A proposal to re-establish Army Air Corps fixed-wing light transport aviation to support the British Army Rangers.

The Rangers need Air Mobility

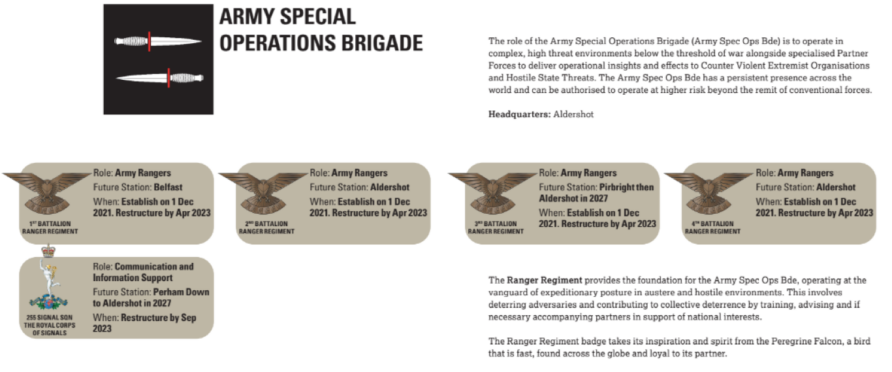

The Army Special Operations Brigade and Rangers

Defence in a Competitive Age, published in 2021, described the British Army Ranger Regiment as;

A new four-battalion Ranger Regiment will be formed in August 2021, seeded from the Royal Scots Borderers, 1st Battalion Royal Regiment of Scotland; 2nd Battalion, Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment; 2nd Battalion, Duke of Lancaster’s Regiment; and 4th Battalion, The Rifles. The new regiment will sit within the redesignated Specialised Infantry Group, becoming the Army Special Operations Brigade.

Future Soldier described their role and organisation further, within the context of 6 DIV

There were many questions about the Special Operations Brigade then, and there are just as many now.

An article in the Wavell Room describes the gamble;

The Army Special Operations Brigade is an additional gamble, but it is a gamble that the Army has had to take. In its quest to demonstrate utility, the Army has had no choice but to develop a concept, not necessarily based on any sound academic, historical, or demonstrable examples of success.

UK Land Power also describes limitations;

Thinly deployed around the world, they will be entirely reliant on local forces to step-up when the use of force becomes necessary. As good as Ranger Regiment battalions may be in time, there is a hard limit to what they will be able to achieve.

As many noted, the British Army has been covering partner capability development for decades, and more recently going through several different ways to describe the same thing.

Specialised Infantry, Mentoring, Regionally Aligned Adaptable Force Brigades and the Security Force Assistance Brigade might all be recognised terminology from today or yesterday, but fundamentally, are all components of the wider definition of Defence Engagement.

Upstream conflict prevention, is a simple concept that at its core seeks to make the UK safer by providing help to unstable nations such that they can help themselves to stabilise. The theory is that an Ounce of prevention saves a Pound of cure. Getting in early, de-escalating early-stage conflict and supporting overseas development efforts are all seen, quite rightly, as effective means of preventing wider and much more expensive conflict.

The armed forces conduct upstream conflict prevention missions all the time and can range from training on an opportunity basis to more involved and lengthy engagements. Some no doubt are successes, others less so, that, of course, being the nature of the beast.

With this long and perhaps not always enduring focus on defence engagement. it is probably fair to suggest that the Rangers and Special Operations Brigade are both works in progress, not helped by distractions like articles on new rifles and better combat pants.

For it to mature, the British Army needs to answer a few questions on;

- The political will to move from assisting to accompany

- The difference between SFAB and SOB, and how the SOB fits into the wider conflict prevention and defence engagement landscape

- How it will resource a move beyond light infantry activity

The third question has always been at the centre of my thoughts on the Rangers and SOB, how do we move from dismounted infantry activities into those that provide more value add, especially those that can leverage the small force and the British Army’s technology and technical advantages?

Communications, ISTAR, UAS, complex weapons, mobility, logistics, medical, and combat engineering are all technologically demanding endeavours that many partner nations will struggle with and whose application can make a disproportionate impact.

A question on Ranger’s mobility neatly brings me to aviation.

The Air Component

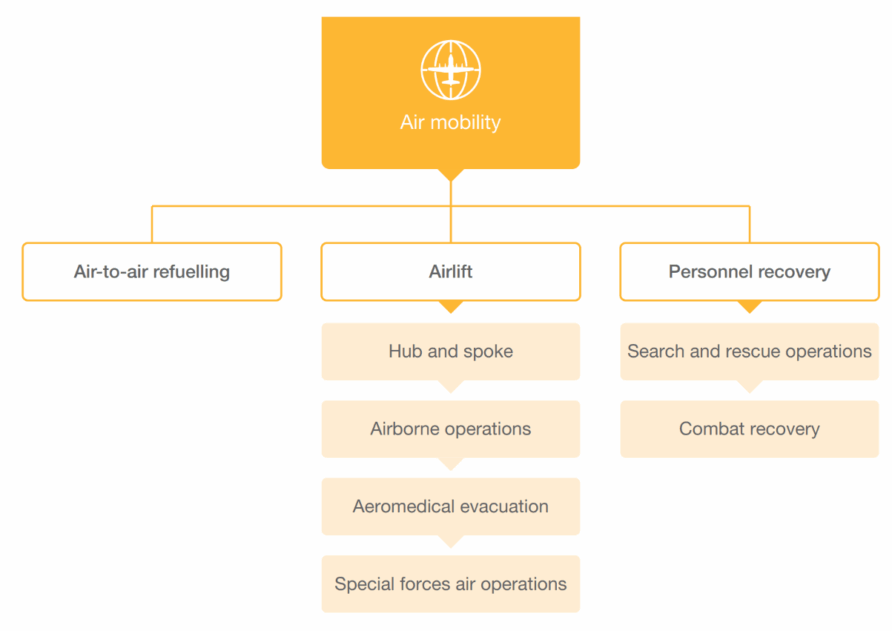

UK Air Power defines UK Air and Space Doctrine, particularly the three core air power attributes;

Height, speed, and reach, and following from that Air Mobility

And describes air mobility as…

Air mobility provides the ability to deploy, sustain and recover personnel and equipment, often over significant distance. The speed and reach of air power offers the ability to create rapid strategic influence in support of UK national objectives or in support of allies, such as through the insertion of special forces or delivering humanitarian aid due to a natural disaster. At the operational and tactical levels, air mobility supports land operations by enabling manoeuvre when movement on land is particularly difficult due to poor terrain, poor roads or unacceptable threats to land forces.

The document also describes the role of air power in defence engagement and conflict prevention, the same set of core principles that underpin the Special Operations Brigade and Security Force Assistance Brigade

Whilst the British Army can train an infantry soldier from Sierra Leone in first aid or section attacks without needing Challenger 2 tanks, it is more difficult (although not impossible) to exploit the many advantages of air power without aircraft.

Although the RAF conducts defence engagement activity with many nations and like the other services, has many nations wanting to come to the UK for training, the complexity of the RAF’s basic equipment does have a limiting effect on the types of defence engagement activity it can carry out.

For many years, the gulf between modern Western combat aircraft and those of less developed nations has grown ever wider.

In Iraq, they started with simple equipment and worked up to the F-16s they are now flying. The Iraqi forces had the advantage that they could read and write and that they had used complex aircraft before, but by starting with aircraft like the Cessna Combat Caravan, they achieved a workable, sustainable and effective capability without breaking the bank, or it’s collapsing under the weight of its complexity.

US Special Operations, on which some Special Operations Brigade are modelled, have long utilised relatively small fleets of light transport aircraft. These are now known as light tactical fixed-wing fleets, formerly known as non-standard aviation.

The Rangers and Special Operations Brigade need Air Mobility

Building a Special Operations Brigade Light transport Aviation Capability

The proposal is to enhance the capability of the Rangers in the British Army Special Operations Brigade, whilst offering a meaningful resource to special forces aviation, the defence engagement and capability building requirement, and even something for the conventional field army.

In this context, it means the Army Air Corps going back to a single squadron of fixed-wing light transport aircraft (and an aviation support squadron), and I don’t mean raiding the Historic Aircraft Flight!

The Army Air Corps moved their Defenders to the RAF, who then got rid of them. The RAF is getting rid of its C-130 Hercules and 146 aircraft, and not buying any more A400M, the latter of which are struggling for availability. Tactical transport for the Army is not in a good place.

None of this is the fault of the RAF, but it is a simple fact that our air transport capability is (for whatever reason) declining.

Rotary is in much better shape, the RAF has a relatively large Chinook fleet and is competing the Puma replacement at the time of this article. Both of these could provide the SOB with much-needed mobility and options for supporting the capability development element.

Rotary will always be in high demand for obvious reasons, it is costly to purchase and maintain, and often, beyond the capabilities of many of the nations, the Rangers will be supporting.

Start on the Ground.

The foundation is the support capability; the training pipeline, the engineering, the deployed logistics support and operations planning. It is these areas that would need to be resourced first, and I do not underestimate the challenge of bringing fixed-wing aviation back to the Army Air Corps.

Then go shopping (or at least building a business case)

This is not an exhaustive list, but three examples of the category, all of which are in service and currently in production. I have excluded new development aircraft and uncrewed designs, or older designs that might still be in use but are no longer in production, for example…

[EDIT: After the publication of this post, the MoD awarded an extension contract to Summit Air for parachute training]

Light Transport Aircraft — Single Engine

Single-engine economy, ease of operation in austere conditions and many years of service characterise the three examples. They are mature products with useful payloads of between 1,000 kg and 1,500 kg and an unrefuelled range of up to a thousand nautical miles (depending on payload)

The three also have an approximate purchase cost of £2.5 to £3m, although some of the more complex models will cost more.

All are adaptable to a range of roles from passenger and cargo transport, to basic ISR and medical evacuation.

Cessna Grand Caravan

Certainly, a bit of a legend, the Cessna Grand Caravan has been in service around the world for decades.

The Grand Caravan EX (EX standing for external pod) is the latest version, in civilian guise, it has a maximum payload of just under 1.5 tonnes and a maximum range of over 1,600 km. Payload and range are closely related, so with a usable payload of 900 kg, it can fly just under 900 km, between Warsaw and Tallinn in Estonia, for example.

It has seats for up to 14 passengers (snug) and a take-off distance of 430m, a float plane conversion is also available.

Although of passing interest for this article, in Iraq, the US and Iraqi forces made great use of the Cessna 208 Combat Caravan in the armed reconnaissance role, emphasising the undoubted versatility of the basic aircraft.

The Combat Caravan was designed and built by ATK and included an AAR-47/ALE-47 Defensive Aids System with composite armour panels for key areas. The ATK STAR mission system was integrated with a Wescam MX15D EO/IR sensor and a range of communication systems.

It was also developed to include Hellfire-guided missile firing capability.

The latest iteration of the Combat Caravan is marketed by Mag Aerospace as the MC-208 Guardian.

Their sales pitch is that in a low-cost single-engine aircraft, a user could ‘move seamlessly from ISR to CASEVAC/MEDEVAC to precision strike, eliminating the need for multiple aircraft types’.

One of the more interesting aspects of the design is the ability to strip it for air carriage.

One could easily imagine an A400M being able to transport two of these (at just under 3 tonnes), together with fuel and a couple of light vehicles with stores.

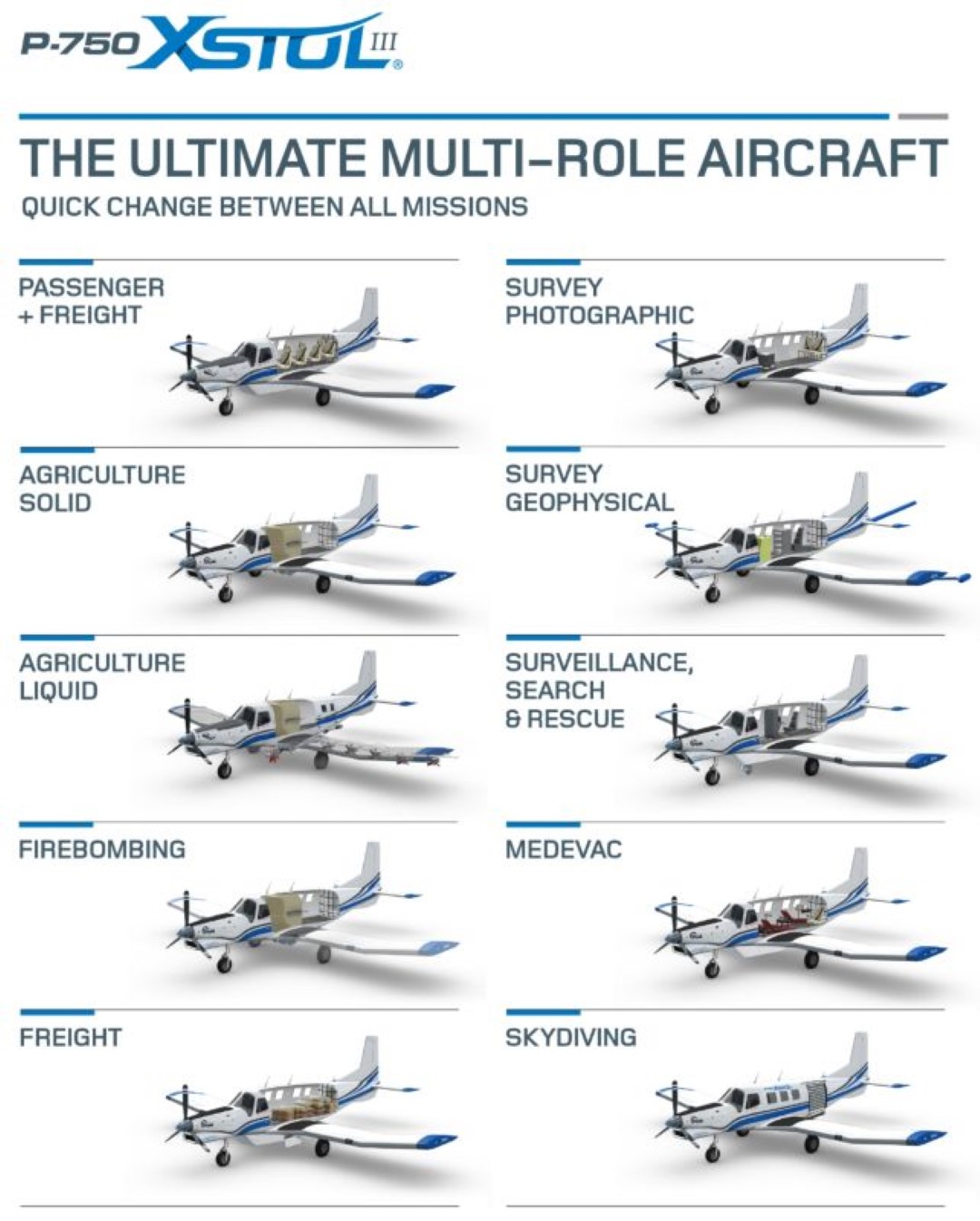

Pacific Aerospace P-750

The P-750 is marketed by Pacific Aerospace for operations in demanding locations where an extremely short take-off and landing are important.

At full load, the take-off distance is 220m at sea level and the landing distance is 166m

The video below gives some idea of performance (although it does look like an empty aircraft)

Pacific Aerospace also focuses on the adaptability of the P-750 in their marketing materials.

Not as mature as the Cessna, and certainly not as capable for armed ISR and other military duties, the P-750’s extremely short-field capability might compensate.

Kodiak Aero 900

The final example is the Kodiak Aero 900

The large cargo door allows small pallets to be loaded.

Britten Norman Defender

The Britten Norman Islander, built in the UK, represents somewhat of a unique performance space.

Payload and range are similar to the single-engine designs described above, but with twin-engine safety, hence me including it in the single-engine category as the fourth of three options :)

These incredible aircraft with such a long track record would be perfectly suited, and the latest ‘net-zero’ development is relevant as it would tie into the UK’s security objectives.

They are available with piston engines for simplicity and low maintenance, or Rolls-Royce turboshaft engines for greater performance. The Islander can be quickly re-rolled for passenger, cargo or Medevac.

The Defender variant has been in service with both the Army Air Corps and the Royal Air Force in the past.

Light Transport Aircraft — Twin Engine

Moving to a twin-engine design generally affords greater safety (especially for overwater routes), and improved performance and carrying capacity. From a military load perspective, the twin-engine designs have much greater utility, although that also arrives with a more expensive price tag.

As above, three examples…

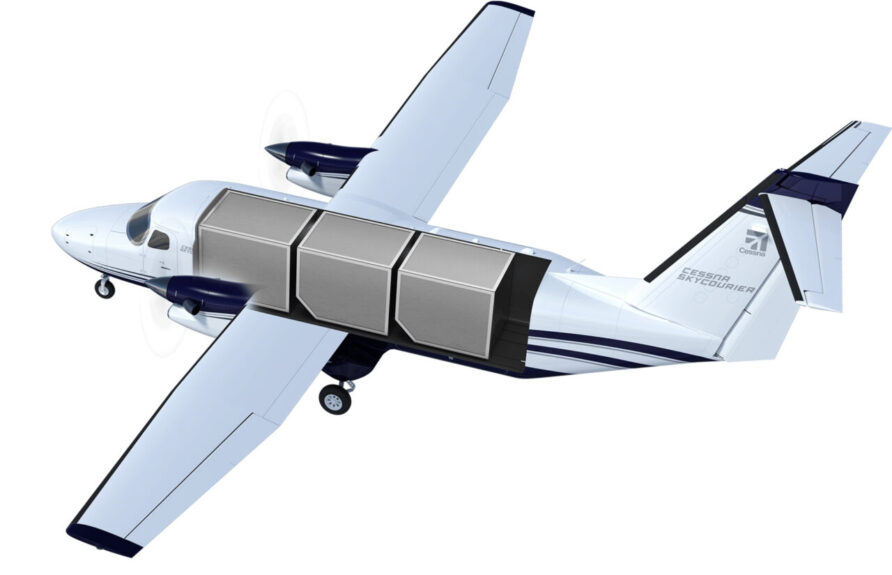

Cessna Sky Courier

Back with Cessna, the Sky Courier is a relatively new aircraft.

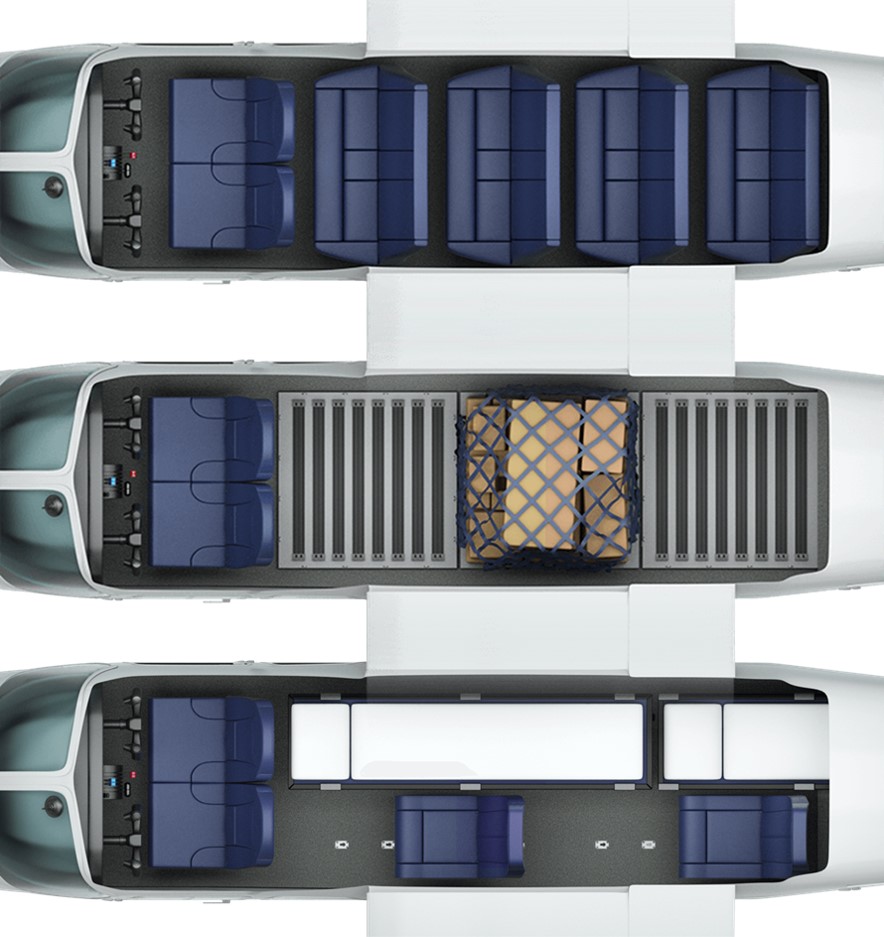

Although there is a 19-seat passenger version, the Sky Courier is really optimised for high-frequency operations moving freight. The square-section fuselage and large cargo door (2.2m wide by 1.8m high) maximise compatibility with standard aircraft LD3 containers and a cargo compartment of 25 cubic metres.

The aircraft has a maximum payload of 2.7 tonnes and although it does not have a rear cargo ramp, the large door, square section and roller floor could accommodate a range of small tactical vehicles. The range is slightly lower than some designs above, at 750 km, and the takeoff distance is 1,000m.

Sky Courier is clearly aimed at high-efficiency operations between established freight hubs with handling equipment, optimised for low-weight high-volume parcels.

They cost approximately £7m each.

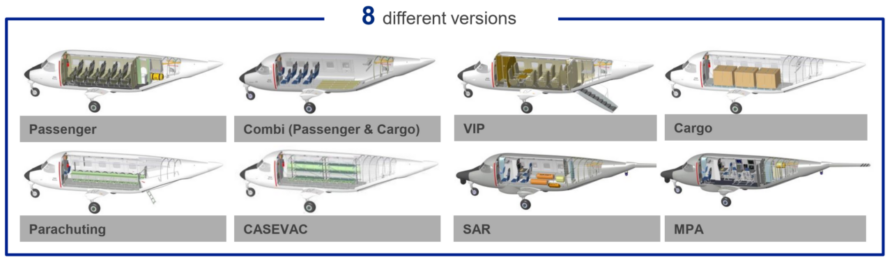

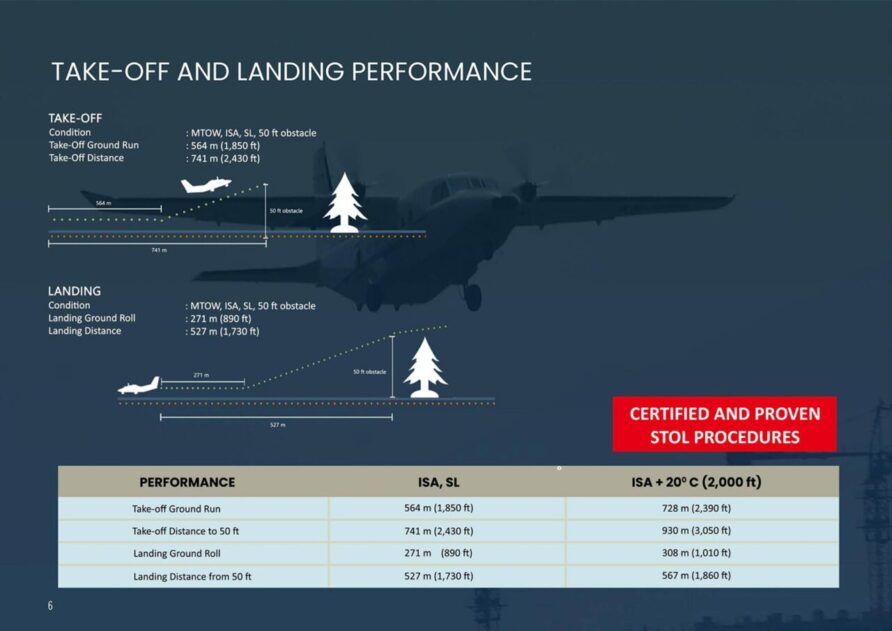

PZL M28 Skytruck

From the Polish manufacturer, PZL Mielec, the M28 has a slightly lower payload than the Sky Courier at 2.3 tonnes and 14 cubic metres but is perhaps more suitable for military applications.

The aircraft has two Pratt and Whitney PT6A engines and a take-off distance of 550m and a landing distance of 500m.

Built for harsh conditions, it can operate on unprepared runways and at +50 degrees C to -50 degrees C. The maximum range is 1,600 km with 19 passengers.

Like the other aircraft described above, the manufacturer emphasises the multirole capability

The most useful configurations in this context would be the combi, medical evacuation, cargo or parachute, marketed by Sikorsky

The combi configuration could carry 9 personnel and their equipment (cargo can be in front of or behind the seats).

Although the cabin width is 1.73m wide, the rear door is narrower at 1.2m (height is 2.6m).

This would limit options if a vehicle was required to be carried, options would include motorcycles, a quad bike, Ski-Doo or small ATV like a Honda Foreman.

The M28 does not have a vehicle ramp, so any small vehicle would have to use external handling equipment or the integral 500 kg winch

Like the Cessna Grand Caravan, defence integrators have developed a range of armed ISR options, the latest version being the Sierra Nevada Corporation MC-145B Coyote.

The Coyote has all manner of optional extras, from Hellfire and APKWS to BLOS satellite communication systems and a full DAS fit. (the tube-launched UAS in the video above is the same as described in this post, the Coyote, confusingly!)

It is very much a military aircraft.

With a price tag to match.

Indonesian Aerospace NC 212i

Like the M28 (with a heritage going back to the Antonov AN-28), the NC212i has an equally long heritage going back to the Casa Aviocar C212 in Spain.

NC212i is a developed version of Casa C212-400, with over 100 now in service.

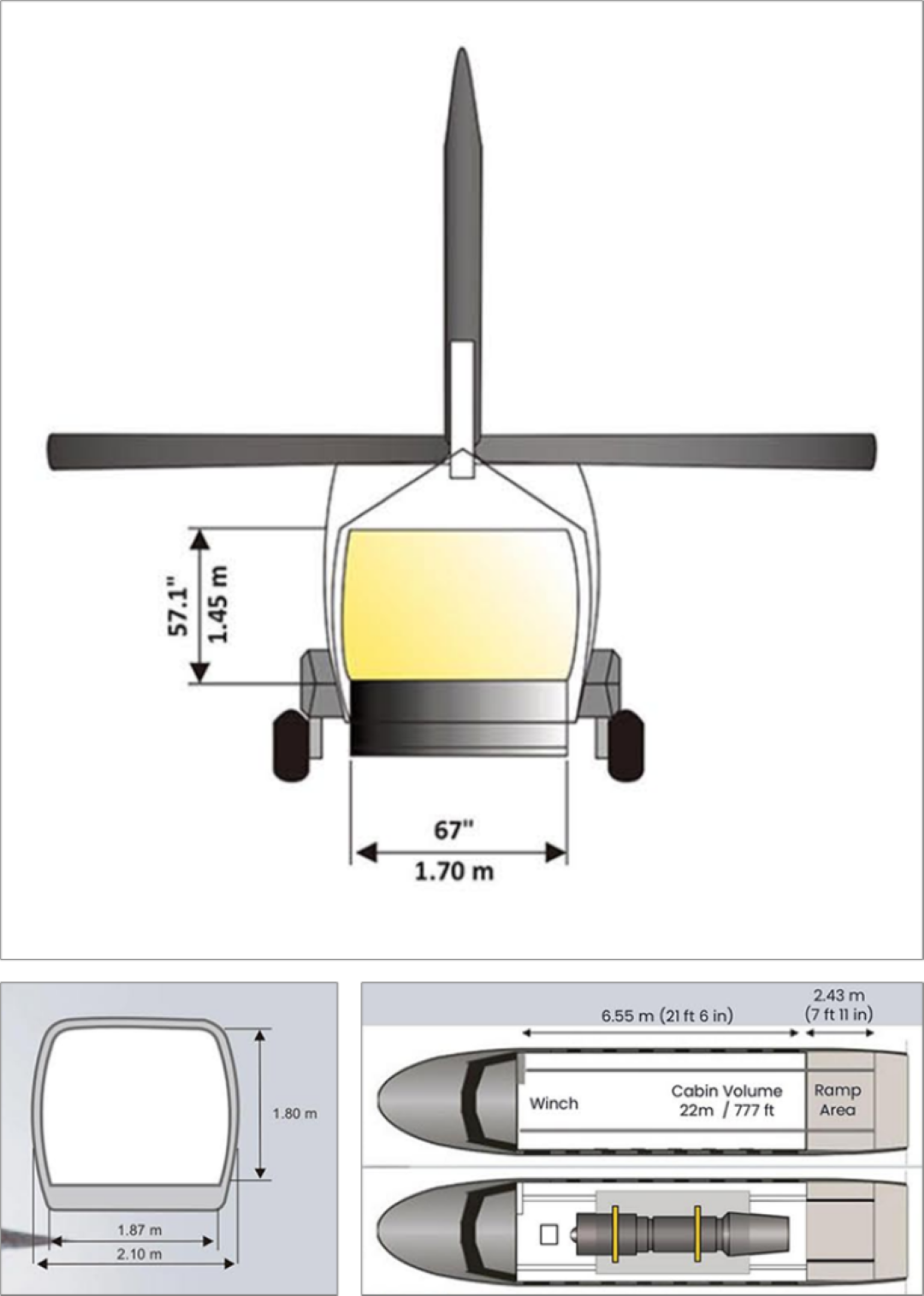

The NC212i has a 3-tonne payload and 22 cubic metre cargo hold, slightly smaller in volume than the SkyCourier but with an extra 300 kg payload.

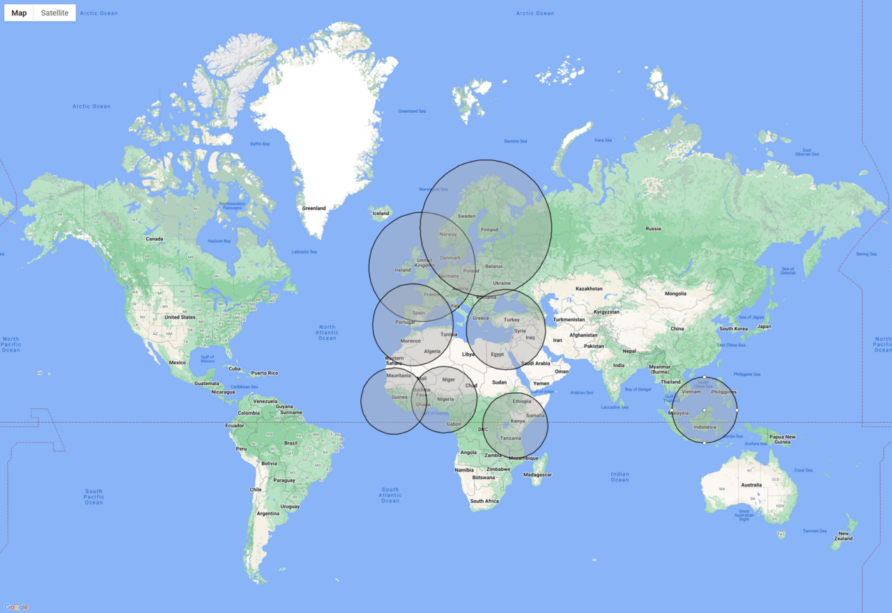

With a 2-tonne payload, it has a range of 800 nm. The map below shows that 800 nm from Brize Norton, Talin, Abuja, Freetown, Nairobi, Akrotiri and Bandar Seri Begawan. These are not round trip ranges, the aircraft would need refuelling at the other end, so they are not would normally be considered a combat radius, but a useful illustration nonetheless.

Although the headline performance figures of the NC 212i and Sky Courier appear similar, the former retains the rear cargo ramp of the C212.

Unlike the M28, which has narrow rear doors and no ramp, the NC212i has a 1.7m wide ramp, this opens up a much broader range of vehicles than the M28 and derivatives.

The only practical option for the M28 is a quad bike or motorcycle, but the NC212i could easily carry vehicles like a three-axle quad or small ATV.

As with quad bike ATVs, the large volumes and supporting ecosystem of manufacturers and integrators work in favour of defence markets.

Manufacturers include Polaris, Bobcat, Yamaha, John Deere, Honda, and Tracker. Sizes and capacities vary with some focussing on load bed space and others replacing that with seating, long and short wheelbase variants are commonplace with most of the manufacturers.

The C212 is a proven aircraft for air despatch and parachute delivery.

Indonesian Aerospace has also developed a new aircraft called the N219 that is more akin to the Sky Courier.

The NC212i costs approximately £8m, including a spares package, slightly more than the Cessna SkyCourier.

Weapons and Sensors

Instinctively, I am not drawn to the value of adding many weapons and sensors.

Weapons add significant cost, integration and support challenges, and they put an aircraft type not designed for combat into a combat environment.

If the situation requires air-delivered weapons, deploy an Apache and accept the cost.

Sensors and BLOS communications would also add to costs, but all the examples shown have been operated with additional equipment, does our conservatism result in over-estimating the challenges? Many of these sensors and communications systems are no longer the sole preserve of defence, they are now widely used not only by Government organisations but in commerce and industry.

Again, though, if we really need advanced sensors in the air, there is a world of modern and cheap UAS to look at.

One option that, I think, would be worth considering is a podded sensor.

A few of these don’t even need power from the aircraft or even data cables. Control and feeds from the pod and its sensors are relayed to an operator in the aircraft by Wi-Fi, resulting in very low integration costs.

The 100 kg SCAR pod from Airborne Technologies even has a self-contained three-hour battery.

It can be fitted with pretty much any sensor on the market, including the same Thales i-Master radar as Watchkeeper

From the manufacturer

This Pod is completely self-sufficient and allows wireless operation. Data connection from pod to operator station is done via WIFI and needs no external cabling. The use of an internal – easy changeable – battery pack grants power supply for up to 3 hours.

The S.C.A.R.-Pod does not need any airframe modifications on the aircraft. The lug suspensions enable immediate use on every aircraft with hard points. The light weight carbon fibre pod carries a complete surveillance mission architecture which upgrades any aircraft to an ISR platform in less than 1 hour.

It offers room for an EO/IR Gimbal, Downlink, Uplink, Moving Map, Augmented Reality System and COMINT/SIGINT equipment. With this new S.C.A.R.-Pod every aircraft and helicopter equipped with hard points can be a surveillance aircraft instantly.

Logos Technology also offers a range of very advanced podded systems.

Good comms and navigation systems would be a must-have, and these might drive up costs if options beyond the standard commercial fit were required.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Summary and Thoughts

With unfunded requirements across defence, it is difficult to justify spending on what is, in reality, a niche requirement.

I get it.

But if the British Army is to make a success of its Special Operations Brigade, I think it needs mobility on the ground and in the air.

Re-establishing an Army Air Corps fixed-wing aviation capability would not only provide this extra capability to the Rangers, but it would also offer something to the wider field army, and special forces aviation and play an important role in the wider defence engagement activity.

Can we afford it, can we especially afford it when the RAF is having to make very real cuts to air transport capability?

If we found some cash down the back of the sofa, would it be better just to spend it on what we have?

I cheekily asked on X (formerly known as Twitter) if anyone would swap a Chinook for a squadron of Cessna Grand Caravans and whilst it was obviously provocative, my point was not about the obvious differences between those two aircraft, but how we spend finite defence budgets.

A 12-aircraft squadron of the single-engine basic types would be less than £40m to purchase, and they are certainly frugal to operate. Pilots and maintainers would, of course, be an additional cost, but are there creative ways to cover this, contractor support, sponsored reserves etc.?

I have written many times about small niche fleets being easy prey to rapacious defence reviews, I have written equally prolifically about the dangers of ignoring Defence Lines of Development (DLOD) when looking at the sticker prices of equipment, but there are still good arguments to be made, even if one acknowledges the difficulties and hidden costs.

For what it is worth, I think a squadron of light transport aircraft would be transformative for the Special Operations Brigade, have utility in the wider Special Forces community, and utility across more conventional areas like parachute training and small-scale logistics and personnel transport.

Especially if we can operate them at a higher risk threshold, as the Rangers are based on.

What do you think, see you in the comments?

PS

If I was General for the day, it would be half a dozen grand Caravans and half a dozen NC212i’s, am not convinced by the ‘all option extras ticked’ approach of some others.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Fixed wing should be same size as Chinook

Belgium plans to acquire a squadron of light STOL utility aircraft to support the Special Operations Regiment. This could be an example.

Some of these could even land on the QE Class…

Interoperability boone?

Real pity that Shorts stopped making the 330.

From current options, its the B-N Defender for me; its not as though we dont know how to operate and support it. And a left field option might be the V12 Diesel engined conversion of the DH Beaver: https://flyer.co.uk/reds-v12-turbodiesel-to-power-beaver-conversion/

Jumping form single engined to twin

… and jumping over this one in the same go?

governmentprocurement.com

https://www.governmentprocurement.com › news

May 29, 2024 — The U-28A stands out in military aviation for its smooth transition from a civilian aircraft, the Pilatus PC-12, to a key asset in special operations.