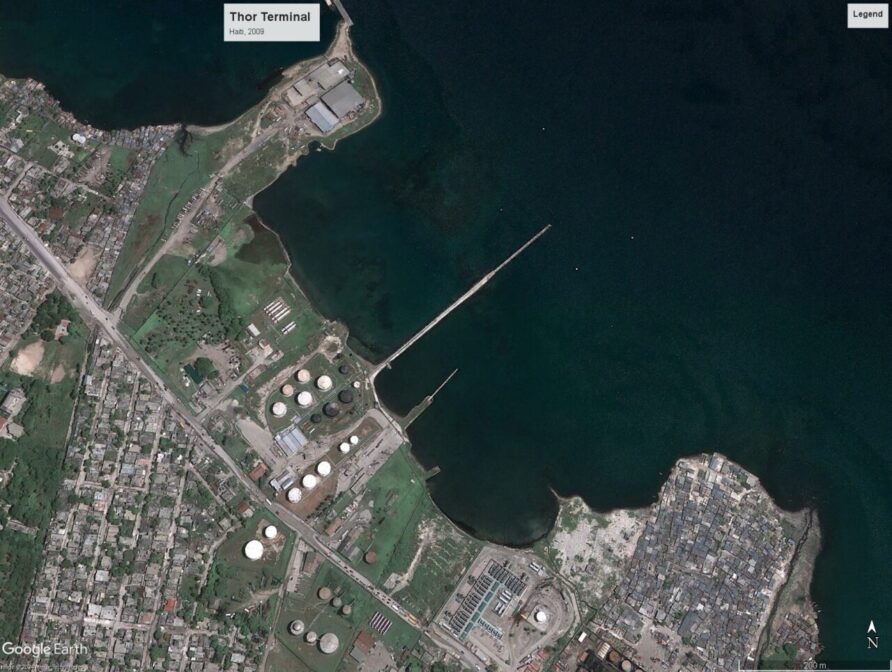

To the southwest of Port-au-Prince in Carrefour was a smaller oil terminal called Thor Terminal, served by a mixed pile/earth-supported jetty.

Earthquake Damage

Jaw-dropping images of the port emerged on the day following the earthquake.

The image sequence below was taken from a moored ship at the north pier, unloading containers, when the earthquake struck.

The two Gottwald harbour cranes are between the warehouses on the North Pier, one being used to load or unload the small feeder container ship at the top of the image and the other not in use. A dust cloud obscures some activity, but it is clear that the pier is laterally spreading.

In the foreground, a much larger ship with its bow pointing to the smaller ship is also loading or unloading two containers. Neither container makes use of spreaders. There appears to be a container handler at an angle and other containers are sinking into the liquified soil.

A slightly different view of the containers above.

The images below show the position of the harbour crane, the pier now being completely submerged, and the smaller vessel moving (quickly) away from the area.

The final images in the sequence show the smaller vessel out of the picture but the larger vessel, still moored to the submerged pier.

Quite incredible, I think you will agree!

I couldn’t locate any source that originally identified the two vessels, although the images were widely circulated, they appear to originate with a shipping forum user with the account name Duquesa in a January 14, 2010 post

Full credit to Duquesa for sharing the images.

The larger vessel appears to be the MV Michael J, now the Alianca del Plata (although there are others of a similar design)

Michael J also appears later in the story.

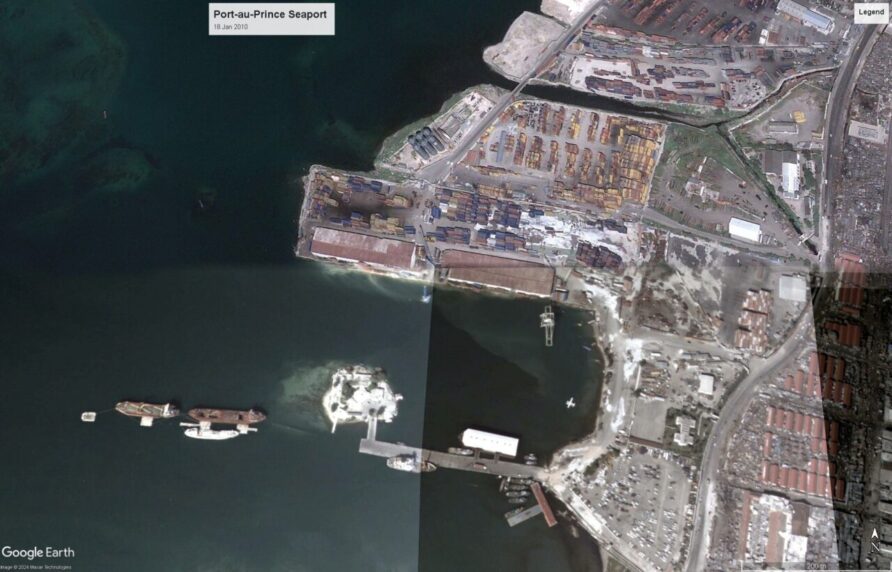

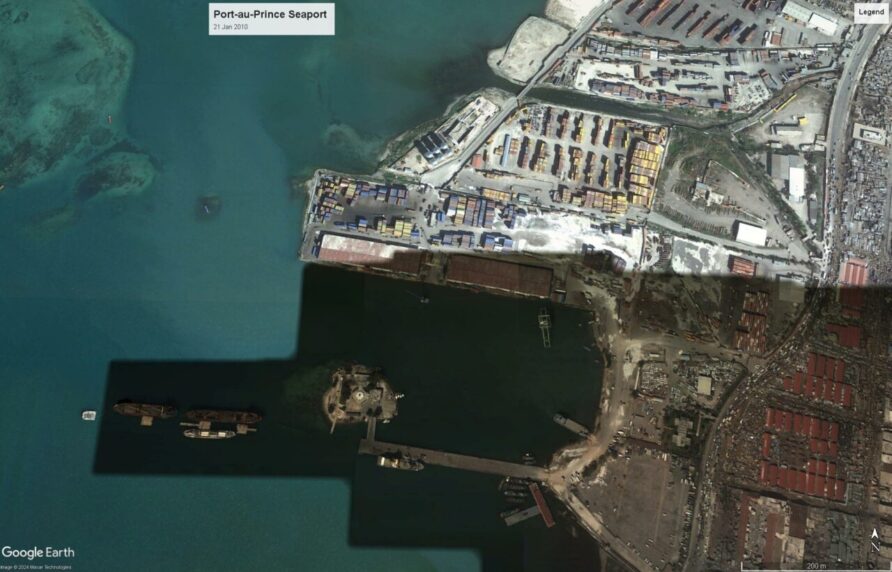

Images taken a day later show further the damage to the North Pier.

South Pier was also badly affected.

The 120 m-long western section of the pier collapsed and pedestrian walkways collapsed. 40% of the piles were broken and 45% damaged.

Three ships were moored at the dolphins during the earthquake, MV Nicholas, MV Hybur Star, and MV Gisela.

The access apron to the pier and surrounding roads suffered significant lateral spreading and displacement.

Although not in the port, electrical distribution equipment was also damaged or destroyed, so no power would be available for port operations, lighting for example.

The ship-breaker pier was destroyed.

At the Varreux terminal, a significant length of the pier collapsed, killing 30 men who were working on it at the time.

The Thor Terminal also suffered damage from lateral spreading.

Initial Response

On the same day as the earthquake, the US Ready Duty Amphibious Ready Group including USS Bataan, USS Carter Hall and USS Fort McHenry, were placed on 48 hours’ notice to move but the first assets to arrive were airborne.

The machinery of the US government and defence started almost immediately, various units were placed on standby, preparations made and people organised themselves in readiness for deployment.

On 12th January, the first overflight was completed by a US Navy P-3 Orion.

A US Coast Guard C-130 and a USAF OC-135 the day after.

Initial images confirmed that the port infrastructure had suffered significant damage.

Several hazards to navigation were observed, reefer containers with their foam insulation, for example, presented a dangerous floating hazard.

The US Coast Guard cutter Forward was the first vessel into port, arriving at 10:34 on Wednesday the 13th of January, providing air traffic control for the airport.

In Port-au-Prince, many piers had collapsed into the harbor and oil had spilled into the water, Commander Durham said, but there did not appear to be obstructions in the channel leading into the port, meaning that other American or foreign relief ships should be able to approach the area. For now, though, there is no easy way to land rescue supplies from ships, she said.

Washington Post

Forward also provided supplies and assistance to the local area.

The USCG cutter Fury arrived soon after.

Already in the area, USS Higgins, an Arleigh Burke destroyer, was diverted to Haiti, arriving off the coast of Haiti on the 14th of January as the first U.S. Navy ship on-scene, providing refuelling facilities for rescue helicopters.

By the end of the 14th, US Coastguard vessels off Port-au-Prince included the Forward, Mohawk, and Tahoma.

The USCG Cutter Valiant determined that Gonaïves and Cap-Haïtien could be used for barges or ships, the former with a 180-tonne crane and 10m draught pier.

The Joint Task Force – Port Opening (JTF-PO) Seaport of Debarkation (SPOD), specifically the 832nd Transportation Battalion based in Jacksonville, Florida, assembled a Joint Assessment Team (JAT) of fifteen personnel, ten commercial stevedores from Ambassador Services, and a contracting officer. The team had equipment to support operations, such as telehandlers and forklift trucks.

A 15th January 2010 report from CNN showed the extent of the damage to the South Pier

Interestingly, the UN Logistics Cluster recommended that Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic be used as the primary inbound cargo port with various NGOs reporting that whilst Cap-Haïtien was viable, the road conditions between it and Port-au-Prince would create significant cycle time delay, compounded by the shortage of trucks and drivers.

On the 17th of January, the USCG Cutter Oak arrived and after dropping off relief supplies at the South pier, embarked on her main task of establishing safe navigation; in the next three days, the Oak, her crew and the local harbour pilot surveyed the port and repaired several buoys whilst installing a handful of new ones.

Because of the relatively unknown status of the port and distance to other suitable ports, the initial logistics concept evolved to one centred on a Joint Logistics Over the Shore (JLOTS) model.

Logistics over-the-shore (LOTS) is the process of loading and unloading of ships without the benefit of deep draft-capable, fixed port facilities; or as a means of moving forces closer to tactical assembly areas

Joint Publication 4-01.6

The UN Food Cluster estimated that 140,000 tonnes of food and 160 tonnes of high-energy biscuits would be needed, the latter for places where fuel for cooking was unavailable.

By Saturday the 16th of January, US forces were operating to four basic principles;

- Command and control of supplies flowing into the logistics hub at Guantánamo Bay

- Expanding the USNS Comfort (hospital ship) capacities in readiness for deployment

- Port clearance at Port-au-Prince

- Water and MRE inflows via any routes possible

The USNS Comfort hospital ship left the port of Baltimore on the same day.

On the 17th of January, the USCG Cutter Oak arrived and after dropping off relief supplies at the South pier embarked on her main task of establishing safe navigation; in the next three days the Oak, her crew and the local harbour pilot surveyed the port and repaired several buoys whilst installing a handful of new ones.

Leading the Coast Guard response was the 11-person Maritime Transportation System Recovery Unit (MTSRU), a rapid response unit whose role is to restore cargo traffic to damaged ports or those suffering from some other incident.

Aboard the cutter was also a command and control cell, responsible for coordinating port movements in cooperation with what was left of the Port-au-Prince Port Authority (APN).

Also on the 17th of January, the Dutch support ship HNLMS Pelikaan arrived and dropped off relief supplies at the South Pier.

The US Naval Oceanographic Office sent a Northrop Grumman Compact Hydrographic Airborne Rapid Total Survey (CHARTS) team from Nicaragua for five days to collect data about the port.

CHARTS was a sophisticated system that used a SHOALS topography/bathymetric LiDAR, DuncanTech small format RGB camera and a CASI-1500 hyperspectral sensor on Beechcraft King Air 200 turboprop aircraft.

Post-processing took place less than 24 hours after it was collected which allowed the team to provide soundings, contours, digital elevation models, large-scale charts, and orthorectified image mosaics to Google for inclusion in their mapping products which were also being augmented with GeoEye high-resolution satellite imagery.

The CHARTS team was asked not to return to Port-au-Prince because of airspace congestion.

Aerial surveys and satellite imagery started to build up an accurate picture of the port, joined by the US Coastguard teams in the port, supplemented in the coming days with teams from the US Navy and US Army, layers upon layers.

Whilst this was happening, local shipping, such as the ferry Trois Rivières shuttled people and supplies along its normal coastal routes, with many trying to leave Port-au-Prince

18th of January 2010

Monday the 18th was a key date because it marked the arrival of specialist hydrographic and port survey capabilities and the activation of the US Department of Transport Maritime Administration (MARAD) Ready Reserve Force, an impressive 6 days after the earthquake.

The most up-to-date hydrographic survey of the area was 30 years old.

Underwater debris and changes to the seabed from the earthquake meant a wider area survey was a pressing requirement, especially as larger ships were inbound with much-needed humanitarian supplies.

The US Navy sent the USNS Henson survey ship and a 4-man Fleet Survey Team equipped with survey equipment including a portable side-scan sonar and single-beam echo sounder. They were initially hosted on the USNS Grasp, sister ship of the USNS Grapple, both specialist salvage vessels, but were soon set up on the pier from the 18th

Grasp and Grapple were an ideal mobile base for the dive teams as she had a decompression chamber (used to treat a Haitian diver) and her tools and equipment helped the various teams to complete their work. It should also be noted that USNS Grapple stayed the longest.

Joining them on the same day was the Army 544th Engineer Dive Team, who were on an exercise in Belize when the earthquake struck.

The joint team conducted bottom surveys and investigated the piers and quayside for damage.

The Explosive Ordnance Disposal Group 2, Mobile and Diving Salvage Unit 2 and Underwater Construction Team 1 also joined the construction and repair effort at the port.

This pier survey concluded that whilst it was usable, only a third was accessible due to the poor initial state and earthquake damage. 150 piles required some form of repair between 2 and 8 feet (2.44 m) below the waterline, and 66 piles required repair above the waterline.

The team determined that only one truck at a time could drive on the South Pier before it had been repaired.

This was a problem.

The Fleet Survey Team then moved to the USNS Henson and completed an anchorage survey for the en-route hospital ship USNS Comfort.

When this task was completed, they joined the team at the port to carry on with general survey tasks, including installing tide gauges and using their Expeditionary Survey Vessels for hydrographic surveys.

Using commercial ‘fish finder’ sonar technology and survey-grade GPS receivers they provided soundings and side-scan information around the piers. They also identified a narrow channel through a surrounding reef that enabled the use of a nearby beach as a landing spot for the movement of heavy equipment via causeways.

MARAD announced the activation of the Ready Reserve Force (RRF).

U.S. Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood announced that the Department’s Maritime Administration (MARAD) is sending five ships to assist with relief efforts in Haiti. Gopher State, Petersburg, Huakai, Cornhusker State and Cape May are being prepared to sail to the Caribbean Ocean from different parts of the United States. All are owned or controlled by MARAD, and will be crewed by civilian U.S. merchant mariners.

“Sending these ships will help those on the front line of this effort save as many lives in Haiti as possible,” said Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood. “These ships will add crucial capabilities by supporting operations to move large volumes of people and cargo.”

“Once again the U.S. Merchant Marine is answering the call for assistance, as it has done since our Nation began,” said Acting Maritime Administrator David T. Matsuda. “These ships and skilled crews are ideally suited to assist in Haiti by providing unique capabilities. One cargo ship can carry as much as 400 fully loaded cargo planes.”

M/V Huakai is a new high-speed ferry capable of speeds of nearly 40 knots in the open ocean. Petersburg, Cornhusker State, Cape May and Gopher State are part of MARAD’s Ready Reserve Force (RRF), which includes a total of forty-nine ships at ports around the country.

Marine Link

Another less well-documented survey on the 18th, but pivotal, nonetheless, was completed by a civilian team.

Crowley Maritime, a US marine services company on contract to the U.S. Transportation Command (USTRANSCOM), actually chartered a small float plane to take a survey team from Titan Salvage to Port-au-Prince on the 18th of January.

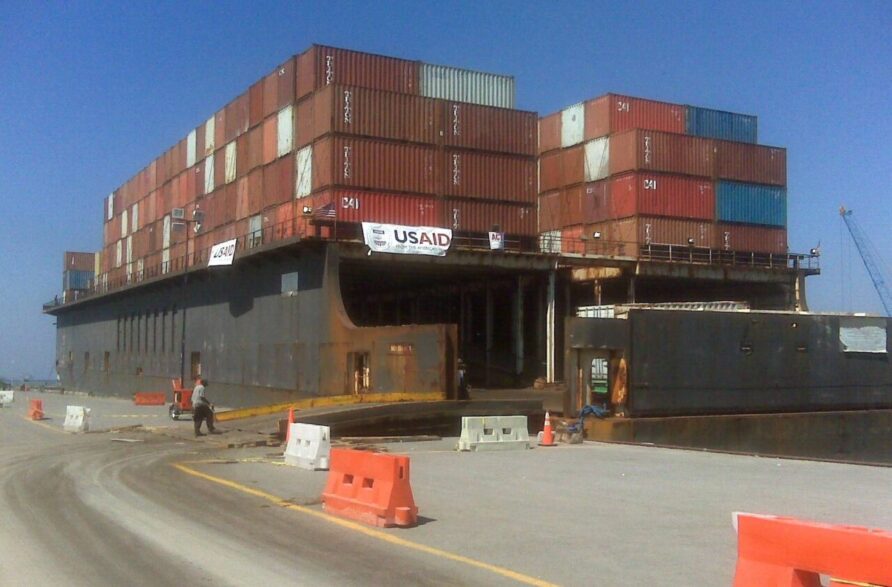

The Titan Salvage team concluded that it would be possible to effect a temporary docking structure in the port using a 400ft (ca. 122 m) x 100ft (ca. 30 metres) barge and a crawler crane. The day after, the barge 410 was on the way from Texas with an expected arrival time of February the 2nd, 2010.

This would be pivotal, but back to the port.

On the 18th, the barge Crimson Clover, with over 123 20ft (6.1 metres) ISO containers, arrived offshore.

The barge was already inbound to Haiti when the earthquake struck but because the state of the port was unknown when it arrived, it was ordered to hold.

The Crimson Clover was subsequently allowed to dock at the South Pier to offload her cargo

One truck at a time.

USAID had by then also contracted with shipping companies to transport 10,700 tonnes of food, approximately 560 containers worth, to Haiti. America Cargo Transport Corp was preparing the barge American Trader and the ocean-going tug Justine Foss to carry approximately 5,500 tonnes of food and other supplies to Haiti.

By the end of the 18th, a full understanding of the state of the port was available, a large barge had proven that with restrictions, the South Pier was viable, the American Trader barge was on its way, and MARAD had activated some unique vessels.

A large amphibious force was also inbound, or already in place, delivering smaller quantities of aid at multiple points.

Problems at the Pier

There were some frustrations in the press about the lack of progress.

Getting the port even partially operational would allow officials to speed deliveries of humanitarian aid and supplies and relieve the airport, also making it easier to resume commercial flights to Port-au-Prince. Two other Haitian terminals, used to bring in fuel, have also been heavily damaged, said Reginal Villard, a Port-au-Prince shipping agent.

Relief organizations and commercial shippers are champing at the bit to get cargo in and unloaded. On Tuesday, the Coast Guard told Mr. Villard he could unload a barge carrying 123 containers of emergency aid towed by a tugboat from Alabama through Puerto Rico to Port-au-Prince. But it would have to be done gingerly, he was told.

Crowley Maritime Corp., a Jacksonville, Fla., shipper which operates throughout the Caribbean, said it will conduct a test beach landing on Friday. A Crowley ship carrying 12 containers loaded with water and ready-to-eat meals will anchor off Port-au-Prince, a spokesman said. A smaller vessel, with a crane aboard, will be waiting to unload the containers and carry the supplies to the beach.

Crowley also plans to bring a barge in by Feb. 2 and “put it on the beach to have it serve as a makeshift dock,” the spokesman said.

Wall Street Journal

AP released two video reports on the 19th that described the problems at the port.

One…

Two…

The French landing ship Francis Garnier arrived and offloaded supplies at the South Pier on the 19th, unloading stores, vehicles, and construction equipment.

The Batral is fully loaded: 2 backhoe loaders, 3 mini-excavators, 2 trucks, 1 4×4 are parked on the bridge. The amphibious building also brings a medical team, an ambulance, 700 tents and humanitarian cargo for the Red Cross.

Not everyone was happy

The Americans weren’t happy that a French naval vessel, the Francis Garnier, had docked. They weren’t being competitive. They were being cautious. The French ship and its cargo could have tipped the pier over like an empty paper cup.

One of the Navy divers said, “Put on your life preservers.” He wasn’t kidding. Nearby, the civilian engineer for the Navy had made a pendulum out of a piece of string, a twig, and a weight — a half-full plastic eyedropper. He told a sailor to keep an eye on it.

“If it starts to swing, run,” he said.

Washington Post

The HNLMS Pelikaan also returned the same day.

Work on clearance continued and having completed unloading, Crimson Clover departed.

The USNS Comfort arrived offshore on the 20th.

The excellent G Captain blog produced a graphic showing all the international vessels engaged with the relief operation, click here to view.

By the 20th, ten days after the earthquake, supplies had started to arrive overland from the Dominican Republic, the operation at the airport was getting into full swing and helicopters from various US ships were ferrying small quantities of water and medical supplies.

Dutch, French, and US Coastguard vessels had offloaded some supplies, and survey and initial port rehabilitation had begun, but the bulk of the food supplies had arrived almost by luck, on the Crimson Clover barge.

Helicopters from the first large US Navy ships, the USS Carl Vinson, for example, arriving on the 15th, had started to move supplies, but volumes were limited, despite the hugely impressive effort. She had offloaded combat aircraft and embarked helicopters, 19 in total, on the way to Haiti.

USS Bataan was activated as the Ready Duty Amphibious Readiness Group, including USS Fort McHenry and USS Carter Hall. USS Gunston Hall also joined the Bataan ARG/MEU, arriving on 18th January.

A total of 48 helicopters were by now in operation.

Seacor had responded quickly to the earthquake and had a couple of S-76A helicopters from its aviation division and a pollution control vessel called the NRC Perseverance arrived at Terminal Varreux to begin repairs.

Scientists from the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York also used LIDAR equipment to support mapping using a Piper twin-engine aircraft, with flights on the 22nd of January.

The Twin Tracks of JLOTS and Port Rehabilitation (to the end of January 2010)

Food, water, shelter materials, medical supplies, engineering plant, cooking equipment and assorted construction supplies were all waiting to come ashore. Although responders were utilising the airport, other smaller ports, overland routes, helicopters and airdrops, the main event was still the seaport(s) in the Port-au-Prince area.

This would proceed in two parallel tracks;

- Getting the marine terminal back into action

- Over-the-beach amphibious capabilities, or JLOTS.

Direct from Florida, the first LCU of Joint Task Force – Port Opening (JTF-PO) Seaport of Debarkation (SPOD) arrived on the 20th of January, and the second the day after, as shown in the satellite image below.

The team established a 24×7 shift system and assumed port management duties with local authorities and other US forces.

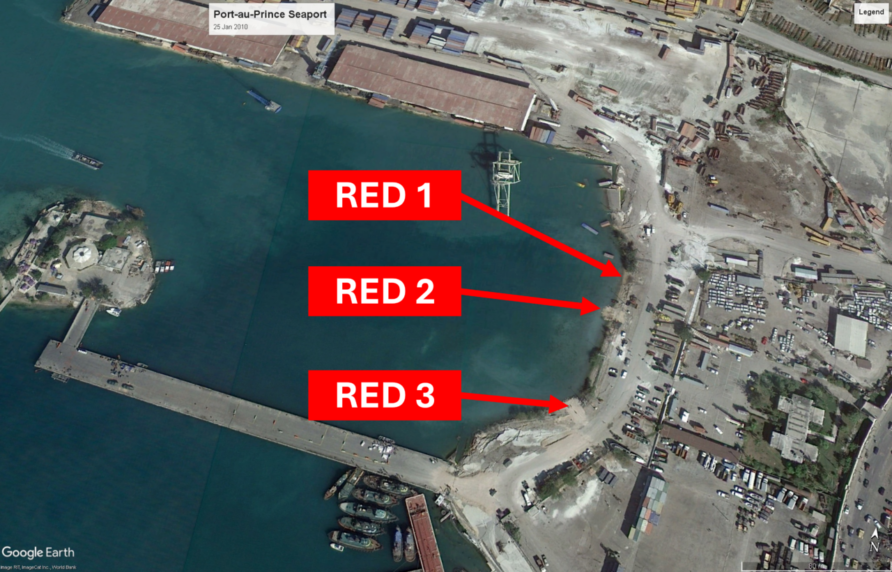

Three landing locations were designated, Red, White, and Gold Beach.

Red Beach was the main terminal (at a couple of locations), White Beach near the Terminal Varreux (established much later) and Gold Beach nestled between the two.

Working with local authorities, the JTF-PO arranged equipment and materials to build three compacted earth and gravel RORO ramps, Red 1, Red 2, and Red 3.

In the seaport, containers were cleared, and underwater obstructions were removed.

- Red 1; able to receive Improved Navy Lighterage System (INLS) and Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) size vessels

- Red 2; able to receive LCU-class vessels

- Red 3; able to receive Logistics Support Vessel (LSV) class vessels

On the 22nd of January, Crowley Marine unloaded fifty-six 20ft (6.1 metres) ISO containers of food and water at Ria Haina in the Dominican Republic from the MV Marcajama for transfer overland to Port-au-Prince.

12 containers were left loaded on the ship, for an experiment.

Sailing to Port-au-Prince, the Marcajama offloaded the containers whilst at anchor to a RORO landing craft operated by G-and-G Shipping called the Cape Express.

Cape Express offloaded the containers using the newly built RORO ramp at the seaport (Red Beach), shown in the image below taken on the 22nd.

The 2.1m draught Cape Express was chartered from G&G Shipping (now Seacor) and built by St Johns Shipbuilding in Florida. She was to carry up to 26 TEU in roll-on-roll-off configuration or if stacked, 46 TEU.

Encouraged by its success, Crowley ordered the Macarjama to sail to Miami and return to Port-au-Prince with a full load of containers.

CNN reported a strong aftershock that required closing the South Pier

A 5.9-magnitude aftershock Wednesday stopped efforts at the pier for about three hours. U.S. Navy divers had to go back in the water and reassess the pier’s structural integrity, officials said. There was no immediate word if two less intense aftershocks Thursday, measured at magnitude 4.9 and 4.8, also caused a delay.

CNN 22 Jan 2010

JLOTS is the US terminology for a Navy and Army combined capability to load and unload ships without port facilities. JLOTS has a wide range of equipment, but the key to operations in Haiti were the Improved Navy Lighterage System (INLS) and a landing craft or lighters.

JLOTS arrived in Haiti between the 22nd and 31st of January on the USNS 1st LT Jack Lummus, USNS PFC Dewayne T Williams, SS Cape May and SS Cornhusker State.

How did it all fit together?

The SS Cape May (and her sisters SS Mohican and SS Mendocino) are a unique class of vessels called Seabee Barge Carriers. Originally for civilian use, their role was the transport of large lighters or barges over long distances, on three decks.

They move the barges onto the stern-mounted submersible lift, which is lowered into the water.

The lift has a capacity of 1,800 tonnes and the ship can carry up to 38 barges (although fewer are assigned). Instead of barges, other pontoons and small vessels can be carried.

For the Haiti response, SS Cape May bought the Improved Navy Lighterage System (INLS) components comprising three Causeway Ferries, three Warping Tugs, one Roll-On-Roll-Off Discharge Facility (RRDF), three NL Causeway Ferries, and 2 Side Loadable Warping Tugs.

INLS pontoons were also used to create causeways that allowed landing craft and other INLS pontoons to unload without beaching, White Beach is shown below.

1 LSV-1, 5 LCU 2000s, 1 LCM 8 and 2 MFP Utility Boats completed the JLOTS equipment.

Once offloaded, the INLS equipment would be used to unload the Lummus and Williams and transfer the containers, stores, and vehicles to shore.

Another important piece of the JLOTS jigsaw was the USNS Cornhusker State, a dedicated crane ship that could stand off about 3 miles (ca. 5 kilometres) from shore and transfer containers from one ship to the lighterage.

Supplementing the JLOTS equipment were USMC LCAC’s, LARC’s and other landing craft.

Whilst the JLOTS capability was being established and used, survey and salvage operations continued in and around the Port-au-Prince marine terminal, the USNS Henson starting a multibeam echo sounder survey on the 23rd for example.

The INLS equipment was used to bring heavy equipment and stores into the port.

On the 24th of January, the French amphibious vessel Sirocco arrived off Port-au-Prince. The image below shows one of her landing craft using a Red Beach RORO ramp (with an LCU 2000 in the background)

On the same day, the Greenpeace ship Esperança, the Pelikaan (again) and the Colombian Navy ARC Cartagena des Indias offloaded supplies, using landing craft as lighters.

Six Army LCU 2000 vessels arrived on the 25th one shown below.

They could access the RORO ramp at the Terminal with a large engineering plant or containers.

Work continued in and around the port.

On the 26th of January, the south pier was closed due to the discovery of additional cracks, not found in the initial survey because of extensive marine growth,

On the same day, Seacor and the WIN Group (owners of the Varreux Terminal) announced they had started a work package to resume operations to support the receipt of petrol, diesel, fuel oil, propane and edible oils. A 200m temporary pipeline would be installed.

Several aftershocks and usage contributed to the damage. A secondary survey confirmed the South Pier was repairable, and the team got to work preparing the damaged piles for repair.

Repairs would need tools and materials to be shipped in

Problems were encountered, such as the only aggregates available being too large, creating multiple hose blockages that meant some repairs would be made with cement only. Tools also wore out much quicker than anticipated, the diving conditions were bad, and sewage and oil spills compounded an already difficult task.

Nevertheless, the team got on with it.

Another video from AP on the 28th of January 2010 provided an update.

And on the same day, the Washington Post reported that the South Pier was in a poor state.

U.S. Coast Guard officers said Wednesday that Haiti’s main port is more badly damaged than they first realized, a finding that has created another significant obstacle to relief and reconstruction efforts. Word of the hazards reached the command Tuesday afternoon, the officers said, prompting Haitian and American authorities to speed a review of the country’s provincial ports in a race to find more ways to pour supplies into the capital “With the latest on the south pier, we have to look a lot quicker,” Coast Guard Cmdr. Wayne Claybourne said in an interview aboard the Oak, a cutter responsible for coordinating Port-au-Prince’s increasingly busy harbor traffic

Washington Post — Jan 28 2010

The Marcajama returned on the 29th of January, not with 12 containers, but 202. Each was offloaded to the RORO lighters and then onto the seaport.

The barge American Trader also arrived on the same day, so did the SS Cape May.

The American Cargo Transport Corporation (ACTC) American Trader with the tug Justine Foss offloaded 366 containers and uploaded 500 empty containers. ACTC subsequently equipped the barge ZB-1 with a 200-ton Manitowoc lattice boom tracked crawler crane, giving it self-contained cargo-handling capability.

The image below shows the ZB-1 with its crane at the south side of the South Pier.

Causeway ferries and landing craft continued to land containers and vehicles at Gold Beach.

On the 30th, sooner than expected and whilst repairs were still underway, the south pier was re-opened for limited traffic, the same day the former Hawaii super ferry MV Huaka arrived, shuttling between the Guantánamo Bay Naval Base and Terminal Varreux.

She carried 160 passengers and 5,000 MRE, quickly.

Also at Terminal Varreux, the Iver Progress moored, offloading bulk petroleum products.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

The Crowley Plan — February 2010

The Crowley Plan originated six days after the earthquake.

Two large barges would be towed to the seaport, each equipped with lattice crawler cranes and acting as piers for large container vessels.

Both barges would be spudded into place, withstanding berthing forces from larger vessels.

They would connect to the shore with a link span to accommodate large trucks and 40ft (ca. 12 metres) containers.

Because of their size, trucks could drive on, execute a 180-degree turn, and drive off.

Container traffic at the seaport was at its highest since the earthquake.

The international response was surging supplies and all manner of aid into Haiti.

South Pier was severely damaged, but still usable, albeit gingerly.

North Pier was out of use and unlikely to play any further part in the next phase.

Red Beach landing craft ramps had proved invaluable, increasingly used for both break bulk cargo, vehicles, and containers.

Some smaller ports were handling bulk fuel and other cargo and, local contractors were building a RORO ramp at Terminal Varreux

The SS Cape May had offloaded three-quarters of the INLS and lighterage, and Gold Beach was taking traffic.

Cooperation between US and local forces at the port was increasingly effective.

Countries with a regional presence had all contributed with shipping supplies to Haiti using the various routes available.

RFA Largs Bay departed the UK.

It was not enough, but the offload and clearance rates were about to move up a notch.

More shallow draught barges were inbound and offloaded directly without double handling and transferring to lighterage.

The image below shows the American Trader at the South Pier on February 3rd 2010, getting ready to leave after backloading approximately 500 empty containers to make space at the seaport.

The tugs Allie B and Victoria Hunt arrived on the 3rd of February.

On South Pier, the combined dive team continued their work to repair and reinforce it, balancing their safety and the need to maintain traffic flow.

White Beach was established East of Terminal Varreux, mostly for military traffic and as an auxiliary pier for small craft.

Both military and civilian large landing craft continued to use Red Beach 3.

The Sea Express II and MV Cristina Express, both used extensively by USAID, or a US Logistics Support Vessel (LSV), in the image below.

A great deal of behind-the-scenes work between the on-site team from JTF-PO and local contractors and port management meant that containers and other cargo were not just landed at the port, they were moved out of it

The rate was limited by the availability of suitable trucks and drivers, but this too was improving.

On the 8th of February 2010, the 30m piles for the Crowley Barge 410 were being driven, and additional shoreside anchor points (designed by Jensen Maritime) were established at Red Beach 3.

Bulk fuel transfers restarted at Terminal Varreux on the 9th of February.

The Barge 410 arrived on the 10th of February and was secured to the dolphins at the South Pier, next to the MV Nicholas (the Hybur Star and Nicholas had departed by then)

In parallel with establishing the Barge 410, Titan Salvage also continued to work on removing the harbour crane.

Titan Salvage made use of two barges to support gantry crane removal and construction and positioning of the Barge 410

The Resolve Marine RMG300 and Associate Marine Salvage MB1215.

On the 11th, the piling was complete.

The SS Cornhusker State remained on station, often working to ensure containers were ‘contents optimised’

On the 13th of February, the Crowley Barge 410 (APN RED) was ready for traffic, with the first ship arriving the same day, the MV Pafilia.

A link span between RED 3 and the barge allowed vehicles access the barge.

APN RED, or Barge 410, a link span and a big crane, was a significant milestone.

By mid-February, some DoD presence at the port was scaling down as local personnel and contractors re-established and augmented their capacities.

Patients to the USNS Comfort were via Terminal Varreux, allowing Port-au-Prince seaport to concentrate on cargo.

The gantry crane was completely removed by the 18th of February 2010, and on the same day, the British arrived!

RFA Largs Bay and elements of 17 Port and Maritime Regiment RLC used their embarked Mexeflote to offload vehicles and stores at the main seaport, Gold Beach and outlying communities.

After completing the initial deliveries she was tasked by the World Food Programme (WFP) to deliver food to areas that had been cut off by the earthquake, the village of Anse-à-Veau, in Nippes province for example.

The four-day operation at the village delivered 275,000 ready meals, 30 tonnes of rice, six tonnes of beans, more than 200 boxes of corn soya blend, 100-plus boxes of vegetable oil, and 13 bags of salt.

Vessels continued to traffic the RORO ramps at RED 1 and 2, with a Navy Lighterage System (NLS) pontoon providing a link span for deeper draught vessels such as the Crowley Shipper shown in the image below at RED 2., with Cape Express still working at RED 1.

Shippers showed a strong bias to the South Pier and Barge 410 because it eliminated the need for double handling so as the end of February approached, and the second Crowley barge would be ready, it was envisaged the demand for JLOTS and lighterage would taper off to zero.

By the 21st of February, port operations were under the control of the Haitian authorities.

White Beach was still there, but drawdown plans were well underway.

With the gantry crane gone and APN RED at full pace, the Gottwald harbour crane was next, and after some initial disagreement with its owner, removal was underway by the 21st of February

Bulk fuel deliveries at Terminal Varreux were in full operation and the locally constructed RORO ramp continued to provide an additional option for smaller vessels

Additional construction materials arrived to support the final South Pier repairs.

On the 27th of February, the barge Atka (Autorite Portuaire Nationale — APN RED) was in place and the link span was installed.

Normalisation

March 2010 saw the transition to some semblance of normalcy at the Port-au-Prince seaport, arguably better than normal if only seen through the lens of container traffic.

The two APN barges were working well, despite an incident at the beginning of the month that saw an offload error introducing a seven-degree list and some minor damage.

Repair of the concrete piles at the South Pier was well underway, with more equipment and materials inbound.

By the middle of the month, USNS Comfort, SS Cape May and SS Cornhusker State had departed.

On the 18th of March 2010, salvage operations were completed, and all vehicles, broken concrete and cranes were removed.

At the end of the Month, South Pier was in a better shape than before the earthquake.

Haiti is still a deeply troubled country, but its main seaport recovered in the years following the earthquake.

The South Pier dolphins are still there, but their pedestrian footways have not been replaced. The South Pier is in use, North Pier is back to its position as the main facility, completely repaired and extended, supplemented with two barges as used in 2010.

Hopefully, plans for the future come to fruition

The rest of the series

- Introduction

- Over the Shore Logistics in and around Port International de Port-au-Prince

- Air Operations and Toussaint L’Ouverture International Airport

- Observations

Read more (Affiliate Link)

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.