This series began with a discussion about the necessity to minimise resupply vehicle movements between echelons, considering the potential prevalence of FPVs and UAS on a modern battlefield.

Personnel in static or semi-static positions will require resupply, but resupply vehicles will be under constant threat up to 20 km behind the forward positions.

Should we adopt a static mindset, or should we continuously consider manoeuvre to avoid being fixed in place? This is a reasonable question, but it does not change the premise of this series.

Effective counter-UAS measures and uncrewed vehicles, both aerial and ground-based, are the obvious solutions, as evidenced by their use by both combatants in Ukraine.

That said, given the relatively slow pace of adoption of these systems by NATO forces, the conversation turned to practical measures that can be implemented quickly, and by quickly, we meant cheaply.

With this in mind, this series looks at the problem from both ends, demand reduction, and improving existing vehicle efficiency

Demand Reduction

Demand reduction is the most obvious first step, use less stuff and less stuff has to be transported.

Commodities that have to be moved include water, food, medical supplies, ammunition, defence stores, in some cases fuel, and in others, charged batteries.

Vehicle Efficiency

For that residual demand, reducing the number of vehicles moves by making any one vehicle carry more, by definition, decreases the number of times that vehicle has to move.

This is all about risk reduction in the near term

Until we have AI controlled cargo drones and UGVs in service with the Field Army, the Field Army will have to make do with its existing vehicles, from an e-bike to a MAN SV truck.

Every truck roll and every quad move, will have risk, we need to think how to reduce that risk.

The rest of the series will look at these in turn…

Echelons

I mentioned the echelon system above but thought an edit to add an explanation would be useful.

In the British (and pretty much all other NATO nations) Army , units are organised into a logistic echelon system to provide layered support for operations.

- F Ech

- A1 Ech

- A2 Ech

- B Ech

At the front, the Fighting (F) Echelon engages in direct combat with enemy forces.

The Administrative (A) Echelon provides immediate or short notice support to the F Echelon, primarily for resupply, transit and maintenance, in contested areas.

A Echelon is further split into A1 and A2.

The A1 Echelon provides close, subunit level support (e.g., company-level), typically commanded by a Company Quartermaster Sergeant (CQMS) and focused on immediate commodities push-forward.

The A2 Echelon is the battalion-coordinated portion of this support, consisting of the remaining forward-deployed personnel, vehicles, and equipment needed for day-to-day resupply, repairs, maintenance, and recovery of the F Echelon. A2 operates in the forward area but behind A1, ensuring sustained logistic flow, i.e. A2 resupplies A1, and in resupplied by B

The exact composition, vehicle type and use of A1 and A2 can vary by task, unit type (e.g., light role infantry or armoured infantry), and scenario, but it emphasises flexibility in planning.

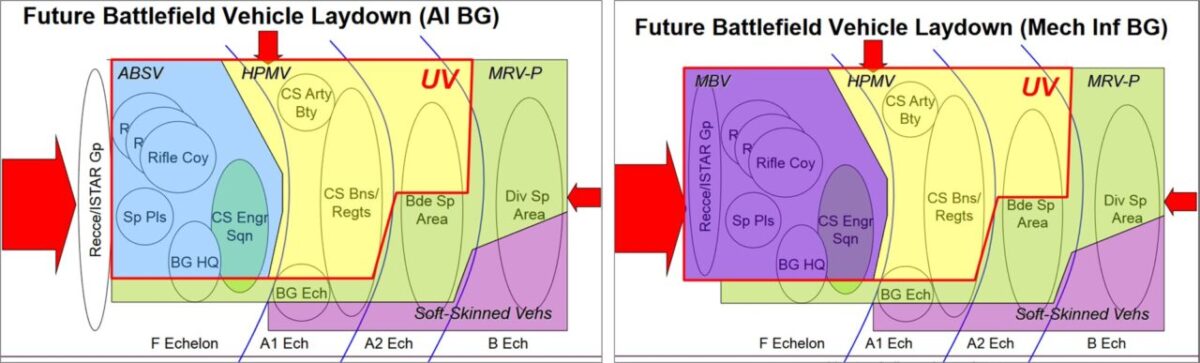

The diagram below, although a few years old from the now cancelled Multi Role Vehicle (Protected) programme, provides a good illustration of the vehicle differences between unit type, despite using the same general concept.

The Base (B) Echelon is the rearmost, maintaining workshops, holding longer-term stores, and aggregating bulk unit stores.

The organisation and composition of each is flexible enough to adapt to changing situations, but fundamentally, each support each other, and each must be integrated.

None of the units within any echelon have ever been considered to be safe from enemy observation and attack

With the widespread availability of armed drones and FPV’s, some with considerable range, it is probably fair to say that the physical distances between echelons might have to be re-evaluated.

I’m arguing for two (leapfrogging) corps-level support clusters with their own protective umbrella (especially air defence, but also SatNav jamming, X-band jamming), where civilian vehicles drop off containers and diesel.

Military 8×8 then move such goods mostly on demand towards brigade drop-off points (multiple hidden caches). Units move thier own vehicles to those places to pick up what they need if possible, battle taxis (APCs with 1 crewmember, UGVs and multicopters) shuttle to units in contact.

A tank Bde during mobile warfare should carry a lot, and receveive goods directly from corps-level 8×8 supply vehicles (partially to carry on its own bulletproofed 8×8 vehicles).

Let’s not focus entirely on static frontlines. A conflict NATO vs. RUS&PRC would not be much about static frontlines in Europe.

Howitzer ammunition accounts for almost half the supply at battalion/brigade levels. Mortars add a noticeable burden at battalion and company.

I wonder how much the logistical throughput and vehicle count in the middle distance could be reduced through changing to long range guided rockets as an entirely logistics-focused perspective. The Americans used to say why send a man against a foxhole when you can send a bullet. Well, why send a man hauling shells down an open road to cannons when you can ship the warheads by rocket from the rear to the target?