Soviet Russia produced a range of huge transport helicopters that broke many records, most of which stand today. This lineage culminated in the Mil-26 that is still in service.

The internal market for heavy-lift helicopters was shaped by the need to move vehicles and large amounts of equipment used to develop the wilderness areas. Soviet military forces were also keen to use them for air assault and air transport operations, and especially for the Strategic Rocket Forces.

Yak-24 (Horse)

Although the pre-war YU-2 project was never developed, the wartime OKB-3 saw very limited development, and several other projects never came to fruition, the first heavy-lift helicopter to see series production was the Yak-24.

The Yak-24 tandem rotor design made its first flight in July 1952.

The design actually comprised two Mil-4 engines, rotors, transmissions, and control systems, joined by some components from a Yak 14 fuselage. Its rather ‘industrial’ look, earned it the nickname the ‘flying truck’. Like the Bristol Belvedere and H-21 Shawnee, the tandem configuration allowed all the engine power to be devoted to thrust and lift.

By 1952, the Yak-24 (Horse) was in full production at Leningrad’s Plant 272 and in 1955 set many payload records that Russian helicopters would continue to break over the following years. The first production models had a V tail fin, but this was replaced with a different configuration. Variants included VIP transport, pipe laying, passenger, and even a flying film studio. With two АШ-82В 1430 hp engines, the improved Yak-24U could lift a payload of 4 tonnes with a maximum range of 265 km.

The VIP transport variant (Yak 24K) is shown below.

A widened version was also developed but by 1959, the much more effective Mil-6 was in production and Yakovlev ceased helicopter development and production.

Mil MI-6 (Hook)

The Mil-6 (Hook) was produced at two factories; No 23 in Moscow and 168 in Rostov on Don, with over 900 being eventually produced. Variants included passenger, survey, radio relay, tanker, ASW, command post, aerial minesweeper towing, laboratories, and most importantly, strategic rocket carrier.

The prototype first flew in 1957 and after a short test period entered production in 1960, the final production quantity exceeded nine hundred.

In 1962, it smashed records with a 20-tonne lift at a maximum take-off weight of 48 tonnes. In comparison, the very latest CH-53K, yet to enter service with the USMC, has a maximum payload of 16 tonnes and a maximum take-off weight of 38.4 tonnes.

Passenger carrying capacity was 90, or 70 paratroopers. In the medical evacuation role, it could carry 41 stretchers and 2, busy, medical personnel. The maximum speed was 300 kph with a range of 620 km and a maximum ceiling of 4,500m. The two Soloviev D-25V (TB-2BM) engines each produced 4,100 kW (5,500 SHP). The rotor was a five-bladed design and the internal cargo capacity was 11.34 tonnes. Everything about the Mil 6 was built tough, even the engine access doors could be folded out and used as a work platform for maintenance engineers.

Read more (Amazon Affiliate Link)

The large clamshell doors provided easy access for vehicles and stores and a roof-mounted crane could be used for loading and unloading. The Mil-6 Hook delivered approximately double the cargo weight and internal volume of a Chinook and not far off two-thirds of a C-130 Hercules.

Production ended in 1980 and during the period, several variants were produced;

- Mi-6PZh fire fighting

- Mi-6PS search and rescue (SAR)

- Mi-6APS improved Search and Rescue

- Mi-6TZ-SV mobile vehicle tanker

- Mi-6M Anti-Submarine Warfare

- Mi-6P passenger

- Mi-6S Medevac

- Mi-6VKP command post

- Mi-22 Hook C-Command Post

- Mi-6AYaSH command post with SLAR

It was no doubt, a successful design, perfectly aligned with military and civilian requirements, especially the Soviet Cold War air assault doctrine.

Mil MI-10 (Harke)

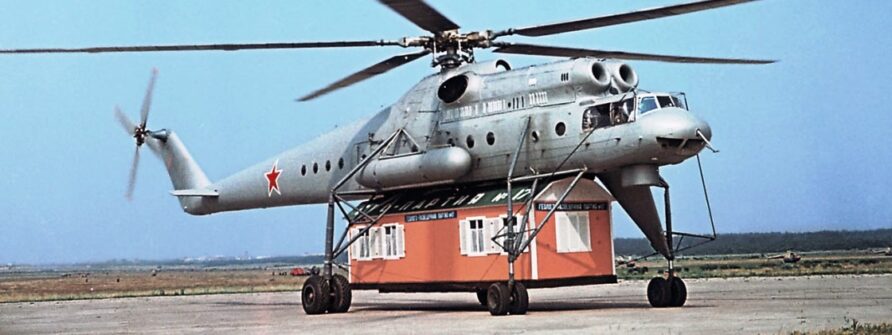

The Mil-10 (Harke) took the Mil-6 and converted it into a flying crane configuration.

It was designed to carry outsize cargo without resorting to a flexible sling, instead, an underslung rigid platform or special lifting attachments meant long lifting slings could be dispensed with. Fitting the platform only took a couple of minutes. The Mi-10 entered service in 1963 after the prototype flew in 1960.

It set a record of 25 tonnes to lift in 1965 with a specially modified P variant that had aerodynamic fairings for the undercarriage, although the normal payload was 15 tonnes.

The short-legged version, Mil-10K, was also used for developing oil fields and has a lift capacity of a couple of tonnes higher than the standard variant. It also had a load observer station beneath the fuselage.

Video

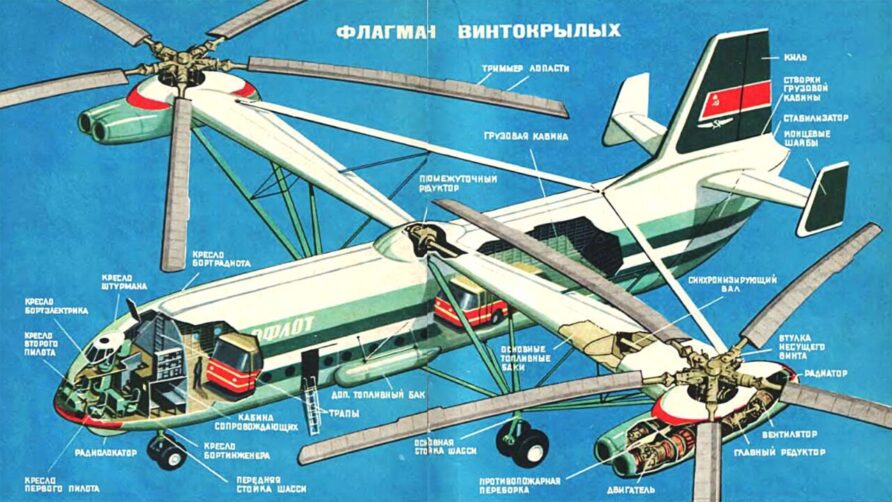

Mil MI-12 HOMER

As vehicle and missile systems’ weight grew, especially the UR-500 and SS-8 ICBM’s, the need for even heavier lift helicopters resulted in some alternatives to the single rotor design.

The V-12(Mi-12) and V-16(Vi-16) were developed with a side-by-side rotor arrangement, with the V-16 having a rotor at the front of the fuselage.

The V-12 had the same cargo hold dimensions as the AN-22 transport aircraft (approximately 28m × 4m × 4m) and used two Mil 6 engine and transmission systems mounted at the end of each inverse tapered externally supported wing.

The V-12 (Homer) first flew in 1967 and in 1969, a record-breaking 40-tonne lift was successfully carried out.

As testing progressed, the development of the larger also V-16 commenced. Despite initial success, only two prototypes of the V-12 were built, and it failed to enter production, the V-16 was also cancelled.

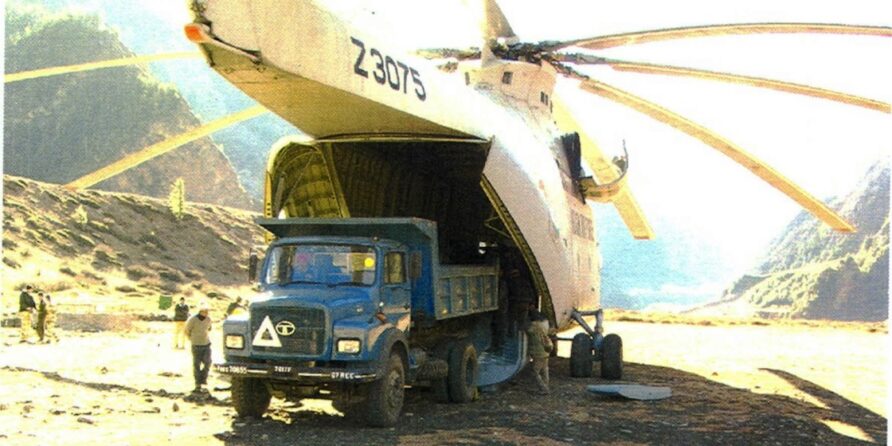

Mi MIL-26 (HALO)

By the time the V-12 was cancelled, the Soviet Strategic Rocket Forces had started to gain greater experience with railway-mounted systems. Engine development and the death of the designer meant that work ceased, and fewer AN-22s were also ordered due to a similar change in ballistic missile transport requirements. Instead, a new single-rotor design would be developed, the Mi-26 Halo.

The Mil 26 (Halo) was intended to move 20-tonne payloads over 500 km and, in simple terms, is a larger Mil 6. Development work started in 1971 with the first flight in 1977. It entered production in 1980 and military service in 1983. Although it is not much heavier than Mil 6, its payload is 20 tonnes, but a 1982 record-breaking lift demonstrated a lift of 56 tonnes to an altitude of 2,000m.

Landing gear height can be adjusted for ease of loading and unloading, and the cargo hold is equipped with an overhead gantry crane and two internal winches. It retained the ruggedness of the Mi-6 but was larger and had a higher payload, roughly the same as a C-130 Hercules. With blades turning, it is approximately 40m long, 10m longer than a Chinook. The cargo hold dimensions are 12m long, 3.3m wide, and 2.9 to 3.2m high.

A civilian variant commenced production in 1985 and a ‘flying crane’ Mil 26K was developed but never entered service.

The Mi-26MS is a medical evacuation variant and the Mi-26TZ is a forward tanker variant with additional internal fuel tanks, pumps, and hoses. Others include radio relay, firefighting, and command post.

Over 300 have been built and the latest version, available from Rostvertol, is the Mi-26T2. This has modernized avionics and a glass cockpit, digital autopilot, and other enhancements that mean it can be operated with a crew of two instead of five.

This document, from NASA, provides a good comparison between Russian and Western helicopters but it is interesting that Western forces have not developed anything with the same lift weight and volume capacity as the Mil 26, and there is nothing in the pipeline either.

One cannot fail to be impressed with the large Russian heavy-lift helicopters.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The secret of their success is in the gear box engineering so I believe!