The high north represents an extreme challenge to operational mobility and although the British Armed Forces have the capability in this area with the Royal Marines, their changing role may precipitate an emerging requirement for the British Army.

The High North was a term coined by Sverre Jervell, a Norwegian diplomat, in 1986 in a book called The Military Build up in the High North.

Although not defined in the book, it has subsequently been used to describe an area that spans the Arctic (a clearly defined area) and includes references to both climate and geography. For example, a climate definition is those areas to the north of a line with a specific median July temperature, others include an area to the north of the southern limits of maximum sea ice or the tree line. The Arctic Council Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) uses a hybrid definition based on multiple factors.

The term also has a clear political aspect, and the Norwegian Government a few years ago attempted to put it in context.

The High North is a broad concept both geographically and politically. In geographical terms, it covers the sea and land, including islands and archipelagos, stretching northwards from the southern boundary of Nordland county in Norway and eastwards from the Greenland Sea to the Barents Sea and the Pechora Sea. In political terms, it includes the administrative entities in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia that are part of the Barents Cooperation.

A Defence Select Committee report, also a few years ago, had this as its working definition;

‘European Arctic’, roughly stretching from Greenland in the West to the Norwegian/Russia border in the Barents Sea in the East, and encompassing areas of strategic importance such as the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) Gap and Svalbard.

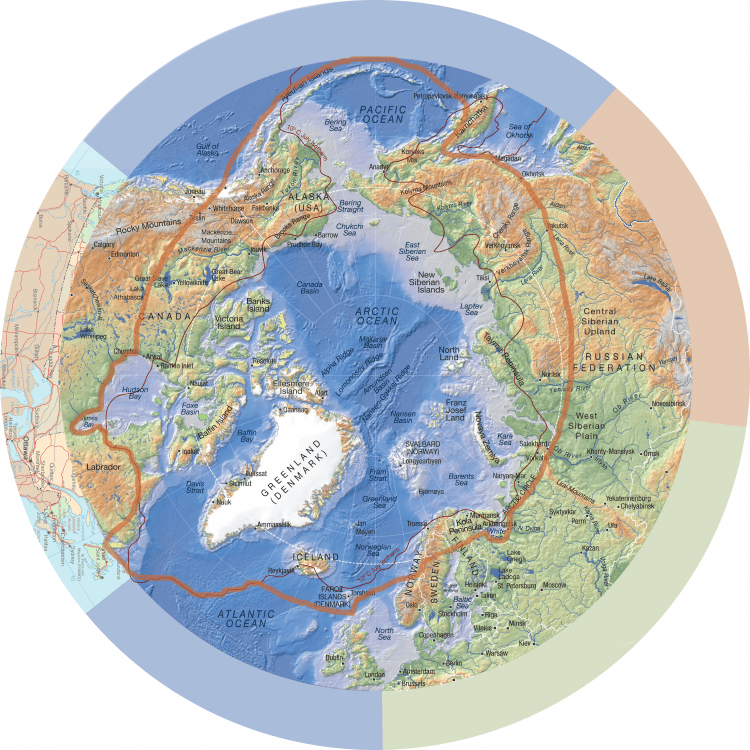

Whilst the definition of the Arctic Circle is bounded by geography, the concept of the ‘high north’ is less so, this hasn’t stopped people from trying to map it, one example below

China achieved ‘observer’ status on the Arctic Council in 2013 and Russia has been a long-standing member. Both are hostile to our interests and that of our allies. The UK has also been an observer since 1998 and although the Arctic Council was originally intended to avoid matters of security, it is difficult to see that enduring.

Climate change may result in a reduction of Arctic ice, and this will inevitably result in greater access and economic exploitation. This exploitation will likely result in increasing political tensions with the potential for conflict.

The fact remains, whatever the definitions, it is on our doorstep and includes friends, allies and potential enemies.

The Select Committee report concluded;

As the ‘globalisation’ of the region continues, an increasing number of states which are more geographically distant from the Arctic are declaring that they have an interest in Arctic affairs and wish to share in the benefits which might come from a more accessible Arctic. This is to be welcomed, as long as these interests continue to coincide. We should nonetheless be aware, in this new age of ‘great power competition’, that this state of affairs may not last indefinitely. The Government should work closely with allies to establish a common position on all aspects of international law in the Arctic to ensure that disputes active amongst states in the region are not aggravated or exploited

The UK could simply rely on the Royal Navy/Royal Marines and Royal Air Force, and her allies in the High North, or the British Army could take a greater interest in the area. Everything has a resource implication, more training and equipment spending for the high north means less elsewhere, but my view is that a modest tilt to the North would not be a bad thing. The Army Air Corps and selected units do engage in regular training for Arctic operations but other units much less so.

If the Army does, one of the many things it will need to consider is that of mobility, especially on the ground. The terrain in the high north is incredibly complex and varied, it is not just deep snow in the winter and mud in the summer, but what characterises them most is their very low bearing strength. This means conventional high-pressure tyre vehicles are not suitable, tracks and big fat tyres are the norm.

Existing Vehicle Mobility Equipment and Programmes for the High North

The obvious answer would be for the Army to simply purchase a few BVs10 Vikings, as in service with the Royal Marines. The protected Viking (BvS10) can also be carried as an underslung load by Chinook.

The Bv206 is an extremely versatile tracked articulated amphibious vehicle with a ground pressure of less than 14kPa/2PSI, highly mobile. The basic vehicle weighs approximately 4.5 tonnes with a maximum payload of 2.2 tonnes or 12 personnel and their equipment and can be an underslung load for Chinook. It can also be carried on the LCVP Mk5.

The Royal Marines Bv206D is generally used for non-protected mobility tasks, logistics, mortar carrier and communications, they are exceptional machines with a very long pedigree, but will eventually need replacing. Replacement programmes seem to have come and gone with some regularity, but given the market size, and active integrator market, difficult to see this happening.

Or even their Oversnow Reconnaissance Vehicles (ORV). Centre drive single track snowmobiles are available in sports and utility models from several manufacturers. The newer Royal Marine models seem to be the BRP Lynx/Ski-Doo Expedition which is 3.4m long, 1.14m wide and 1.33m high, weighing in at approximately 400 kg. They are powerful machines designed for high speeds over deep snow, much more efficient than a quad bike ATV with a track kit.

The British Army could also join the US Army Small Unit Support Vehicle (SUSV) replacement programme that is currently trialling the BAE Beowulf and Oshkosh/ST Engineering Bronco 3 articulated tracked carriers.

Beowulf is an unarmoured version of the BVs10 that can carry an 8-tonne payload split across both forward and rear cars

The Bronco 3 (Oshkosh Cold Weather All-Terrain Vehicle) is the latest development of the mature Bronco platform, with a greater range and payload.

Both are comparable designs.

Both vehicles are required to be fully amphibious (up to 300 mm wave height) and available in four variants; general troop transport, cargo, emergency transport and command and control.

This would not be a Think Defence post if it didn’t look beyond the obvious!

Mobility Alternatives — Lightweight Vehicles

Assuming that ‘lightweight’ means anything that can be carried as an underslung load by in-service Support Helicopters, an upper weight ceiling of around 8–10 tonnes would be required. For use in cold environments, tracks can also be fitted, again, it might be worth trialling these against conventional snowmobiles for cold weather use, Matracks are the market leader, although there are others, such as Camso.

Any small ATV can usually be fitted with after-market track kits, ski-equipped trailers are also available. For light role forces, simply adopting these would provide additional mobility for some solid and snow conditions without purchasing entirely new vehicle types.

The Canadian Alltrack AT-20HD has a kerb weight of just over 2,700 kg, but with a payload of nearly 1,600 kg, has a gross weight of 4,309 kg.

I have included it here as an example, as is the UK-manufactured Loglogic Softrak 75, one of which is actually in use as an MoD range vehicle. It has a kerb weight of 2,550 kg and a payload of 2,000 kg, with hydraulic and hydrostatic power take-off should it be needed.

With a top speed of 16 kph, it would take some to cover any distance but with a ground pressure of less than 2PSI, its terrain accessibility is excellent.

It can use a tracked or wheeled self-loading trailer and is available in a couple of larger sizes. The load body can be replaced with a tipping body or 8-seat crew pod (in addition to the three seats in the cab).

It can also be fitted with a demountable cargo module, akin to a manual DROPS style arrangement.

The larger AT-50HD weighs 3.8 tonnes and can carry a payload of 3.2 tonnes, two NATO ammunition pallets in a basic vehicle that can be sling-loaded by a Merlin (or two with a Chinook) and carried internally in either. The largest model, the AT-150HD can carry a 15-tonne payload in a footprint no longer than a BV206, it can also be internally carried inside a C-130 Hercules without preparation. These are exceptional machines.

Another small tracked carrier is the 8-seat Pioneer from UTV Canada. At 8,000 kg gross weight, the UTV Achiever RT-04 has a 4,000 kg payload, just one example from many available might need some insulation, though!

Other manufacturers of tracked all-terrain vehicles for use in demanding terrain include Lynx Technologies, Gilbert, Prinoth, UTV, Fecon and Power Bully.

AEBI make a range of lightweight high-mobility vehicles, the VT450 for example. These are versatile vehicles that generally fall under 10 tonnes of maximum weight and all have multiple tool attachment options such as loading jibs, tipping bodies and hook lifts.

For snow and soft terrain, they can also be fitted with tracked wheel replacement units.

What characterises all these designs is a complete lack of protection, instead, they focus on mobility and payload, as might be expected for civilian equipment. These could easily be converted to military use, although their mobility would likely be lower than the established twin-car articulated designs.

And how could I not mention the famous Sherp, shown in the video below with a trailer system called the Ark

The Ark, a powered personnel-carrying trailer, has a capacity for 22 personnel or 1,600 kg.

Other versions in the concept stage include medical, cargo and tanker variants, the latter two able to carry a payload of up to 3,400 kg.

Certainly, interesting vehicles.

Mobility Alternatives — Medium to Heavyweight Vehicles

Beyond the carriage of small numbers of personnel and modest cargo, larger vehicles might also be used, especially for containers or container-sized loads. The Army’s Sky Sabre air defence missile defence system is one such notable example.

This uses a modified 20ft (ca. 6 m) ISO-compatible flat rack, there is no way it can be carried by either a Bronco or Beowulf-type vehicle or any vehicles described in the section above, something larger is needed. Although several vehicles from Prinoth and Alltrack can have considerable payloads using a single-tracked carrier, up to 20 tonnes in some cases, the payload area is not quite as large as required for a 20ft (ca. 6 m) ISO container. Unless we intend to purchase from the Russian Federation, the only alternative is Canada and the US, which have some manufacturers of vehicles used in the oil exploration, pipeline and mining sectors.

One such example is Foremost

The wheeled portfolio includes the Delta 2 and 3, two or 3 axle centre-frame steered vehicles

The Foremost Delta 3 is a versatile all-wheel drive, terra-tired transporter. Utilizing proven powertrain components and heavy duty center-frame steering, this high floatation vehicle provides economic transportation of payloads up to 15 tons. The Delta 3 provides superior off-highway mobility and can be readily adapted for all chassis-mounted equipment. It is ideal for logistical support of remote drilling operations, pipeline and powerline construction and maintenance, or other specialized projects faced with travel through marginal terrain conditions.

With a 13.6-tonne payload, the Delta 3 (pictured below) has a ground pressure of 7.5 PSI, about the same as a person.

Commander C and Tri-axle increase both payload and load-bed space, up to 36 tonnes

Difficult to see the military application for the very large C and Tri-axle, perhaps as a prime mover for the construction plant.

For even better mobility in deep snow and muskeg/bog soils, large tracked carriers are also available from Foremost. At the bottom of the range is the Nodwell 11/240, similar to many in the previous section, the slightly larger Nodwell 320 has a payload of 25 tonnes and a deck length of 6.9m, big enough for a 20ft (ca. 6 m) ISO container.

An unpowered tracked trailer is also available for the Nodwell range.

The Chieftain R is an articulated centre steer tracked carrier with a payload of up to 13.6 tonnes, but the much larger, non-articulated, Chieftain D and Husky 8 are the top-of-the-range vehicles with high payloads and extremely low ground pressure.

The Chieftain D can carry a payload of 13.6 tonnes whilst exerting a ground pressure of 3.7 psi. The deck is large enough to carry a 20ft (6.1 m) ISO container or flat rack.

With a payload of up to 36 tonnes and a load bed large enough for a 40ft (12.19 m) ISO container, the Husky 8 is the largest in the range, but even at this extreme weight, it exerts a ground pressure of only 4.6 psi.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

Summary

The British Army has many competing demands, and just because one person might think it is a good idea does not make it so. However, in the introduction and further reading references, it is clear that the area will be increasingly exploited for travel and commerce as climate change takes its toll. This inevitably means competition, pressure, and conflict will follow.

Mobility, and being able to access this terrain, should be a central component of any approach, even if it is a modest tilt.

We could modify existing, purchase the same equipment as our allies and the Royal Marines, or exploit the civilian market where many solutions also exist.

Interestingly, the defence market is dominated by centre-steer articulated vehicles, but whilst it offers many advantages, this is not as common in the exploration and mining industries. An articulated vehicle is freed from the overall vehicle from the ratio of width to length ratio limitation. For a given volume, one can therefore have a narrower/longer vehicle, but for heavier payloads and larger load beds, single chassis with multiple track units seems to be the norm.

As always, specialist equipment is needed for specialist requirements, can’t see a Boxer or Ajax doing very well in some of this terrain.

Further Reading

https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R41153.pdf

https://www.uscg.mil/Portals/0/Images/arctic/Arctic_Strategy_Book_APR_2019.pdf

https://www.army.mil/e2/downloads/rv7/about/2021_army_arctic_strategy.pdf

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Great article

another avenue possibly worth exploring is https://arctictrucks.com/vehicles-landing-page/

& exploring what modifications could be made to say vehicles such as unimog & man HX. As well as Hilux etc. It may also be that the wheel track replacement units could be applied to more standard vehicles?

Rheinmettal mission master XT may also be an interesting vehicle in this area.

Also another consideration could be hovercraft although limitations possibly provide fast transport over ice & snow?

Defence Select Committee has done good work, though this year’s output in strategy docs hardly had any mentions about implementation/ follow-through.

A quick look at a map (one was provided by TD) with the Ural mountains as the accepted border for Europe (georaphically) quickly shows how warped this defintion is, with its omission of Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlaya:

“‘European Arctic’, roughly stretching from Greenland in the West to the Norwegian/Russia border in the Barents Sea in the East, and encompassing areas of strategic importance such as the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) Gap and Svalbard.”

– noteworthy as it is not long ago when the Russian Forces had a major exercise about taking Svalbard, using these mentioned areas as ‘jumping off’ points

Great walk-thru – as usual – of what is available as existing solutions and the UK does not stand alone with its need to find a replacement for the BV206 utility versions.

… on the more fighty side of things, some catching up to do with the Ruskies who have modified there long serving, light pressure tracked APC into a light tank/IFV by adding a turret with a 30 mm autocannon. Already in service with their Arctic bdes

OK, the piece is from 2021, but since then Patria has come out with a rather interesting "FAMOUS"

… A must be for Arctic and M for Mobility; don´t ask me about the rest.

Well beyond a concept ( as shown in the normal defence industry gettogethers) by now and a good number of countries showing interest.

What are 'our interests'?