The 105 mm L118 Light Gun has been in service with the British Army since 1974 and has been used continually since.

Although it is a capable system, many now doubt the effectiveness of towed 105 mm artillery against modern threats, and thoughts are turning to replacement options.

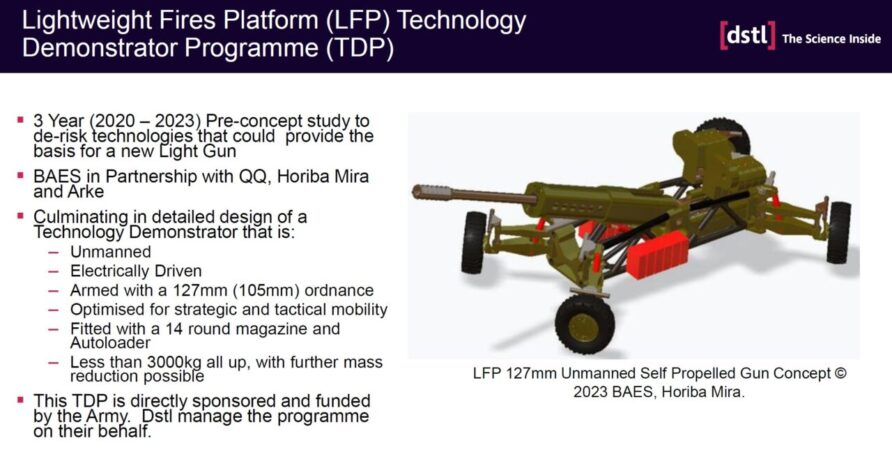

The L118 Light Gun has an Out of Service Date (OSD) of 2030. The Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) and QinetiQ are working on a Technology Demonstration Programme (TDP) to inform replacement options, the Lightweight Fires Platform (LPF).

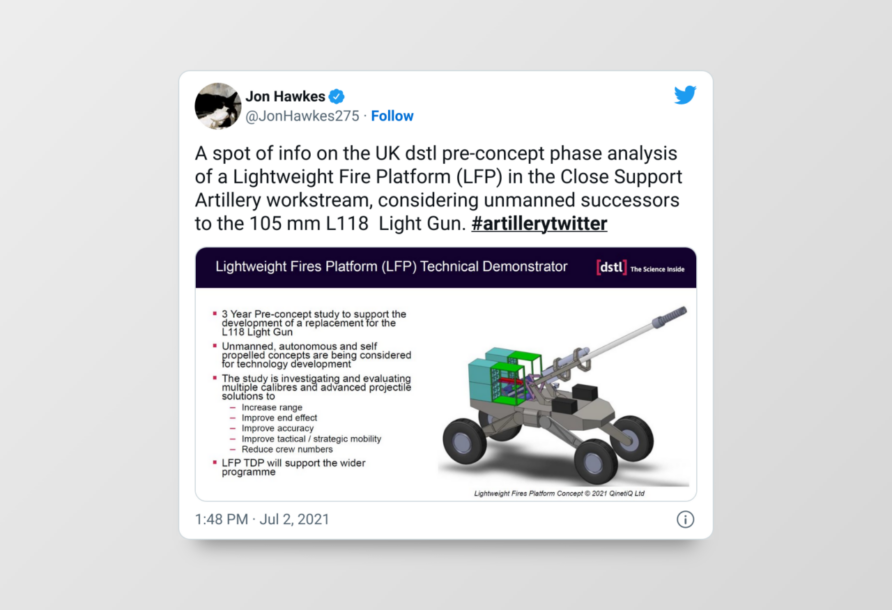

In July 2021, Jon Hawkes from Janes tweeted…

The tweet describes autonomous uncrewed and self-propelled concepts. and with study areas to include;

- Increase range

- Increase end effect

- Improve accuracy

- Improve tactical/strategic mobility

- Reduce crew numbers

Janes reported

Potential options could include a more mobile 105 mm weapon, 120 mm mortar, or a 5 inch (127 mm) naval weapon. An artist’s impression, released by DSTL as an example, showed a mobile 4×4 platform armed with a 105 mm weapon.

A later follow-up revealed some more details.

The 105 mm L118 Light Gun replacement question mirrors that of so many other parts of defence.

A tension exists between ambition and available budget, and the desire to get ahead of the need curve, versus what is good enough today.

Does it contribute to the defence and governmental objectives?

How it will fit into emerging force structures and technology maturity levels.

Are we using the correct process, and do we need a like-for-like replacement?

DSTL will be very thorough, and it will be interesting to see what they conclude. I will in this post look at a handful of relevant issues and pose a few alternatives.

Pallets will feature!

The L118 Light Gun and Future Requirements

In these discussions, we always come back to a discussion on requirements, and what we want.

Why do we need artillery guns in the first place? Especially when there are so many precision missiles, mortars and loitering munitions available.

Targets within the range of artillery can be engaged. If effective targeting and command and control, arrangements are in place.

The long range of artillery produces a large area of influence.

A gun with a range of 10 km can influence an area of over 310 km2 for example. Distribute guns over a wide area or increase range and the area influenced increases.

Many targets can be attacked in that area at the same time or fire concentrated on one.

Effects can include suppression, causing casualties and damage, or destruction. Non-lethal effects include illumination or multi-spectral obscurants (smoke) for example.

Precision guidance kits allow them to attack point targets. sub-munitions dispensers, electronic jamming and even leaflet payloads are available.

For the UK, the L118 Light Gun is in service with light role forces such as 16AAB and 3CDO, although not limited to those.

Mobility is a key success factor and concept of employment.

Some argue that the utility of such forces is low, even against non-peer enemy forces.

The proliferation of low-cost ISTAR and precision systems results in low survivability. My view is that despite this, their utility and value remain. Not every force element can have the protection of a CR3. Not every force element will need to engage heavy armour. Mobility, even at the expense of protection and firepower, has enduring value.

Anecdotal evidence from Ukraine suggests that light-towed artillery is more survivable than many initially thought.

Accepting enduring value means accepting equipment used must be mobile. The mobility of light role forces is compromised by heavy and complex equipment. Reliability is not guaranteed by simplicity, but simplicity has value. Maintainability is also valued, and extensive service support resources are less available.

Historical analysis is only ever one part of looking forward, but it is still important.

L118 Light Gun deployments often illustrate mobility as a key success factor.

Deploying them in ISO containers to the Balkans.

Flying them ashore from an aircraft carrier with helicopters in Sierra Leone.

Stripping and dragging them up a rocky pinnacle by hand in Afghanistan

All are made possible by small size and low weight.

Enabling mobility means understanding the physical constraints of transport infrastructure and equipment. In practice, helicopter underslung weight limits, aircraft hold dimensions and ISO container capacity.

If mobility matters, so do size and weight, a lot.

The Department of Bigger Bangs – Or Why Everyone Likes 155 mm

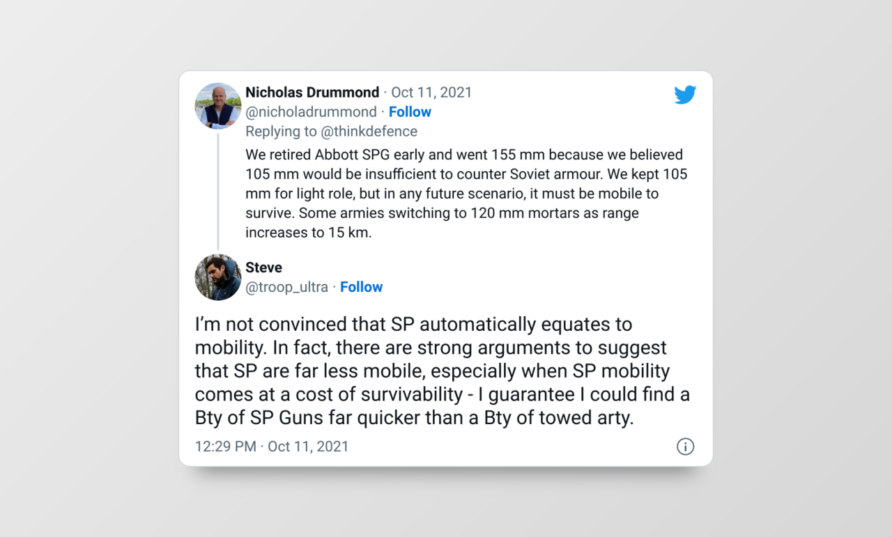

Whilst not directly relevant, it is still worth observing that the 105 mm Abbot Self-Propelled Gun was withdrawn from service because the fragmentation effect of 105 mm was not effective against Soviet armour, which is one of the reasons why the AS90 is 155 mm.

How artillery works…

Shell fragments create casualties and damage equipment.

Fragments weighing less than a gram are lethal because of their high velocity.

Large fragments from a burst within about 10 metres of a lightly armoured vehicle may penetrate.

Beyond 10m from the burst, fragments damage to optics, antennae and other external fittings of armoured fighting vehicles.

Tyres are likely to suffer.

Fragment density influences hit probability and will decrease with distance from the burst.

The number of fragments is a function of shell size and the amount of High-Explosive. Good fragmentation is a result of approximately 25% of the weight of High-Explosive. The UK 105 mm L50 shell weighs 15kg with approximately 3kg of HE fill.

The distance from a burst at which there is a 50% chance of a person in the fragmentation zone being hit by a ground burst fragment is about 30 metres for L50,

This increases a bit for 105 mm airburst and lot for 155 mm airburst.

The shape and area of this zone depend on the height of the burst and the angle of descent.

Multi-function fuzes are now standard, giving choices of proximity height of burst, point detonating, or delay.

Safe distances for own troops will be greater with 155 mm than 105 mm

This is particularly significant when suppressive fire is being delivered to cover assaulting troops.

155 mm provides much greater volume than 105mm for ‘smart features’

A recent article from the Wavell Room by Dermot Rooney explored the Psychology of Artillery Effectiveness and drew some very interesting conclusions

No doubt the Army needs better long-range artillery to compete with likely threats in the deep battle, but it is in close support that the guns are decisive, and only then when they are closely coordinated with armour and infantry. There is a chance that current studies will repeat the Cold War error of garbage in, garbage out, and buy bigger guns and bigger bangs, when the evidence points to the most profound effect coming from smaller bangs in a close combined-arms battle.

For creating damage and casualties, 155 mm is better.

105 mm is better for suppression and supporting troops in close contact.

105 mm ground bursts produce less ground upheaval which might be a factor for troops closing on enemy positions.

For smoke and illumination, 105 mm is more than adequate.

For light role forces, 105 mm could be better suited, all things being equal.

All things aren’t equal, though.

There is a significant challenge with light forces and 155 mm.

Logistics.

The deciding factor in 105 mm v 155 mm for light role forces is the available lift.

Light role forces will always have limited lift capacity, none more so than UK light role forces.

I cannot see how 155 mm works for UK light role forces without significant investment.

105 mm is also in service.

All the various HE, smoke, illumination rounds, fuzes, practice and ceremonial natures.

We can manufacture them in the UK or buy them from several overseas allies.

Discount moving wholly to 155 mm, as bad as that might be for BAE Barrow and advocates of the M777

120 mm Mortars, Other Calibres and What About Those Loitering Munitions eh

The reporting on the DSTL concept study mentioned 127 mm, an intermediate calibre. The 5-inch (127-mm) 62-caliber Mk 45 Mod 4 Naval Gun system offers potential for commonality. Sharing ammunition logistics with the Royal Navy and developing smart munitions. This is attractive, and the fragmentation and target effects will be superior to 105 mm.

Unfortunately, no other land weapons use 127 mm and haven’t since the days of the 60 Pounder and Green Mace.

Unless there is some collaborative programme, do we want another UK-only system? Do we want to carry all the technical risks in developing a land-based 127 mm gun?

Soviet-era 122 mm is also an interesting option, but are we going to introduce another calibre? I suspect not.

I also discount 122 mm and 127 mm

Replacing 105 mm guns with 120 mm mortars also has many advocates. You would be hard-pressed to find many that think it would be a bad idea.

Our allies use 120 mm mortars.

There is a large volume market and a great deal of investment in novel ammunition.

120 mm mortars have a high trajectory, well suited to mountainous, forest and urban terrain, they can use traditional bipod and baseplate as above.

Fragmentation patterns tend to be more circular, which can be either a disadvantage or an advantage depending on circumstances.

They can be towed by light vehicles.

Lightweight vehicle carriage systems have been used for many years.

A more modern interpretation from NTGS in Spain is shown below.

120 mm mortars such as the Elbit SPEAR can be mounted on light tactical vehicles

Turret mounted, such as the Patria NEMO.

Light role to armoured forces can use the same basic 120 mm mortar bomb.

They have utility for maritime forces also, and commonality advantages are obvious.

Imagine the MoD pulling off a joint RN/RM Army programme to deliver a common munition.

Difficult, isn’t it?

120 mm mortars offer the UK a significant capability uplift at low risk.

120 mm mortars have a tangible commonality and market benefit.

It is difficult to argue against them.

Despite the many advantages, 120 mm mortars do have downsides.

Compare the generally accepted maximum range of 10 km for 120 mm mortars to the 17-20 km range for 105 mm guns.

The area of influence for a 105 mm gun is three times larger.

Can we ignore this, especially for light role forces that do not generally have higher echelon support fires?

This is not a theoretical question.

It is critical if opposing forces have 122 mm artillery.

Operation Anaconda in Afghanistan. The 10th Mountain Division (Combined Joint Task Force Mountain) deployed without M119 105 mm guns and used 120 mm mortars instead.

The mortars only managed to fire 16 rounds before they were challenged by 122 mm D30 guns and 107 mm rockets fired by the Taliban.

Not only were they outgunned, but they were also out-ranged as well.

This caused them to over-rely on airpower.

The unexpected level of Al Qaida resistance forced CJTF Mountain to rely on airpower to provide much needed fire support, including close air support. While not prepared for this, the air component accomplished this feat primarily because it had no major operations other than Operation Anaconda to support. The presence of 105mm artillery might have mitigated this transition from a “metered” air tasking order set up for continuous coverage, to the ability to surge operations and place more responsive fires when and where needed to support ground forces’ operations.

Al Qaida fighters often heard approaching aircraft and retreated into the protection of their heavily fortified defensive positions, often in caves dug well into the mountainsides, and emerged unscathed to continue the ground fight upon the aircrafts’ departure. Adding to the problem, non-emergency close air support to troops could take up to forty-five minutes to materialize. Artillery could probably have provided much more responsive and continuous suppressive fires, with almost three times the range of 120mm mortars, enabling infantry units to maneuver more effectively against defending Al Qaida defensive positions.

Another problem caused by relying solely on mortars involved the clearing of “hot” landing zones before air assaults. Artillery officers later decried the absence of 105mm howitzer fires to suppress enemy resistance on landing zones, which CJTF Mountain faced during aerial insertions, as a failure to remember the lessons of Vietnam and the Soviets in Afghanistan. CJTF Mountain relied far too heavily on the ability to surge airpower assets during the Shah-I-Kot battle due to the lack of artillery.

While airpower ultimately overcame initial difficulties, enemy capabilities, terrain, and system constraints still left mortars at a significant disadvantage. Unlike artillery, mortars required much closer placement to targets, along with stable seating of the baseplate to obtain maximum range effects, thus putting them in the effective fire range of Al Qaida mortars and artillery. The 10th Mountain Division’s 105mm howitzers would have possessed the range to engage Al Qaida positions with little concern about mortar or howitzer counter fire. In addition, several US Army officers with experience in Afghanistan argued that deploying a minimally equipped and staffed 105mm artillery battery to support Operation Anaconda would require only slightly more transport capability than a platoon of 120mm mortars.

Read more: Field Artillery and the Combined Arms Team

Can deployed UK forces rely on such an abundance of close air support and attack helicopters?

I don’t think so.

Mortars cannot be used in the direct mode at low elevation, this flexibility should not be dismissed easily either.

Other factors such as flight time, detectability, and air clearance should also be considered.

There are many arguments for getting rid of the Light Gun in favour of a mounted or dismounted 120 mm mortar

Many of those arguments are even excellent.

Having both would allow the best of both worlds and as usual, there is no right and wrong answer.

But here is the thing…

We can’t afford both, the L118 is in service, whereas a 120 mm mortar is not.

The cost and effort to remove one item from service and bring an entirely different item into service is far from trivial

You all know that.

You all know the complexity of enabling a support infrastructure, training, documentation, support contracts and a plethora of other things.

If we can only have one system, we should go with what provides the most flexibility, and that is not a 120 mm mortar.

For reasons of flexibility and cost-based reality, I discount moving wholesale to 120 mm mortars.

Loitering munitions have many attractions

In some cases, might replace the need for artillery

But across the broad span, don’t seem to be a replacement for guns.

The problem with precision weapons is you need precision targeting systems and people with eyes on the target

They are vulnerable to adverse weather and enemy air defences

More complicated to operate and expensive for many target sets. They are not discounted completely but viewed as complementary capabilities to guns.

Towed or Self-propelled

The next big burning question is towed or self-propelled, tracks or wheels.

Cross-country mobility is limited by the loaded ammunition vehicles, not the gun itself.

Built-up areas are well-endowed with suitable gun positions.

In most parts of the world, there is seldom a need to deploy too far from solid surfaces.

‘Into action time’ is a relevant issue.

The faster this is, the faster a battery can respond to calls for fire when travelling.

Self-propelled guns are the fastest, not least because they have ammunition on board.

Traverse also favours self-propelled guns.

Towed guns usually have a top traverse of about 30 degrees left and right.

Targets outside the top traverse arc require the carriage to be manhandled.

This takes time and delays the response to a call for fire.

This is not a problem with turreted self-propelled guns.

Protection against weather and enemy fire is better with self-propelled guns.

The lower floor of tracked self-propelled guns allows easier ammunition loading.

Tracks are also less likely damaged than tyres by counter-battery fire.

Light role forces are generally not going to have a preponderance of tracked vehicles and for this reason, tracked vehicles are discounted, either a tractor or self-propelled option.

(Yes, I know the Royal Artillery use BV206 vehicles as a towing vehicle for Light Guns, but these are the exceptions)

Wheels become the obvious choice, either as a towing vehicle or if self-propelled.

Detectability is an important factor, and the answers might not always be obvious.

There are some very intriguing options when it comes to self-propelled 105 mm guns.

Mandus (USA) and Bharat Forge Kalyani Group (India) are marketing a low-recoil mounted 105 mm gun, the latter with the former.

Both are designed to be mounted on lightweight 4×4 vehicles and use a development of the older XM204 low recoil system.

I even wrote a little about the Mandus Hawkeye in 2012

They have since developed it further, including a 155 mm version.

The 105 mm system uses a variant of the US version of the L118, the M119.

This is not quite as long-range as ours unless rocket-assisted ammunition is used, but it does provide a glimpse of what might be possible.

Several countries have also just mounted conventional 105 mm guns on truck cargo beds, an example from Hanwha (Republic of Korea) below.

This is a method of improving mobility for their giant fleet of towed 105 mm guns in conventional roles.

Another alternative, from Yugoimport, is shown below

The Mandus Hawkeye is a very intriguing system, certainly worthy of consideration.

There would be only a limited advantage if the specific gun system was used (not the recoil mechanism).

Perhaps a combination of our existing L118 guns and the soft recoil mechanism might offer an ideal compromise.

The video below provides a side-by-side comparison.

Keen-eyed viewers might spot the obvious, those stealthy 105 mm rounds.

Less obvious is that the comparison starts with the M119 barrel in the rear-facing position. This is usually used for the longer road moves, not fast moves between firing locations.

It also means the gun can only be vehicle-mounted.

This compromises flexibility and availability. e.g., inability to be broken down, and only able to be moved by a Chinook as an underslung load, not Merlin.

The Hawkeye has reportedly been deployed to Ukraine, so no doubt will be subject to realistic use.

Because mobility and transportability are, in my view, the key constraints for a Light Gun replacement, going self-propelled is discounted, despite the obvious advantages of something like the Mandus Hawkeye.

A Path Forward for the Light Gun Replacement Project

I have argued above that we stay with 105 mm, and a towed 105 mm of conventional design.

I expect most reading this will disagree.

There are other arguments.

- The British Army has a significant collection of capability gaps and obsolete equipment

- The British Army does not have a bottomless pit of cash

- Light role high mobility forces should attract investment commensurate with their size

- There is only so much technical and commercial risk we can absorb, and let’s be brutally honest, we don’t need another Ajax

This leads me to conclude that the way forward for the Lightweight Fires Platform is a stop.

Then recast as a low-risk, affordable, and achievable, series of improvement projects.

The Light Gun is Dead, Long Live the Light Gun

There should be nothing that requires significant research and development.

Each spiral or project can stand alone.

They can succeed or fail without impacting others.

Low risk, much easier to deliver.

Using much of the existing training and support infrastructure.

These are just a few ideas.

Refurbish and Upgrade

An assessment of the material state of the guns would determine refurbishment potential.

If they are beyond reasonable cost, an external procurement could replace them.

Nexter still makes the LG1 105 mm gun, and the newer Boran from Turkey looks good.

With some investment, the Denel G7 looks very capable.

With about 180 guns in service, a programme of component refresh could be completed.

Not only would it support the UK industry, but we could collaborate with the USA to exploit opportunities arising from their M119A3 programme.

We could build up spares and implement a longer-term industry partnership.

A better power pack or more crack-resistant lower platform is hardly the stuff of sexy PowerPoint presentations but is the path to incremental improvements in reliability and effectiveness.

It is also worth noting that Ukraine has (as of August 2023) agreed with BAE to establish a facility to build new and refurbish 105 mm Light Guns.

The MoD let a £15m contract in early 2024 to upgrade the Automatic Pointing System.

- The INU internal GPS, gyro, and operating boards need an upgrade. As integral parts of the broader INU system, only Leonardo holds the technical knowledge for the internal repair and enhancement of the system. “The INU internal GPS, gyro and operating boards must be upgraded.“

- The LDCU requires both hardware and software updates, including compatibility for Windows 10. This is essential for security accreditation and to fix major functional issues. “The upgraded LDCU must be compatible with the Laser Inertial Navigation Artillery Pointing System (LINAPS), a bespoke diagnostic software.“

- The MVR, a distinct piece of equipment, is essential to the APS’s functionality. The integration between the MVR and LINAPS is critical for maintaining the operational capability of the Light Gun. “If MVR is not integrated with the wider APS, Light Gun will have significant loss of operational capability.“

Improving Vehicles

The Pinzgauer Truck Utility Medium (Heavy Duty) tows the 105 mm Light Gun. It is approximately 5 tonnes, fully laden.

Highly mobile but approaching the end of service life.

This is the critical bit though, they can be lifted by both Merlin and Chinook, and this matters.

The Royal Artillery has also recently started to use Supacat Jackals alongside Pinzgauer.

Whilst there are advantages, having two vehicle types in the same battery is not best for support.

An assessment of the material state and potential for refurbishment would inform options.

Some years ago, Ricardo completed a concept study for Pinzgauer refurbishment, upgrade, and obsolescence mitigation.

New vehicles can be purchased if refurbishment is impractical, there are choices.

Moving beats hiding.

We should aim for movement in high-threat situations numbered in minutes.

Hitching the gun to a vehicle and driving away is easy

The vehicle should carry the 6-person detachment, 15-20 ready rounds of ammunition, and a selection of charges.

One vehicle with detachment and ready-to-go ammunition means a reduction of vehicle count by half.

Neither the Jackal nor Pinzgauer provides this, it tends to be either the detachment or ready rounds, as can be seen by the images above.

Go up in size to the HMT600 chassis and it certainly looks more possible.

Protection from the environment and ballistic protection would be preferred.

Speed and flexibility would improve, and so would survivability.

Wider British Army requirements complicate vehicle choice.

It is not as simple as pointing at a brochure and saying ‘Want that one’

Examples are shown below.

Supacat LRV400.

There has also been a three-axle variant of LRV.

It is not clear from the images whether LRV 6×6 would accommodate both ammunition and detachment.

Military conversions of 4×4 and 6×6 pickup trucks are available.

Ricardo and Polaris have recently demonstrated a militarised Ford Ranger, although it seems doubtful, it could fit 6 persons in the cab, especially if fully equipped.

Other examples

Cab capacity is unlikely to favour converted pickup trucks.

This concept image from Prospeed in the UK shows a Light Gun vehicle based on a 6×6 with the crew on load bed seating.

Slightly larger off-road commercial vehicles and light trucks are more likely to meet towing capacity and cab size requirements.

Examples are shown below.

The KMW Mungo is based on the Hako Multicar 30 municipal maintenance vehicle. The ESK variant has a maximum weight of 5.9 tonnes and can carry 10 personnel and their equipment a total distance of 500 km with a top speed of 90kph. Designed for carrying cargo, the Multi-Purpose Vehicle has a payload of 1.5 tonnes and uses a skip loader rather than a hook lift to reduce height. It would need a crew cab fitting, and this removes any ability to offload a pallet of ammunition, but ammunition carriers could be easily fitted to the space remaining.

The Iveco Daily 4×4 has a considerable user base and has been widely adopted for the defence and utility sectors.

The Iveco MUV (Daily) has been further modified by DM Vehicles in the Netherlands for the Korps Mariniers.

Auchleitner (Austria) sells a couple of similar vehicles, the Mantra, and Carrier, shown below.

4 additional seats and 15–20 rounds of ammunition seem eminently feasible with these examples, and they would still retain the transportability of the Pinzgauer, although not perhaps the off-road performance.

There are other manufacturers of similar vehicles in Europe.

One such example is Lindner Unitrac 1 12 L Drive, which is 5.07m long, 2.08m wide and 2.47m high.

With an empty weight of 3,475 kg, it has a maximum payload of just over 6,000 kg.

It can tow a maximum weight of 10,000 kg.

For snow and very soft terrain, they can also be fitted with tracked wheel replacement units.

It should not be difficult to source a medium mobility vehicle that can be lifted by either a Merlin or Chinook. that can tow the gun and can carry a crew of 6 plus some ready rounds and associated stores.

Urovesa in Spain have also recently introduced the SK95 vehicle, shown below, for towing the 105 mm Light Guns of the 7th Brigade

One final interesting option is a conversion or development of the Supacat Lightweight Recovery Vehicle, based on the HMT 600 chassis.

With a protected cab, the HMT600 would seem to offer a good blend of carrying capacity and protection.

One could certainly imagine the recovery equipment removed and a small crew detachment cab fitted, with the remainder having a tail lift for an ammunition pallet.

Supacat has proposed some variants based on the HMT chassis.

Maybe the answer is staring us in the face.

The good thing about either the LRV or 6×6 Hilux or HMT600 is they all fit inside an ISO container.

The only difference is in weight.

The LRV and Hilux come in at under 4 tonnes, so AW149 and Merlin, are accessible as an underslung load.

HMT600, which has much better protection, weighs about 6 tonnes, so only a Chinook underslung load, too heavy for Merlin/AW149 (the latter of which I am assuming will replace Puma).

This may not matter, depending on what is happening with Future Commando.

A simple choice; protected and Chinook only, or unprotected and Chinook, Merlin and AW149.

All the above options assume the vehicle tows the gun.

A portee-style arrangement might be worth investigating to improve time into and out of action, but this will either increase the size and weight of the vehicle or force the crew onto a separate vehicle.

With a small hook lift from Hiab, Palifinger and Stellar, It is not difficult to envisage some sort of lifting cradle for the gun.

Ammunition Improvements

The Light Gun uses three types of fuse, two HE shells, and three charge systems, plus smoke rounds that are infrequently used.

Consolidate and improve these with a general investment programme.

Logistics and training become simpler, and effects, you know, more effective.

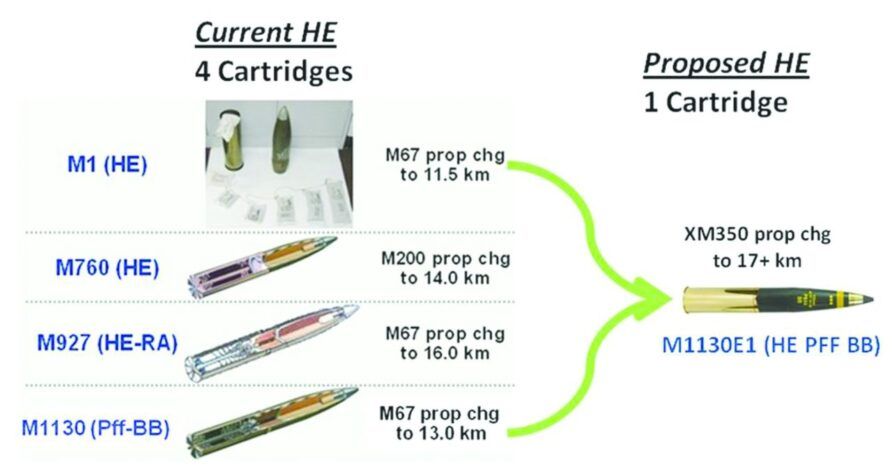

I am not saying the information below is directly relevant to the UK, not least because the US and UK versions of the Light Gun use different firing mechanisms and ammunition, but it is an illustration of how consolidation and simplification can work.

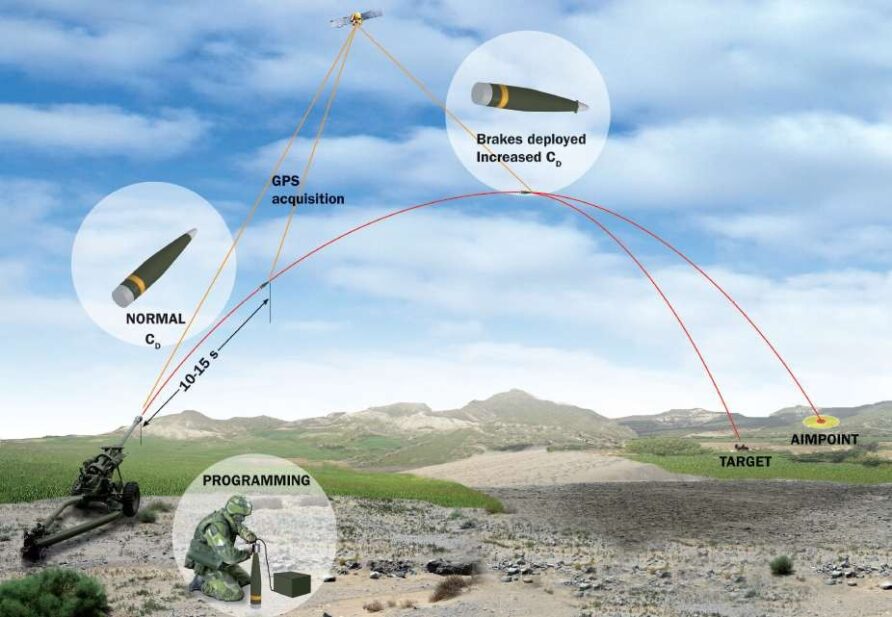

Although not what we might consider as a precision guidance kit, course-correcting fuses can significantly improve accuracy.

They are available off the shelf from several providers and provide a low-risk method of enhancing capability.

Manufacturers’ marketing materials tend to point out that more accuracy decreases ammunition expenditure and improves counter-battery resistance by enabling the gun battery to fire and move out of a position quickly by needing less ammunition for a specific effect.

I am not sure of that, and it would need testing against real-world examples but certainly, a factor to consider.

A few years ago, Junghans Microtec worked on a couple of European course-correcting fuse projects. Reads more here

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Better Pallets

Ammunition for any artillery is always a significant challenge.

For the Light Guns, ammunition is generally moved to the Regimental echelon by a dedicated RLC squadron using MAN EPLS hook lift-type vehicles.

A JCB Telehandler is then used to move those pallets to a central position, from where it is distributed by hand to individual guns.

Air Despatch or support helicopters are also used in some circumstances.

If time is available, ammunition pallets can also be ground dumped at individual gun positions.

Other examples are below.

Can we improve on this with better packaging and handling?

In truth, I don’t know, but one can certainly see a lot of double handling, removing things from boxes that are inside other boxes.

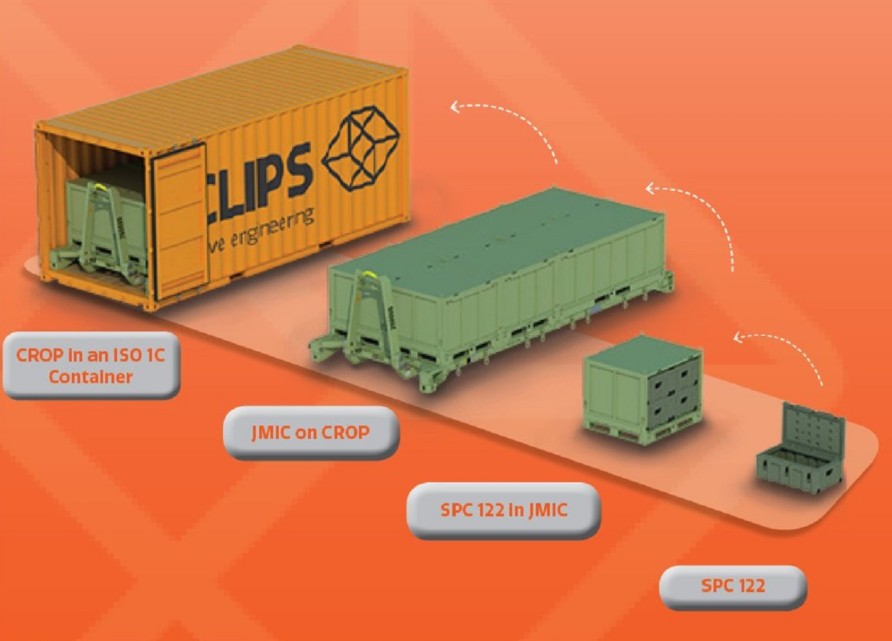

Improving ammunition may resolve some of these challenges, but another system worth a look at is the Eclipse Engineering JMIC.

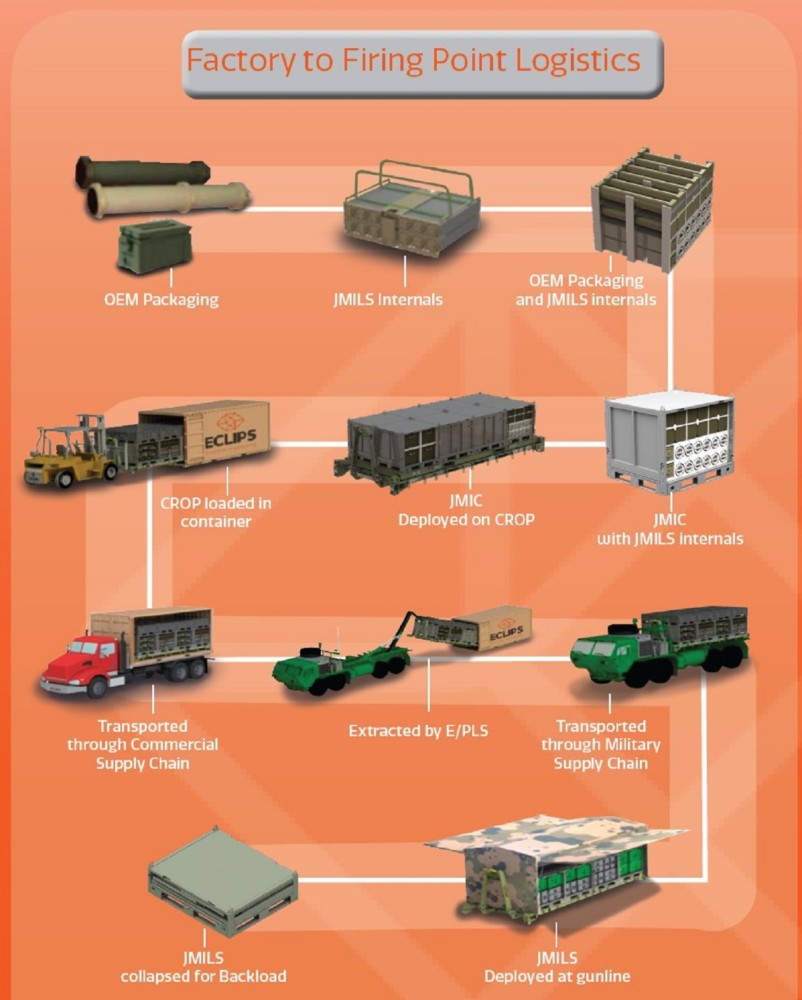

Recognising the poor optimisation of current containers, platforms, and boxes, the US Defense Standardization Department formed a working group to look at several options for improvement

They developed the MIL-STD 3028 JMIC.

The Joint Modular Intermodal Container (JMIC) is a modular stacking container that locks top and bottom to form a single unit.

The basic JMIC box is designed to stack 3 high, be lockable, foldable and has integral tracking.

A series of spacers and forms are used to secure items inside, where the objective is to maximise packing density and minimise dunnage and filler materials.

Multiple JMIC can be clipped together to form a container for larger items, in multiples, up to two times in width and up to four times in length.

They can be stacked three high without additional securing and can be lifted with forklifts or any crane, hydraulic jib or lifting device by attaching chains or strops to the protruding lift eyes on top of the container.

Two can be sling-loaded when clipped together, and four JMIC are designed to fit onto a 463L pallet.

For each large item like ammunition boxes or artillery shells, a stowage plan was devised and appropriate spacer materials were defined.

Joint Modular Intermodal Platform (JMIP); is an intermodal platform (or rack) with integral locking fittings that allow JMIC to be secured without any form of strapping or securing.

JMIP can also be transported on aircraft without a 463L and stacked inside a conventional intermodal container.

This creates a possible replacement for the 463L and the platform to be used end to end, across both land, sea and air supply chains.

I wrote about this in 2014, click here

ECLIPS has developed the JMIC further and developed the Joint Modular Intermodal Logistics System (JMILS).

JMILS streamlines the ‘factory to firing point’ logistics chains.

A single JMIC with JMILS internals could be configured to take a mixed load of shells and charges, sufficient for carriage on the towing and crew vehicle.

This would provide an immediately available supply of ammunition suitable for quick action.

Multiple JMIC could still be used for more homogenous loads of shells and charges and treated as existing pallets, moved through the military supply chain to the gun battery.

A battery would still need a telehandler to move the JMIC from a central point to individual guns, unless some form of small hook lift or pallet trailer was used.

Pallet trailer manufacturers include EHS, Lift n Go and Perimeter Security, the latter produce adjustable trailers that can be used for small containers and concertina wire coils.

The Dutch company Pallet Trailer produces several models for road use, the largest able to lift and carry a 1.8-tonne pallet.

A NATO standard ammunition pallet can carry 36×105 mm shells at approximately 1.3 tonnes.

The principle of operation is the same for all of these, reverse onto a pallet load, align the forks, lift, lock, and drive away.

The lift mechanism can be manual or electrical.

Small hook lifts may also be used.

Demountable systems have conventionally only been used on larger vehicles, but the technology has moved on and the benefits of DROPS/EPLS-like systems are now available on smaller vehicles.

Manufacturers make a range of suitable devices, the lightest only lifts 2 tonnes.

These might enable a different method of ammunition distribution to be used

The Auchleitner Carry comes in a double cab version with a hook lift.

Tail lifts also provide some potential to offload a pallet or JMIC to the ground adjacent to the gun, without requiring extensive manual handling or a telehandler, although these tend to limit vehicle mobility off-road.

Light Gun Replacement Summary and Final Thoughts

Hopefully, I have demonstrated that there are no immediate or obvious answers.

Each approach has strengths and weaknesses that go beyond simplistic comparisons.

Does 105 mm Make Sense?

My view is yes, for the reasons described above.

Does Towed 105 mm Make Sense?

My view is also yes, but within the ‘niche’ of light role forces where mobility is a high priority and area of concern, arguably smaller than for heavier and more mobile forces

Self-propelled 105 mm versus self-propelled 120 mm mortars for mechanised forces is a related but separate issue.

What Next?

The problem I see in many of these discussions is that the gun and its replacement as a singular ‘thing’ when in reality it is an ecosystem of joined up and overlapping components including people, equipment, suppliers, processes, training, logistics and, lots more.

The scope for improvements at a modest cost across this ecosystem is where we should focus, everything from improving and simplifying ammunition to making sure the limber vehicle falls within the scope of programmes like GSUP, better pallets and component replacement.

As boring as this sounds, this should be the focus.

Ideally, and alongside, the UK should invest in 120 mm mortars across a range of light-role and mechanised forces.

Hedging that the range and flexibility advantages of 105 mm can be matched with developments in both loitering munitions and conventional mortar ammunition.

If we had lots of money, doing this alongside significant investment in 155 mm and long-range rockets would be the better solution.

But the lack of is why the proposal described above is to take a conservative approach.

It proposes relatively low-cost incremental improvements at low risk in what is, frankly, a niche capability.

That is not to say it is an unimportant niche capability with no utility in the future, but the main artillery event is elsewhere.

And elsewhere should attract the bulk of our investment.

See you in the comments.

Change Record

| Date | Change |

| 11/02/2022 | Initial issue |

| 02/08/2022 | Update with information on the DSTL programme |

| 10/09/2023 | Update with information on the DSTL programme |

| 04/05/2024 | Update with APS contract |

Read more (Affiliate Link)

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great article as ever! However, exceptional emphasis on the logistics behind the firepower!!

I agree that for now, given budgets and requirements, an enhancement package for the existing Light Gun seems to be the most sensible way forward for what is essentially a niche capability.

I do think that eventually the 105mm LG gets replaced by a 120mm mortar for all the reasons you mention in the article, from range of weapons systems – base plate & tripod manually loaded, powered deployment from a light trailer, vehicle mounted with aiming by an FCS, all the way to a NEMO on Boxer…. all able to fire a very broad range of ammunition.

You do note that right now a 120mm mortar cannot meet the range of the 105mm Light Gun – I would say that will change very soon. Elbit have a 120mm mortar round that can already reach 16Km – just a smidge short of the LG’s 17Km!

This PDF from 2016 shows that the US has already tested a wing-equipped guided 81mm mortar round out to 19Km: https://ndiastorage.blob.core.usgovcloudapi.net/ndia/2016/armament/18279_Steelman.pdf

The same deck mentions the same tech added to 120mm rounds to get out to 30Km – not sure where this went, what happened to funding as I am pretty sure its not in production for the US Army – BUT- the point is, the tech was in testing 8 years ago, it is not, as they say “rocket science” :-)

The limitation of the artillery system has always been the ammunition train. The mounted double 120mm mortar system is very attractive, provided it is used in sufficient numbers in support of dismounted infantry – say a mounted 120 mm mortar company per battalion. The range/area of influence factor in favour of 105 mm is compelling, provided the whole transport system can be kept mobile. The risk for UK is that 105 mm Light Gun will not be replaced at all. I agree that our main effort of artillery rearmament should be SP 155 mm. But it is essential that we see the gun, ammunition, transport and manning as a whole system. We need long range and numbers of guns to achieve real effect, even with MRSI!

An important question to ask is what the formations equipped with this gun or is successor shall be capable of in the future.

The answer might differ from the status quo.

Both towed transportation and helicopter mobility can be utterly useless in certain scenarios. A 105 mm gun or 120 mm mortar is going to be outranged by 1st and 2nd rate opposing forces’ artillery. Its survivability cannot rest on range, so it has to rest on either stealth or mobility or both.

There’s also the question of endurance in battle. Is the solution capable of delivering 450 HE shots in a most intense battle day? Combat in Ukraine peaked at such intensity few years ago.

as per Jed,155 PLUS a niche capability… that we are talking about there.

The Husky that ,under the OUVS programme, the UK Ministry of Defence got in at great numbers to replace its RB44, Pinzgauer and Land Rover capabilities??

While we are in such a hurry to junk them, there is the flatbed and the command post while Coyote (less protected) could well be the gun limber

… Should Husky be in the article, if not as a proposal but at least a benchmark in the Pinzgauer replacement discussion? Or would that be crying after spilt milk😎

And, as an aside, of course AMOS for the AI Infantry

; with three units per bn, how many would we need to buy🤣

I think with the increase in range of opposing artillery and battlefield surveillance a towed 105mm is dead. A self propelled 105mm with an autoloader mounted on something like a robotic ATV is a viable replacement and could allow increasing battery strength with the same manpower. Any larger gun would require a full size vehicle and negate its compact size and portability.

However a battery should also be supplemented with a precision fires component; a light vehicle carrying a dozen or more suicide drones or missiles to allow them to engage hard targets/targets of opportunity slightly outside their ballistic range or provide precision strike and should have a basic recon UAV at their disposal as well.

I would like to suggest that the most important role that the current light gun fore fills is that of providing suppression on an opponent. Continued suppressive effect is what enables manoeuvre forces, in this case light infantry to close with a opponent and get into close combat. Without this suppressive effect the infantry by doctrine cannot do their job.

Due to its recoil systems modern artillery has the ability to continue to fire on to a position without pause for days on end – if we take WW1 and WW2 as an example. Mortars, such as 81mm and 120 mm are not designed to provide this long term suppressive effect. They are designed to provide short term weight of fire power combined with tactical mobility. Due to the fact that the firing forces are transmitted from the base plate into the ground without any sort of recoil system they have a limited capacity to maintain continued suppressive fires. Anyone who has used a mortar in softer terrain while have seen how quickly they can bed themselves into the ground and literally dig them selves into a huge hole in the ground requiring the crew to be frantically digging until it becomes unsafe – I know that some of the heavier mortar systems mounted on Armoured fighting vehicles can maintain this suppressive fires but now we are no longer talking about a system that can support light air or sea mobile infantry.

If we take the average time an infantry quick attack at the company level a rough timing estimate should be about 45 minutes to prep, give orders, and move to the start line, then about 15 minutes per platoon objective. SO any Light gun replacement has to provide suppressive fires for at least 90 minutes.

I further argue that precision drones are not at the stage just yet where they can do this function.

The So what is unless there is a revolution in drone technology ( possible) or in mortar technology ( possible) the only sound replacement for the light gun is some sort of artillery system.

In fact I would argue that the L118/l119 light gun does not really need replacing, rather a better bet is to invest in developing new ammunition with greater range, that is more lethal and more accurate.

Great Article, but one perspective that I did not see, was the impact of electrification of vehicles and how could this improve their capability in the towed howitzers paradigm. What i mean is, either we could use almost like a plug in APU (Auxiliary Power Unit) + Trailer for the ammo like the Plasan ATemm (190 HP Power + 1.2 Tons Payload) …. other approach, would be to replace the wheels of the gun (that have no traction / are unpowered) by "Direct-drive in-wheel electric motors" (like the ones of the company Elaphe) and upgrade the electric power pack / generator so that besides powering the FCS and Gun Laying Electronics would also power a battery pack / or when being towed would regenerate the battery pack…. somewhat a lightweight / low complexity conversion into a self propelled gun (for short range change of position after fire without the dependence of the towing vehicle).

There will always be a place for a 105 gun. The Army must be prepared to fight both against peer-state nations but also smaller operations and counterinsurrgencies, which require agility and speed. The 105 allows manouverability and ease of insertion with a small footprint, still allowing direct fire if necessary, which a mortar cannot provide. A 105 must remain as a side-arm in the armoury. But for goodness sake get rid of those ridiculous pinzgauers, the only place they are fit for is salisbury plain.

Just wondering if some consideration could be given to the G7 LEO. A 105mm which claims 30km+ & to solve some of the lethality issues of the 105mm was also offered in an SPG version on a piranha chassis for US Stryker Brigades https://www.globalsecurity.org/military//world/rsa/g7.htm

Considering RBSL includes Rheinmettall that now owns Denel I'd have thought it could be a first port of call for DSTL.

But not sure if other than money there were other issues.

Keep up the great work

Soft recoil 105 is apparently in Ukraine on the back of a Hummer.

https://www.twz.com/land/humvee-mounted-low-recoil-105mm-howitzer-to-make-combat-debut-in-ukraine

As a user of the 105mm Light Gun for over 26 years, I have always felt that its differentiator was the portability, to get where other systems cannot and provide the firepower to start the Battle Winning process.

Now more than ever, I feel a move to the 120mm Mortar, with a range of flexibility to mount and dismount from an agile platform will allow the gap with enemy to be closed whilst maintaining the ability to remain mobile and avoid the detection (inevitable with modern Target Locating systems) turning into destruction of the asset.

I believe we need to think of adopting an offensive posture with the mobile assets, as well as occupying the fringes of the battlefield to provide a more asymmetric ability to provide fires to the Infantry whilst affording as much autonomy and protection as possible from the ability to 'Shoot and scoot'. Short, Medium and Long Range Artillery should be centred on Survivability, so the ability to move immediately after unmasking a position is well served by the mobility of a vehicle mount capable 120mm Mortar >15km, Archer >30km and HIMARS.30km+ type platforms.

Light and fast modular logistics is needed to support all of these, so we need to move away from excessive packaging which is outdated, and move to more manageable systems as described in the article, which is great.