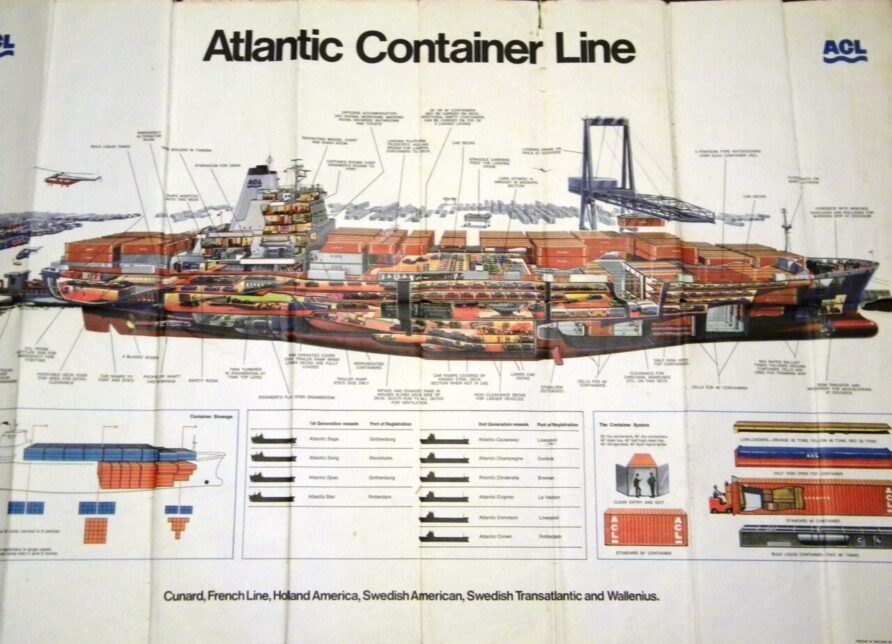

The Atlantic Conveyor was built on the Tyne by Swan Hunter and delivered to Cunard in 1970 as part of their contribution to the Atlantic Container Line consortium.

It would go on to be sunk by enemy action in the 1982 Falkland Islands conflict, where it served as an aircraft ferry.

This is her story.

Before the Falkland Islands Conflict

The Atlantic Container Line (ACL) consortium was founded in 1965, comprising Wallenius Lines (OW), Swedish America Line(SAL/Brostroms), The Transatlantic Steamship Company Limited (RABT) and Holland America Line (HAL).

The four were later joined by the Cunard Steamship Company and the French Compagnie Generale Transatlantique (CGT).

The Atlantic Conveyor was built on the Tyne by Swan Hunter and delivered to Cunard in 1970 as part of their contribution to the Atlantic Container Line consortium.

Vessels in the class included the Atlantic Crown (HAL), Atlantic Cinderella (HAL), Atlantic Cognac (CGT), Atlantic Champagne (CGT), Atlantic Causeway (Cunard), and the Atlantic Conveyor (Cunard).

These were revolutionary designs at the time, combining RORO and container storage in a single vessel, a CONRO.

Each of them displaced just under 15,000 tonnes and after construction, all started to traffic transatlantic routes and those to North Africa.

Falklands Requirements

By the beginning of April 1982, the invasion of the Falkland Islands by Argentina was imminent and in due course, after a brief firefight, Governor Rex Hunt ordered the Royal Marines garrison to surrender.

Don’t make yourself too comfy mate, we’ll be back.

Unknown British Royal Marine [as leaving, to Argentine guard]

Images of the prone Royal Marines were iconic but what was not widely known at the time was that the soldiers that ordered the Royal Marines to do so were admonished by an Argentine officer who then requested the Royal Marines stand up and be proud of themselves.

On the 3rd of April 1982, the UN passed Resolution 502, demanding the withdrawal of Argentine forces, a cessation of hostilities and a political solution.

This came as a surprise to the Argentine leadership, they genuinely thought the UN would support their intervention.

By then, the ‘British Military Machine’ was starting to move…

The Royal Navy (RN) and Royal Fleet Auxiliary (RFA) ships were not nearly enough for 3CDO, let alone the eventual force that sailed, help would be needed.

One must remember in 1982 UK forces were configured for ‘Cold War’ NATO tasks and expeditionary capabilities did not have the same priority as given to the expected Warsaw Pact thrust into Western Europe.

To support the logistics effort, several civilian vessels were therefore requisitioned under the ‘Ships Taken Up From Trade’ (STUFT) arrangements.

Other vessels were chartered and in total, just over 40 civilian vessels of many types took part in the conflict.

After some preparation, four Chinook helicopters from 18 Squadron RAF were detached to RNAS Culdrose to support the task force by ferrying all manner of supplies to the ships, including a 7-tonne drive shaft bearing.

The original plan was to deploy four aircraft to the Task Force and one at Ascension. It should not be forgotten that the Chinook had at that time, only been in service for a short time.

Harriers and Sea Harrier teams started preparations; the Harrier GR.3 was fitted with radar warning receivers and even modified to carry and fire the Sidewinder air-to-air missile.

Additional Harrier GR.3 modifications included tie-down points on the outriggers, changes to the nose wheel, various holes either drilled or plugged and changes to the navigation system, all to allow them to deploy from aircraft carriers.

After a meeting at the MoD on the 14th of April 1982 during which the concept was evolved, the SS Atlantic Conveyor was designated to carry several Harriers and helicopters south, the Harriers were to replace expected combat losses.

The Atlantic Conveyor was therefore NOT to be an aircraft carrier conversion, but primarily a transport vessel for Harriers and Chinooks,

She sailed from Liverpool the day after, bound for Devonport.

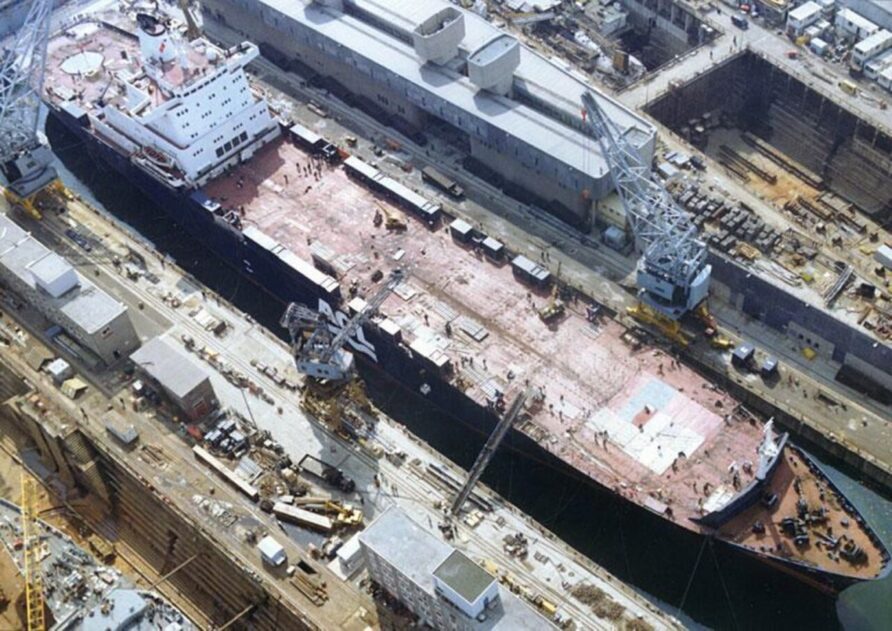

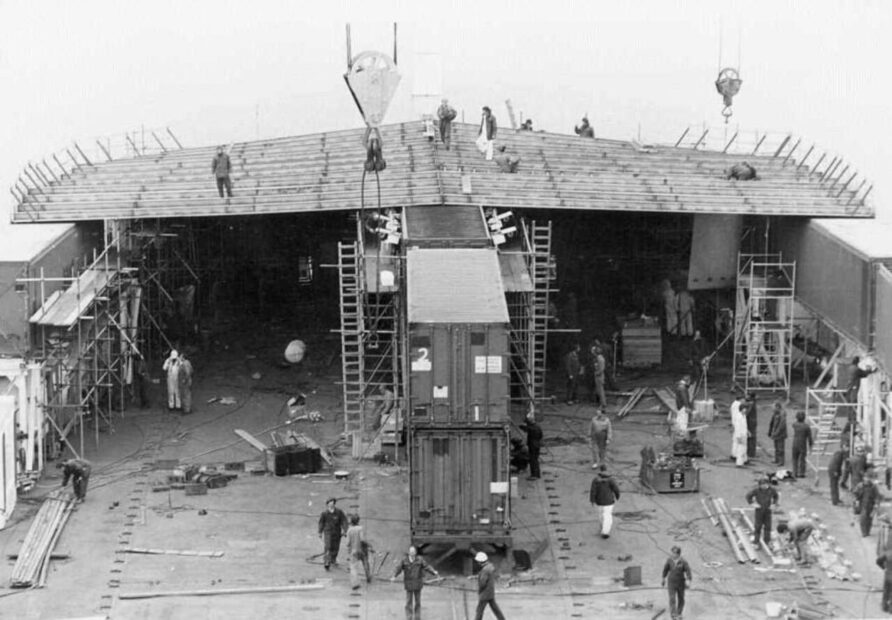

After arriving at Devonport on the 16th of April, her conversion started immediately.

Conversion and Departure

The modification package for the Atlantic Conveyor included covering the container hold with steel plates, fitting a Replenishment at Sea (RAS) system, creating a system of shelters and equipment stores on the deck using ISO containers/portacabins and installing additional communications equipment.

The containers on the deck were used for storing fresh water and oxygen, accommodation for 100 personnel of all three services, and workspaces for maintenance.

The stern container deck was also modified for helicopter operations.

The image below shows Captain Ian North (left) and Royal Navy Captain Mike Layard (right) on the bridge during conversion.

As described above, the original plan for the Atlantic Conveyor was to use her as an aircraft ferry only, but during some meetings on the 17th and 20th of April 1982, it was decided to make use of the valuable cargo spaces for other task force stores.

Because of these last-minute decisions, no additional magazine capacity was installed. Instead, 600 cluster bombs, rocket motors, anti-tank missiles, grenades and small arms ammunition were stored in normal containers.

This would have a significant bearing on the aftermath of the attack.

The vehicle decks were used for all manner of military stores including:

- Tentage and tent heaters for the entire task force

- 11 Squadron RE’s G10 stores,

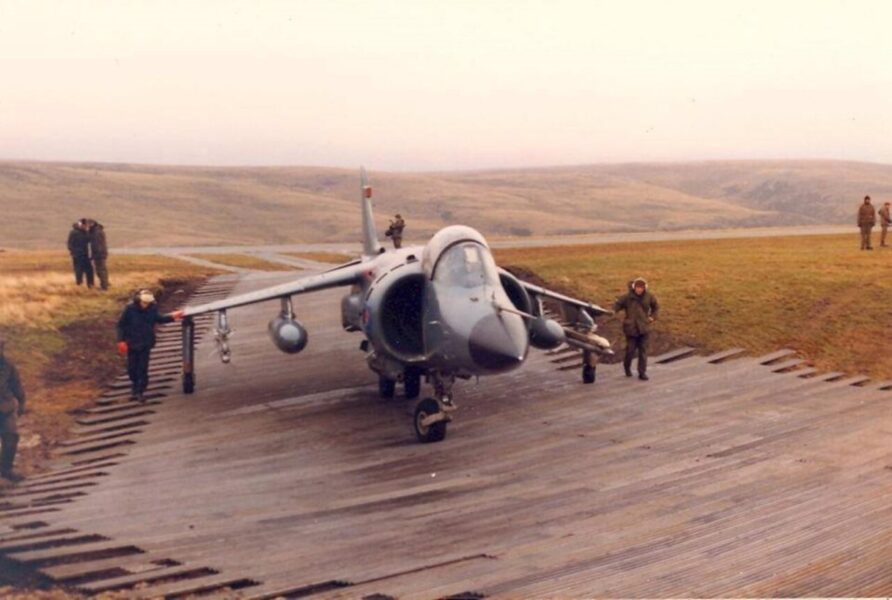

- Equipment and plant for the planned Harrier Forward Operating Base (FOB)

- Stacker trucks

- Twelve Combat Support Boats

- Specialist spares

- Dracones (floating rubber fuel tanks)

- Fuel pumping equipment

- Water desalination equipment

- Generators

- Lighting sets

- Non-aircraft munitions.

Helicopter and Sea Harrier (809 NAS) operations were also tested and confirmed, surely an incredible feat by Naval and civilian personnel, just to remind you of the time scale, 10 days.

Five Chinook HC.1’s of No. 18 Squadron RAF were flown to the Atlantic Conveyor, rotor blades removed and the airframes protected with Dri-Clad covers and corrosion inhibitors.

Joining the Chinooks were also six Wessex HU.5 of 848 NAS and a small number of Army Air Corps Scout helicopters.

RAS trials were conducted on the 24th of April 1982.

With Harrier GR.3 modifications and training still ongoing, the ship set sail for Ascension Island on the 25th of April 1982

Joining the Atlantic Conveyor for the voyage to Ascension Island were the MV Europic Ferry and MV Norland.

After departure, a number of the containers used for fuel storage leaked, and the aftermath of that would take a great deal of effort to resolve.

The Voyage South

On the 2nd of May, she arrived in Freetown, Sierra Leone, for refuelling and replenishment

Once complete she then sailed for Ascension Island.

The day after, the Harriers began their complex and demanding journey south.

Three days later, on the 5th, she arrived at the by then, buzzing, Ascension Island.

Stores were offloaded, loaded and re-stowed.

One of the Chinook’s was also embarked to be used for moving stores between ships.

The Sea Harriers and Harrier GR3s, after a series of record-breaking single-seat ferry flights from the UK arrived at Ascension

Then flown onto the Atlantic Conveyor.

A complex series of aircraft movements culminated in all aircraft being stowed for the onward journey to the Falkland Islands, eight Sea Harriers and six Harrier GR3s were to be carried south.

The ship left on the night of the 7th of May and the next day, the Harriers were covered with the same Dri-Clad bags that protected the helicopters.

The journey to the Maritime Exclusion Zone (MEZ) took until the 19th of May and during that time, one Sea Harrier was kept on ‘Deck Alert 20’ in the ‘anti-shadower’ role to protect against Argentine Air Force 707 reconnaissance flights.

With no tanker support, increasing temperatures and a fuel-intensive vertical take-off and landing, the mission would have been very challenging.

Wessex helicopters were used to transfer personnel and stores between the Atlantic Conveyor and the rest of the amphibious group sailing south.

Task Force Rendezvous

As the Atlantic Conveyor approached the Maritime Exclusion Zone the Harriers were de-bagged (stop laughing at the back) and further preparations were made for disembarkation.

HMS Hermes and HMS Invincible closed with the amphibious group on the 19th of May to allow the aircraft to transfer from the Atlantic Conveyor.

With a few engine problems and difficult conditions, this transfer took slightly longer than planned but by the 21st of May, all the Harriers were gone.

During this short period, the Atlantic Conveyor stayed in close proximity to the Battle Group, providing helicopter cargo support in which one Chinook and three Wessex were used extensively.

The first Chinook used was the famous Bravo November, flown off the front deck, after being debagged and bladed shortly before.

Next, to be prepared was Bravo Tango, but her departure was not to be (see images below)

Stores and munitions were also transferred and a Lynx disembarked.

With the Harriers no longer on board, the main mission of the Atlantic Conveyor had been achieved.

Exocet

On the night of the 21st of May 1982, the beachhead at San Carlos was established, with follow-on landings taking place soon after.

By the 24th, commanders felt increasing optimism; the beachhead had been secured, stores were being built up and combined forces had started to achieve the upper hand in the air war, despite significant losses.

Argentine commanders correctly assumed that the opportunity to dislodge British forces from San Carlos had passed and their best course of action was to disrupt the sustainment of the blockade.

The Atlantic Conveyor was instructed to be ready to move to San Carlos Water on the 25th of May under cover of darkness to disembark all helicopters and begin transferring all stores using Mexeflote’s and landing craft at first light.

Preparations on-board continued, including moving stores to disembarkation points and ‘ground testing’ of some of the remaining helicopters.

Captain North reportedly said to his crew;

Well boys, its May 25th, something spectacular should happen today

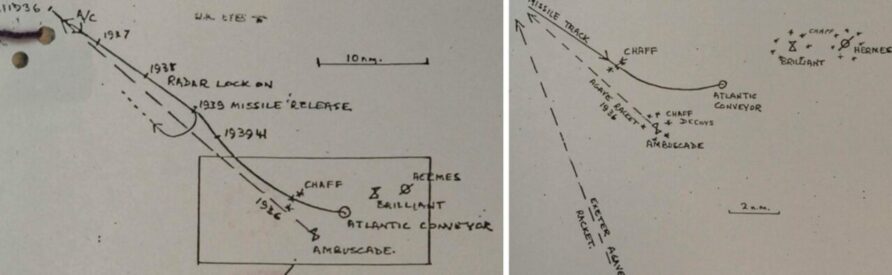

Meanwhile, two Super Etendards of CANA 2 Esc approached from the north after refuelling from a Hercules tanker.

A Chinook helicopter, Bravo November, after static engine tests, departed the ship from the forward deck for further testing and to transfer some stores, and Bravo Tango moved to the rear deck in readiness for flight testing.

During the final preparations of Bravao Tango, the call ‘Handbrake’ was received on board the RN ships, indicating a detected Super Etendard radar emission.

At 19.40, ‘Emergency Stations’ was sounded by the Atlantic Conveyor’s ship alarm.

A number of warships including HMS Alacrity deployed chaff countermeasures but whilst lured into the chaff cloud, the missiles flew through it and detected the Atlantic Conveyor.

She was hit by both missiles at C Deck.

The image showing the missile tracks below is taken from a now-declassified SECRET memo to the cabinet on the 2nd of June 1982.

There is some difference of opinion in public documents whether one or two missiles hit the Atlantic Conveyor.

The official Board of Inquiry stated two and three diary extracts from the HMS Brilliant website would also seem to confirm that.

Our weapon systems locked onto both the missiles and tracked them all the way in but they were unable to engage them because they were out of range. She was on fire within minutes of being hit and it was getting dark we were told to get in as close as we could and pick up people in life rafts.

We picked up a life raft with about 24 in while we were doing this about five floated past, they looked dead a couple had put their survival suits on wrong and were floating feet up. I think they were picked up by helicopter. It was a terrible feeling knowing it could have been you and so it goes on

and

The Captain put the ship into defence watches at 7.30 but I stayed in the Ops Room and we had an EW detection of Etendard radar at about 7.40, then shortly after this an unknown contact to the NW.

We then saw them – contacts double (obviously missile release) as the missiles started in. The system immediately acquired them and the T.V. monitors showed them heading some 5 miles NW of us toward the Atlantic Conveyor.

The missiles were so close together they were both on the same T.V. monitor. They were v. low and v. fast. We saw them hit the middle of the “Conveyor” and the explosion seemed to go through her and out the other side.

Finally,

While the rescue attempt were being carried out on Coventry two low aircraft were spotted at about 26 miles away from the force. They released Exocet missiles at 23 miles All the ships fired Chaff which is just bits of silver paper it worked for a second but the missiles locked on again straight into the stern of the Atlantic Conveyor.

The Board of Inquiry stated the following;

ACO hit by two Exocet, port quarter level with after end of superstructure, 10-12 feet above waterline. Missiles entered C cargo deck in vicinity of lift shaft. Ship in a port turn passing through approximately 90 degrees at the time

Multiple sources are clear that it was two missiles.

HMS Alacrity came alongside to attempt boundary cooling and RFA

Sir Percival also stood off the port quarter to render assistance.

Shrapnel was reported to be seen coming through the ship’s sides as ammunition and gas cylinders were exploding, despite this, helicopters rescued twenty-two personnel from the forward deck.

Damage control and firefighting continued, and ammunition was dumped overboard, but it was a losing battle, with systems failing and light fading fast, the decision was made to abandon ship at 20.05, 25 minutes after the attack.

The fires were assessed as being uncontrollable with a high risk of spreading to the forward hold where considerable quantities of kerosene and cluster bombs were stored.

Unable to land on the ship, Bravo November landed on the aircraft carrier, HMS Hermes.

The ship’s captain threatened to have the Chinook pushed overboard if it was not removed because it would hamper the carrier’s ability to mount its own air operations. After an overnight stay the aircraft departed for the bridgehead at San Carlos.

Despite the valiant efforts of those involved, twelve men lost their lives. Three were lost on board and nine after entering the water.

In total, one hundred and thirty-seven out of the one hundred and forty-nine on board were rescued, obviously a great credit to all involved and a testament to the calm and orderly manner in which the ship was abandoned.

The last lifeboat was recovered by HMS Alacrity at 23.00.

The 12 men killed in the sinking of the Atlantic Conveyor were:

Merchant Navy

- Bosun (Petty Officer I) John B. Dobson

- Mechanic (Petty Officer I) Frank Foulkes

- Assistant Steward David R. S. Hawkins

- Mechanic (Petty Officer II) James Hughes

- Captain Ian H. North, DSC

- Mechanic (Petty Officer II) Ernest M. Vickers

Royal Fleet Auxiliary

- First Radio Officer Ronald Hoole

- Laundryman Ng Por

- Laundryman Chan Chi Shing

Royal Navy

- Chief Petty Officer Edmund Flanagan

- Air Engineering Mechanic (R) Adrian J. Anslow

- Leading Air Engineering Mechanic (L) Don L. Pryce

I thought this, from the London Gazette for Captain North was fitting.

Captain Ian Harry NORTH, Merchant Navy. On 14th April 1982 SS ATLANTIC CONVEYOR was laid up in Liverpool. On the 25th April she deployed to the South Atlantic converted to operate fixed and rotary wing aircraft and loaded with stores and equipment for the Falkland’s Task Force. This astonishing feat was largely due to Captain North’s innovation, leadership and inexhaustible energy.

SS ATLANTIC CONVEYOR joined the Carrier Battle Group on 19th May 1982 and was immediately treated as a warship in most respects. Almost comparable in manoeuvrability, flexibility and response Captain North and the ship came through with flying colours. When the ship was hit on 25th May Captain North was a tower of strength during the difficult period of damage assessment leading up to the decision to abandon ship. He left the ship last with enormous dignity and calm and his subsequent death was a blow to all.

A brilliant seaman, brave in war, immensely revered and loved his contribution to the Campaign was enormous and epitomised the great spirit of the Merchant Service

And another.

Third Engineer Brian Robert WILLIAMS, Merchant Navy.

At the time when ATLANTIC CONVEYOR was hit by Exocet missiles. Mr Williams, the Engineer Officer was stationed on watch

in the Engine Control Room with the mechanic. Soon after the missiles hit, the mechanic left the room and shortly after this was heard calling for help. The room was filling with smoke and would shortly be abandoned. Nonetheless Mr Williams promptly put on breathing apparatus and set off to the rescue of the mechanic whom he found, following a further large explosion, seriously injured and trapped in a way that assistance would be required to release him.Mr Williams went quickly to get help.

Then, realising that a further rescue mission was a forlorn hope and knowing that there was a grave risk of further explosions and the spread of fire, he armed himself with asbestos gloves and fresh breathing apparatus and accompanied by the Doctor and a PO Engineer again braved the appalling heat and smoke for a further attempt to rescue the mechanic. However, as they approached, the conditions became literally unbearable and the mission had to be abandoned. Mr Williams made his report calmly and then went to the Breathing Apparatus store where he began valiant efforts to recharge air breathing bottles. He was eventually ordered to the upper deck to abandon ship.

Throughout the incident Mr Williams showed exceptional bravery and leadership and a total disregard for his own safety

Brave men all.

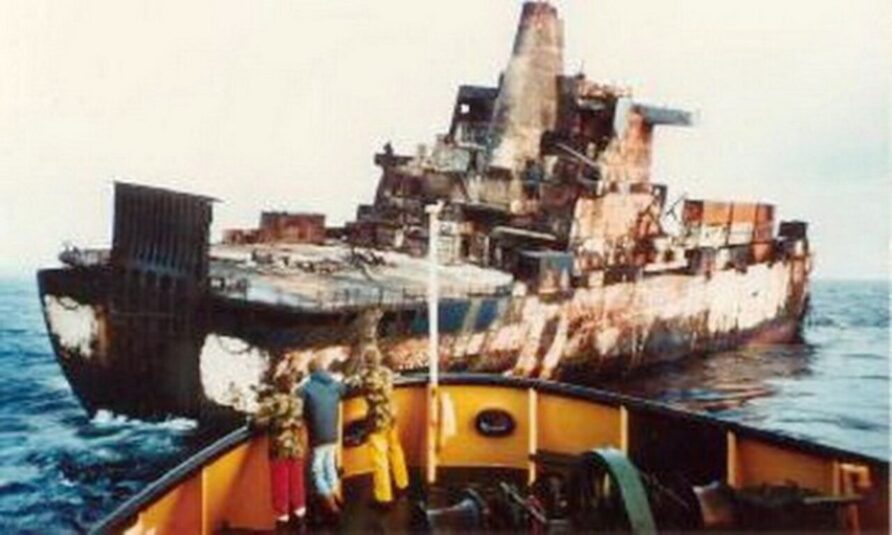

A Wessex helicopter from HMS Hermes photographed the still-burning ship the day after the attack.

On the 27th at 50305 5451W, the Atlantic Conveyor was again sighted and although the bow section had been completely destroyed by exploding cluster bombs and fuel, a decision was made to attempt to bring her under tow using the tug, The Irishman, one of the STUFT vessels.

Despite repeated efforts of the crew of The Irishman, she sank in the early hours of the 28th of May, 1982.

Three containers were sighted floating at the position where it was assumed she sank.

A handful of comments from an older version of this text at the Think Defence blog.

The Conveyor was with us as we had been cross decking harriers and kit all day. I can remember the action station alarm going off and the urgency in the voice of the person sounding the alarm and we knew it was close. When I closed up to my action station I got kitted up I opened the weather deck access door for a peek to see what was happening. I could see her clearly ablaze especially around the superstructure lads running up and down the deck donning there once only survival suits and going over the side as she was that close to us. Then all the helicopters started closing in on her and winching up the lads out of the water and from the life rafts. I knew several of the lads who were on her and they were brought over to us. It seemed quite funny at the time in a strange way and we were taking the piss out of them (gallows humour I suppose) then I can remember looking at them and seeing the shock in their eyes and the reality of what had just happened to them sank in. Had she not taken the hit would it have taken us?

Hermes 82

I was embarked on the Conveyor (848 NAS) at this time. There has always been a debate as to whether we were hit by one or two missiles – it doesn’t really matter I guess, despite gallant efforts, there was nothing we could do to save her. The lone question I have always carried with me is, if she was so important to the success of the landings, why weren’t we better protected?

Peter Burris

I was spreading the rotors of the Wessex 5 just aft of the forward flight deck when we were hit. A scary time for a young 19-year-old, but recently my mind has been blown away by a fact that I read in the “Board of Enquiry” of the sinking of the AC. I was rescued by a Wessex 5 of 845 Squadron “YD” XT459. I didn’t know this until last week when I read the report. In December 1983, I was on operation “Clockwork” in northern Norway, left-hand seat in “YD” when we spiralled in nose first from 1200ft. I’m in shock that the same aircraft rescued me, then 19 months later nearly killed me!

Phil Russo

I was on the Alacrity at the time we had detected the Etendards and had fired chaff resulting in the conveyor being hit. we spent the next few hours first tied up alongside trying to firefight and rescue survivors but it was too rough and we were getting smashed together. We then stood off and put swimmers into rescue survivors and recover some of those less fortunate.

Stevey

Was serving aboard HMS Alacrity at the time. As I recall the Exocet(s) were aimed at us and the carriers, but we sent up loads of chaff which confused the missile(s), which carried on past us and then, as programmed, they hunted for the next large object which happened to be Atlantic Conveyor, about a mile away from us? Alacrity was first alongside, and as Stevey correctly stated, it was far too rough for us to stay alongside for long, especially as it turned out that the Alacrity’s hull was already in poor condition due to the battering it took down south. I recall vividly hauling some bodies on board, we had nowhere to store them, so we had to temporarily stow them in one of our ammunition stores. It was another terrible day, coming only four and two days after losing two of our sisters, Ardent and Antelope respectively. Morale was pretty low for a time. Dave “Bungy” Williams WEM(R)1

David J Williams

Certainly brought back a few memories for me! 54 merchant ships were taken up from trade (STUFT) to assist the armed forces during the South Atlantic conflict. 43 sailed for the South Atlantic with Merchant Navy crews and Naval Parties embarked, before the Argentine surrender on 15th June

Commander Nick Messinger RD** FNI RNR Retd

Aftermath

Although the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor ultimately did not change the result of the campaign and her primary mission of delivering the precious Harriers and Sea Harriers completed, her loss would be acutely felt.

In addition to the huge volume of stores, three Chinook, six Wessex and a Lynx helicopter were lost, including all their specialist tools, spares and manuals.

The original plan called for the Chinooks from Atlantic Conveyor to move an entire Commando to secure Mount Kent with another Commando and Parachute Battalion to Teal Inlet and Douglas Settlement.

The news of the Atlantic Conveyors’ loss came as a bitter blow.

We’ll have to bloody well walk then

The remaining Chinook, the famous Bravo November, would be kept flying with borrowed tools and improvised engineering but one thing was certain, the route to Stanley would be made largely on foot.

Although Sea King and Wessex helicopters could both lift external sling loads, they were in no way comparable to that of the Chinook.

With only one Chinook available, priorities would mean that it would be largely used for supporting the Royal Artillery Light Guns.

No large-scale moves of infantry forces by helicopter were possible and most of the troops had to walk (tabbing or yomping, depending on the colour of your beret) up to fifty miles across East Falkland, from San Carlos to Stanley, before starting the main attack, a feat of arms that is still notable today.

The impact of a shortage of helicopter lift on the decision to attack Goose Green and the subsequent tactics is interesting to debate but the most significant impact would be the decision to send 5 Infantry Brigade to land at Bluff Cove with its subsequent losses.

Another significant implication of the sinking was on plans for the Harrier Forward Operating Base (FOB) at San Carlos.

It was a huge blow to the construction of the FOB, compounded by the fact that many of the Sappers’ vehicles were unable to be offloaded from RFA Sir Lancelot because of unexploded bombs.

On the SS Atlantic Conveyor were all of 11 Squadron’s stores, i.e. the FOB and the means to create it (engineering plant etc.).

All was not lost, though, supplementing the initial stores being used to build the FOB, on RFA Stromness was a small quantity of PSA (Prefabricated Surfacing Airfield) panels that were used for bomb damage repair and vertical take-off and landing pads.

The loss of fuel dracones and associated pumping and storage equipment meant fuel was always a problem, arguably, the task force would not have been able to sustain the three Chinook helicopters lost in any case without it.

On 11th June the British force mounted a brigade-sized night attack on Argentine positions in the mountains surrounding Stanley and three days later, after heavy fighting in the area, the Argentine garrison surrendered.

Because the Task Force tentage, heaters and most of the generators and lighting sets were lost with the Atlantic Conveyor, post-ceasefire arrangements would be extremely challenging until additional stocks could be transported south.

Controversy

There remains to this day some controversy about the level of protection afforded the Atlantic Conveyor, why one of the two Seawolf armed Type 22 frigates was not assigned to escort her, why no self-protection measures were installed and whether, given the significance of the 25th of May, she was in a danger area in the first place.

After the BOI report was released in 2007 the newspapers printed the headline-grabbing news that Atlantic Conveyor was left defenceless over concerns about legality.

From the Times, December 11th 2007

A helicopter-carrying merchant ship that sank with the loss of 12 men after being hit by two Exocet missiles in the 1982 Falklands conflict was unarmed and unprotected because Ministry of Defence lawyers feared that it was illegal to fit a commercial vessel with weapon systems, according to newly released classified documents

The full BOI report can be found here, which includes an extensive narrative and a great deal of supplementary information including information on how the explosives, ammunition, bombs and other hazardous stores were stowed.

The key parts are in Attachments 1 and 2, these cover the subject of self-protection measures, stowage and damage control issues.

The vessel might have been stationed further east until the Chinooks were ready to fly off, and some of the FOB stores and engineering plant distributed on other vessels, perhaps she could have possibly stayed in a safer area until the Seawolf-armed HMS Andromeda arrived on the 26th.

It is easy to see things with perfect 20:20 hindsight and be wise after the event but I think any discussion must take into account the incredibly short time in which conversion and operations took place and the comparative risks to the operational success of protecting the Atlantic Conveyor and protecting the carriers.

Tough times needed tough decisions.

Sister

The Atlantic Conveyor had a less well-known sister ship that also took part in operations in the South Atlantic.

The Atlantic Causeway was pressed into service in the same time frame but with a different set of modifications.

Requisitioned on the 4th of May and taken to Devonport on the 6th, she was converted to carry, operate and support helicopters.

The conversion differed from the Atlantic Conveyor in having a large hangar forward and improved aviation fuel handling facilities that supported operating helicopters, not just transporting them.

Atlantic Causeway sailed on the 14th of May with 28 helicopters and arrived in the Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) on the 27th of the same month, disembarking her aircraft and stores in San Carlos Water from the 31st of May.

From Hansard;

HC Deb 22 December 1983 vol 51 c424W 424W

Mr. Dalyell asked the Secretary of State for Defence what has been the cost of converting the Atlantic Causeway into a ship capable of carrying helicopters.

Mr. Lee The Atlantic Causeway was taken up from trade and converted to transport aircraft and stores during the Falklands emergency. She has since been restored and returned to her owners. The total cost of conversion and restoration was about £2 million.

During the operation, she received 4000 helicopter landings and refuelled aircraft 500 times, an impressive feat for conversion and restoration that cost £2 million.

Another couple of merchant conversions are also worth mentioning, although not of the same design, MV Astronomer.

After unloading all cargo and containers, she was sailed to Devonport and converted to the helicopter forward support ship, sailing South on the 8th of June 1982.

The six-day conversion included the installation of a landing pad, hangar, RAS gear, communications equipment, additional accommodation and self-defence equipment.

In addition to three Chinook, Wessex and Sea King helicopters, the ship had its crew of 34 joined by 53 Royal Navy, 21 RAF and 8 Army personnel.

During her time in the Falkland Islands, the MV Astronomer carried out all manner of aviation support, patrol and logistics activities.

The one-thousandth landing was completed by a Royal Navy Sea King from HMS Invincible by the end of August.

And MV Contender Bezant, or RFA Argus as she would later become.

MV Contender Bezant was utilised as an aircraft transport, ferrying helicopters and Harriers south to the Falkland Islands.

Following purchase by the MoD in 1985 for £13million she was converted to an aviation training ship at the shipyard of Harland & Wolff, Belfast, with the addition of extended accommodation, a flight deck, aircraft lifts and naval radar and communications suites. A Primary Casualty Receiving Facility was added before Argus was sent to participate in the 1991 Gulf War.

Another role of RFA Argus is that of RORO vehicle transport with vehicles carried in the hangar and on the flight deck, a role she performed in support of United Nations operations in the former Yugoslavia.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Argus was again present in the Persian Gulf as an offshore hospital for coalition troops, earning the nickname “BUPA Baghdad”.

Most famously, RFA Argus participated in OP GRITROCK, the UK’s response to the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone, and of course, a star turn in the Brad Pitt film, World War Z.

ZA718 Bravo November

No story of the Atlantic Conveyor would be complete without some reference to the one that got away, Bravo November

During the attack on the Atlantic Conveyor, Bravo November was moving a netted cargo of Lynx spares and was therefore still in the air, after being ordered to hold the position for a short period the helicopter returned to HMS Hermes.

The large Chinook on the crowded deck of HMS Hermes caused some problems for aircraft movement and consideration was given to sawing the blades off and stowing it below or even dumping it over the side in best Vietnam fashion.

Thankfully, these options were eventually discounted and the next morning it was refuelled and flown to the Falkland Islands.

In one mission, it carried 28 men and two 105mm Light Gun in the cabin, plus another Light Gun slung, must have been a tight squeeze!

Another mission included carrying 81 fully tooled-up Paras to Fitzroy, yes, 81.

From commencing operations until the Argentine surrender, Bravo November moved 1,530 troops, 650 POW’s and 1,600 tonnes of stores.

It is difficult to see how the Royal Artillery could have kept up the intense Light Gun firing rate without the heavy lift provided by Bravo November.

Memorial

In June 2007 a memorial to those lost on the Atlantic Conveyor was unveiled at Cape Pembroke, the most Easterly point on the Falkland Islands, near the now disused lighthouse.

Up until that point, she was the only vessel sunk in the conflict without a memorial.

The memorial features a propeller and shaft that has been aligned on a magnetic bearing of 62 degrees to indicate the point, 90 miles out, where the MV Atlantic Conveyor finally came to rest.

In 2008 the Protection of Military Remains Act (PMRA) 1986 was extended to include the Atlantic Conveyor

A Lighter Note

Thought I would end this on a lighter note, an urban myth perhaps, but a good one.

Because it was not absolutely clear what stores were on board, it was said for years after the sinking, every enterprising Quartermaster (QM) in the British Army seized the opportunity and indented for equipment that supposedly ‘went down on the Atlantic Conveyor’

The amount of kit thus claimed would have been enough to fill several Atlantic Conveyors.

The best one I heard was that some old tentage, still on the books from the Boer War, was finally written off as being lost on the Atlantic Conveyor!

Change Date Change Record 01/03/2017 initial issue 12/01/2021 Format update and inclusion of additional information received in comments 14/07/2021 Refresh and update 24/08/2023Refresh and update

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

http://www.josepinera.com/josepinera/Jp_ABC_memo_Matthei.htm

The reason why Thatcher tried to get Pinochet released. And why AEW is so important for naval task forces

Growing up where I did, I met a few FAA pilots. One was on the Atlantic Conveyor. He never discussed it with me, but my parents said his wife reported that the RN was no longer the “fun” job afterwards: he stayed in, but it was more duty than anything else.

Great post TD, great post.

My Yeoman instructor at HMS Mercury was a AC “survivor”. My very good friend was first mate of the Irishman and got the OBE (or BEM ?) for the salvage efforts.

In 87 when I deployed to the gulf on an a Hunt Class MCMV we got a ‘radar warning receiver’ and “Barricade” chaff and flare launchers – cheap, simple, easy to operate systems – perhaps if they were around five years earlier AC might have dodged the bullet ? Of course fitting her with guns would have made no difference – although a RAF Reqiment friend once noted that early in 82 the US Army in Germany had just retired a whole battalion of towed 20mm Vulcan air-defence systems – the same gattling gun as used in Phalanx, but with optical sights and a small tracking radar – take the wheels off and weld it to the deck ? Hindsight eh ……

Really when you consider the kit she was carry, she was about as much as a High Value Unit (HVU) as the carriers, could we not have found a Seawolf equipped Leander or T22 to act as “Goalkeeper” (very close escort).

Amazing what can be acheived in a short time when the pressure is really on. What was done then could plausibly be done again.

OTOH a purpose built ‘Aviation RFA’, or even a very austere planned conversion, would have: damage control, magazines and mounting for CIWS.

Great post. Thanks.

“The amount of kit thus claimed would have been enough to fill several Atlantic Conveyors.” – CPO Pertwee would have been proud…

Really good article boss.

Re; Sea Cat

One confirmed kill of a Skyhawk by Type 12 HMS Yarmouth, who had a surprisingly active campaign. Also a Sea Cat was listed as a possible in a kill of another Skyhawk, though a Rapier and Blowpipe both have claims to that kill.

Sea Wolf – 4 kills,

Sea Dart – 7 kills,

Rapier – 1 confirmed,

Blowpipe – 1 confirmed,

Stinger – 2,

AA fire – 4,

“Not enough credit is given here to soft kill capabilities, i.e. decoys and jamming.”

And this is why we must all here recognise that our opinions and comments and above all, criticisms must be tempered with the realisation that we don’t and cannot know everything.

For example, one might criticise the RN for not having enough CIWS yet soft kill may be far more effective as is said and our ships as safe as they can be with it. But because we cannot know about its abilities we cannot comment on it. Which skews the whole debate.

x,

The Falklands was a long time ago, and supposedly ‘modern’ systems failed on both sides (Argentine bombs and ASW tactics?). There were a lot of lessons learned from the mistakes that were made, and I’d like to think that analysis process is better today than ever. Besides, we took a blue water navy optimised for North Atlantic submarine hunting and effected an amphibious invasion of defended territory against a capable aggressor, so no surprise things went wrong. Atlantic Conveyor could have survived the Exocet raid if the escorts had placed their chaff better.

Warship design, like everything else, is always a compromise of affordability against probable threat. The RN has elected to follow a certain philosophy in its warship design which compared to some navies may seem inadequate, and to others overkill. We’re in the midst of an update process (SWMLU, 997, Aster/Sampson, SeaCeptor) that will allow us to deal with the newest generation of threats as well as the old, and the soft kill systems are not being ignored. Harpoon may be old and slow, but it is still quite difficult to defeat by all but the most modern navies. None of it is perfect, but it could be a lot worse.

Funny how a USN commander would make such a comment. After all it was a 42 that shot down the Silkworm that was heading for the Missouri in GW1 whilst its escort was busy shooting at chaff (although to be fair it would probably have just bounced off the Missouri).

James, I do believe you have discovered the first thing that we can all agree on.

Have all AR govt ministers indicted for war reparations, minefield clearing etc, and make them subject to Euro arrest warrants when they leave office :-)

Don’t see why lawfare should apply one the one way….

Just added a handful of additional images

I’ve seen pictures of the Atlantic Conveyor after the bows were blown/broken off. Could you please put some images of that on your page?

Yours sincerely

Alan Erskine

Very interesting site, thanks a lot for making it. Just wondering at what depth the wreck of AC lays at?

Hope You understand my grammar, I´m swede, not fluent in english. Neither there isn´t so much info in swedish about the Falkland Conflict and the vessels being used.

Regards, Björn.

Alan, I don’t think the bow was actually broken off, the ship died by burning, not massive structural failure.

http://www.fourfax.co.uk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/1982_05_25-Atlantic-Conveyor-Sinking.jpg

As you can see here, the bow’s still intact. It sank while they were trying to tow it back to shore.

I don’t fully understand the legalities put forward re defensive armament of ‘auxiliaries’. Even as long ago as the Beira blockade some RFA’s carried small arms and a few had Bofors that were carried below decks (usually under the for’d deck housing) wrapped in protective greased cloth.. Occasionally mounted and tested before being re-stowed. I think that it was all a rather grey area that was brought to light during Corporate. The eventual defensive armament fit for RFA’s was through a major effort by an RFA Captain, Gordon Butterworth, who was attached to the MoD, who brought some reality to the Civil Servants of the day. In any case the whole shebang was, a few years later, put under the direct auspice’s of CinC fleet – something that I personally thought should have been done many years previously.

An insight to the Falklands War that a lot of people will never know about. I couldn’t stop reading this account.

During WW2 CAM ships (Catapult Aircraft Merchantmen) launched an old Hurricane on a one way trip to shoot down German Condors that stalked the convoys.

Am I right in thinking that during the “Battle of the River Plate” film there is mention of a British merchant ship that was armed with a single 4″ gun?

Jumping to the present day, do not nuclear fuel/cargo ships have a 30 or 35mm turret?

In my mind is an image of one of the STUFTs mounting a pair of Bofors guns, but perhaps memory is playing tricks.

“There remains to this day a question of why the Atlantic Conveyor was not provided with a suitable Sea Wolf armed escort “.

Nonsense. There were two GWS25-armed ships in theatre at the time. Each one assigned to goalkeeping an MEU (vice an HVU like ACO). No question whatsoever. Andromeda didn’t arrive until shortly after. Frankly a little naughty dropping that line under a sub-heading “controversy” – even with the caveat re hindsight.

“In my mind is an image of one of the STUFTs mounting a pair of Bofors guns, but perhaps memory is playing tricks”. That would be MV Elk whose master and SNO seemed to be particularly adept at proffing things that might be useful.

I think it is a fair sentence, it is the existence of a question, not whether it is a justified statement. You still see people discussing it i.e it exists

Much like the like the chaff and warning receivers in a legal context is a question

Both, clearly, can be explained.

There is also the fact that she received an instruction to turn, which put her side on. With no instruction, she would have remained stern on and some speculate the ramp might have afforded her some protection.

Andromeda arrived the day after, many also question why the ACO could not have been held east for another day. There is also the point that on the 25th, Broadsword was paired with Coventry and might have been positioned for covering ACO.

All exist as questions, although perhaps a better word choice would have been controversy, or at least context explained

I tend to the view that there was a slight under appreciation of the value of Chinook in the RN and the same for the potential of the FOB, but both are entirely understandable because Chinook was only very recently in service, the RM did not use them and there was no cooperation between RAF and FAA on FOB capabilities beforehand, or any kind of experience on which to make reference to

A very good friend of mine was 1st Mate on the Irishman and was awarded the MBE for his efforts in getting those tow’s secured in horrible weather. My instructor Yeoman at HMS Mercury in 83 was at times a bit odd. After passing out I was told he was the CY of the naval party onboard the ACO, and that he had been picked out of the water as dead, put in a body bag and thrown in the back of a Sea King, where he warmed up and came to, giving the flight crew the fright of their life. No wonder he was a bit odd at times…….

To be very fair, the escorts did their jobs, they fired chaff and decoyed the missiles away from the Ambuscade, which was probably their primary target. It was only extreme mischance that causes them to lock on to another target. If you looked at the memo that was so kindly provided, you would see that the original missile track was almost 45 degrees away from the original path.

It’s almost like a bullet ricochet, you never know where the round is going to go, and in this case, sheer bad luck is to blame for putting the Atlantic Conveyor right in the path of the rogue missiles.

Which goes to show Murphy’s Law is still king of the battlefield.

Have tweaked the content to add context to the Seawolf thing

In the current context there is nothing legally wrong with arming merchant vessels taken up from trade. STUFT assume the legal status of auxiliaries, that is ‘a government owned or operated vessel on non-commercial service’. There is no restriction on providing them with a self-defence capability as we are expecting vessels to operate in a hostile environment. Individual members of the crew may not be armed, as they are not combatants (though they are civilians directly participating in hostilities), but the vessels can be equipped with weapons for self defence.

It might simply have been the case that there were either insufficient chaff launchers available in a short timeframe to provide a self-defence capability, or it could have been decided that since there was not way of reliably cueing the chaff launchers to a threat (i.e. no ESM systems, no radars, takes too long to warn by radio, etc), there was little point in fitting them. A Bofors is not going to be much use against an Exocet.

BRd3012 Handbook on the Law of Maritime Operations refers – if you can get it.

In the days of SeaCat and SeaWolfs, it would have been very difficult to defend the Merchant vessels from ASMs. A 40 mm gun will be no help, and 20mm CIWS (= the only possible measure for ASM defense), was not popular and not easy to purchase around 1982.

I suppose, that is the reason ASTER and CAMMs are developed. With CAMMs, 1 or 2 frigate will be able to air-cover the RFA and merchant vessel fleets. This is game changing, I guess, and now there is no need to arm your Merchant fleet.

@TD. Facinating and seriously heroic. Thank you.

@DoT. Right on SeaCat (world’s first unguided missile), wrong on Sea Wolf – which is why T22s Broadsword, Brilliant and later Andromeda were in such high demand – system was newly in service and insufficient ships with the beggars to go around.

@Donald_of_Tokyo

I think that you will find most of the RFA flotilla are now defensively armed with Phalanx/Lmg’s/Mini guns et al. Agree with TAS regarding general legalities. However regarding the standing of RFA civilian crews; I have been researching same and certainly, according to WIKI their position seems quite convoluted and hybrid – Civil Service sailors with special RNR standing when in harms way, legally under Naval discipline. I was aware for some time that certain RFA officers and cpo’s were given naval gunnery instructions for the operation of weapons smaller than Phalanx. As I say, it is all rather convoluted but obviously legal if RNR regulations apply when the vessel is in a combat situation. I’m sure others will have a view. It definitely seems a ‘one off’.

The old Horizon documentary sets out the thinking why merchantman should not be armed:

https://youtu.be/yDYx84DdJ-w?t=306

This brings back many memories , I served on the Hermes down South . I came up from below when action stations sounded , my station was on the Flight Deck , as the chief in charge of aircraft salvage if required. I went to the back of the island and my first instinct when I seen a ship with a mass of smoke coming from , I thought she’s making a lot of smoke to keep up with us. It was then I realised the ship had been hit. When the first helicopter arrived with survivors , it flew down the port side and I seen it was full of men in there orange survival suits, on the deck everyone was brilliant making space so it could land. When the aircraft landed and the survivors disembarked , I recognised a few of them from MARTSU ( Mobil aircraft repair and transport salvage unit ) I gave them my bar number and took them to the mess , then I returned to the deck to assist. What sticks in my mind was the announcement from Flyco ” can we make room on the deck for one Chinock helicopter it doesn’t have a home !!!”

One of our PO’s had been over to the AC to check out on liquid oxygen earlier in the month , when he was getting ready to fly back to the Hermes , the guys on the AC questioned the way he was putting his survival suit on. RIP the ones who never returned.

Welcome to TD George, and thanks for your comment

Glad to the Atlantic Conveyor hasn’t been forgotten. While I respect the British mobilization of merchant ships.

And the speed that it was accomplished. But I never understood why they were so unprotected in a

combat zone.

Even here in the States we haven’t forgotten the Sheffield, the Ardent, the Antelope the Coventry or the

Conveyor. Not even the tough little Sir Galahad.

It’s good to see they haven’t been forgotten in the Falklands either.

Rue Britannia!

Good read that. A slight tangent. Your text makes mention of the initial invasion on 2 April with 1 dead and 2 injured Argentine soldiers. There’s a book knocking around, published within the last year, purporting to tell the “real” story of the defence i.e. the Royals put up a proper fight over many hours and inflicted many more casualties on the Argentine forces. There are strange claims to sightings of a British submarine and a hitherto unknown group of SBS troops that blew up a Arg landing craft killing 30+ men. There are outlandish claims that, to cover up the scale of losses, the Argies took bodies to a small island just outside Stanley and napalmed them! Some of this is likely to be hyperbole but I would like to think our web-footed friends did in fact give Johnny Dago a proper bloody nose on 2 April

It was good to see that the loss of the Atlantic conveyor has not been forgotten as I was a crew member onboard her and was transferred to another ship prior to her being requisitioned for the Falklands war, the modifications built into the new Atlantic conveyor (Class GR3) at the request of the MOD were always maintenance to the highest standard in readiness for their use if required, In 1991 the new replacement Atlantic Conveyor was called into Service like her predecessor to provide logistical support for the British forces taking part in operation granby (The First Gulf War) and the vessel provided the ability to deliver the largest single shipment of Military ordinance to the operating theatre for the Uk forces.

I served on the vessel at this time and must give credit to some of my fellow shipmates onboard who were serving onboard the previous vessel when she was lost in the falklands war and in the true spirit of the British Merchant seamen when called upon to serve their country stepped forward and took up the challenge as had every merchant seaman before them had done over the years.

My Name is Rosemary Anslow I am the Mother of Adrian Anslow who was lost on the Atlantic Conveyor.

Nothing can bring our Son back he was Lost to us doing his duty.

Adrian didn’t hesitate when he was called to do his duty .He loved the R N .

After 38yrs without him I still cannot help but think had the people that sent him to war should have protected him on his mission. Had he have been on the ground he would have been armed with some kind of weapon.

As it happens he was on a ship with no protection at all!! He was 20 yrs old!!!!

He was no more and no less than the next man but he was our son and I think we have every right to question how on earth could this happen. ,!! Needless to say as a family we still morn the Great loss of Adrian.

One day in the depth of my despair I asked God to help me to carry on.

I have always been able to put pen to paper and write .

I reached for a pen and wrote these words.

The Evening Light had faded

The night was still and cold

The Mighty ship stood Waiting unprotected from the Evil of man

She roared but Gentle as a Lamb she took you to her side

Held you close to her soul,

She Whispered come to me

I am your Mother The Sea

And Then The Shepherd Him most High

Took you to your rest

A Light shone around and a Voice called them Home.

At the time I was not sure about the protection on the Conveyor

It must never Happen again

God Bless all who were Lost to us

R I P

I was a junior purser on RAG Regent. As I was crossing the deck from ship’s office to tack bay, remember seeing missiles. Heading for Conveyor. No mention of the Regent and what had been transferred on to her!!! We were just off her starboard side. If you have the facilities to check, we were informed to change position with her!

The bravery and calm heard over the radio was amazing.

This is a long shot. My friend Derek Bernard Andrews recently passed away. Whilst helping his wife with paperwork I discovered that he mentioned being in the Falklands campaign. His wife recounted that he was on a cargo ship that had been hit by missiles. Ironically French missiles and his wife is French. I believe that he was a RNR volunteer and into radio communications. There remains a small piece of cloth with RNR 35474. He wrote that in May 1983 he was awarded The Queens medal for gallantry. The citation Falklands War duties, saved men & equipment. The presentation by HRHPrince Philip Admiral of the Fleet. He recounted to his wife that he had been injured in some way and that during treatment on another ship (which could have been Hermes) he had a bad allergic reaction. I have tried to find out more information to bring the pieces of the puzzle together. I can find absolutely no trace of him. He never even mentioned anything to his immediate family. Is anyone out there who can help?

What an Excellent Piece you wrote and research involved.

When She Sank I heard at the time that Certain Millitary were snooping around the Wreck for Hi Tech classified cargo/equipment…and Royal Navy Divers had been Down to Recover, or Destroy what was left on Board and keeping an eye on the area.

That was Back in 82 I heard that.

Thank You for your excellent piece which I have only just come across. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it and I believe it makes a solid record of events. As an Atlantic Conveyor survivor myself (18Sqn), I thought you might wantt to consider just a few points:

Conversion and Departure – “The containers on deck were used for storing fresh water and oxygen”. Within 48 hours of our departure, two of the rearmost upper containers on the port side started leaking Aviation fuel, which came as a shock to most. With no baffling of any sort fitted inside the containers, they quickly sprung multiple leak. We therefore spent most of the second night at sea hosing down aircraft and decking as Avtur rained down on us until all the remaining fuel could be pumped overboard. One spark and the ship probably would have been lost. Also Portacabins were fitted and used for the extra accomodation, not containers.

The Voyage South – When the Russian “Bear’ was sighted, the Deck Alert Sea Harrier was in the process of being launched when it was discovered that no-one on board could find the fins for the side-winders, but thats a story for the Matelot’s (Maternot!) to cover not us Crabs.

Task Force Rendevous – You might want to re-consider if Bravo November could possibly have flown off from the rear deck when next day photographs show another burnt out Chinook there when it sank. The truth is it didn’t. We debagged and bladed Bravo November first, (no mean feat at sea), which then took off and operated solely from the front deck. Our little group then started to prep all the remaining Chinooks, but it was slow going for so few people. Bravo Tango, (or Toilet), on the rear deck, was debagged, prep’d and bladed as the next due to leave. Once it’s final securing of the blade pins was complete, we took a break before starting pre-flight checks. The ship was hit, by both Exocets, yes both, definitely, before we had even finished our cuppa. Although we never got near the rear deck again because of thick acrid smoke, it might be an interestingly fact to some that despite the intricate start-up sequence normally required, Bravo Tango’s APU started all by itself as the aircraft started to burn.

Exocet – Shrapnel did came through the ship’s sides as ammunition exploded, it included several of the gas cyclinders that had been racked horizontally for transportation. All caused great concern for those climbing down the ladders when abandon ship was given.

You might want to consider adding that when MARTSU finally ejected the forward LOX tanks overboard it bizarrely saved the life of Sgt Hitchman (18 Sqn) who, unbeknown to anyone had jumped overboard from below decks as soon as the Exocets hit. Now nearly two mile adrift, aircrew circling overhead only noticed him in the water because they were watching LOX tanks bob past the burning aft of the ship.

ZA718 Bravo November – Dick Langworthy, DFC, who flew BN for the remaining conflict had a heart attack and unfortunately died in the FI, at Port San Carlos, the following year while 18 Sqn detachment commander.

Memorial – There is/was a Memorial wall to ACO built at a cove just outside Kelly’s Garden, by Port San Carlos in 1983.

Thanks to George McDonald – My own journey involved our dingy missing the bow of Alacrity, incredibly brave navy divers and finally being winched up by Wessex and being put down on Hermes. George like many on the Hermes, just freely opened up their personal lockers to give us all dry kit/snacks/drinks etc. They were all just brilliant. Annoyingly, myself and another from the Sqn should have joined BN as groundcrew when she next took off, but in the rush to clear Hermes deck as you say, it left without us.

Mrs Rosemary Anslow – My heart goes out to you. Ade was truly a great young man and so much fun. He spent a fair bit of time with our group and like the others was always up for serious inter-service banter. He is still very fondly remembered and toasted at each of our 18 Sqn groundcrew reunions.

Finally – To Colin Enticknap. To the best of our joint knowledge there were only two Royal Navy Reservists onboard. Neither were called Derek Andrews. I have a picture of all the survivors on board the British Tay and he is not on it. Checking for recipients of the Queens Gallantry medal from any point in time is easy and you will definately find it on-line if it happened. I can help you with your small piece of cloth with RNR 35474 on it, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/30147410 from the Imperial War Musuem shows it to be a pattern number sown on to identify a piece of uniform.

Once again, Thank You for recording a fine piece.

Hi Arnie, thanks for your very kind words, actually quite touched me to be honest, am glad you found it OK.

I will update the post with your feedback

An excellent piece, thanks for the original and the update. The question of defensive systems not being fitted to Atlantic Conveyor and other STUFT ships has come up many times. In fact there was nothing practical that could have been fitted that would have provided any meaningful defence. Chaff (or lack of) is often cited. However, in order to be effective the RCS return of a chaff cloud has, in simple terms, to be greater than the ship it is intended to protect. The RCS of Atlantic Conveyor was far greater than the upper limit for which chaff would have offered any benefit.

To absent friends.

I was stationed in Germany in 1982 during the Falklands War. My unit followed the deployment and combat events as closely as possible. At a dining in after it was all over, our chaplain said a prayer for our lost gallant allies, and our battalion commander raised a glass with the words, “To absent friends.”

A good refresh, just at the end lost track of G3s and G4s (unless the latter are the Points?)

This brings back lots of memories

This is Valentines day I dedicate a Rose to all my absent friends from Atlantic Conveyer.

I was a young 22 year old Radio Operator (RN) drafted onto the Atlantic Conveyer for the journey to the Falklands.

I had previously served on HMS Brilliant prior to my draft to the A/C.

My daily duties were in the Radio Office. I worked with some fantastic dedicated people and have some great memories.

Mrs Anslow I am so sorry for your loss. I loved your poem sadly I did not work on board with your son I am sure he was a wonderful person.

After the ship was struck I was one of the lucky ones to survive from the sea.

I was by coincidence eventually picked up from my dingy by HMS Brilliant my previous ship so glad to see my mates.

Hi Arnie Arnold sorry I did not work with you on board either but I would be grateful if you could contact me regarding your photograph of the survivors from British Tay. I would love a copy.

Special mention to the family of Ron Hoole we served together daily in the Radio office so sorry for your loss.

The photograph of the ships memorial on the Falklands island is very special some day I will visit.

That is one of the most detailed, well presented reports or accounts that I have ever read. I would like to complement the author. I served as a Bridge Watchkeeping Officer with the RFA, but this was well after the Falklands Conflict. In my 10 years, with the RFA, its headquarters went from North Office Block, London to the City of Bath then onwards to Portsmouth Naval Base. I was qualified additional to Bridge Watchkeeping aswell as other additional duties, as firstly an HC(like a shipborne Air Traffic Controller) and later in career as a Point Defence Officer, responsible to Command(the Commanding Officer or Ship’s Captain) for the Air Defence of respective RFAs on which I served and in that the training of, (ie the briefing, practice and safe carrying out of[coordination of]) all Live Gunnery Shoots.

In time of actual conflict(which I never encountered though was in peaceful related zones around times of conflict on some ships), I would have also manned the vessel’s AAWC as necessary, plotting, relaying zippos(ie the threat level) and all. My first ship with the RFA was RFA Regent. RFA Officers when I was with them (ending early 2000s) were for Deck and Engineering Officers core trained at Merchant Navy schools(South Tyneside College or Warsash, Southampton) and received Merchant Navy Qualifications with Royal Navy military requirements and courses filling the required gaps at Royal Navy Bases. They Occassionally overlapped, sea survival for instance, I did a course, at both in my career. The second, swimming away to shore fully clothed from a middle of lake liferaft after a further brief in it was not fun but pales obviously. We get tacbays on the Bridges of our RFAs, radio rooms immediately tending to be off the bridge and behind.

Look I cannot say much, I was a kid during the Falklands Conflict so I dont know much, one of the ships that was a Ship Taken Up from Trade was one of the North Sea Ferries, out of Hull, can’t remember which, they begin Nor(something), think I saw mention of one this piece. I remember a Sandy Nicholson in his newspaper photo showing him in his white suit(I kept a scrapbook during the conflict.) Canberra they made a big deal over, waving from the shoreside on departure. Hermes with its rounded like bulbous extending below ramp part of skiramp unlike the Invincible Class.(That knowledge is only from photos). I cannot comment on accuracy here because I was a kid then but the author has purveyed and put across accuracy and been thorough, it’s probably the best, most considered report I think I have read on anything, anywhere, ever.

It really is magnificent in its thoroughness and I apologise if its felt ill placed saying that. I personally can only relate to knowledge spent in the RFA. Initial thoughts i wondered why they were so far apart. No I haven’t been in a similar situation. I’ve, whilst with the RFA, on Ocean Passage in Company, carried out OOW Manoeuvres with War Canoes. I’ve when not exercising still on Ocean Passage with them carried out Round the Clock turn of the hour, thirty minutely(Might have even been less, think it was its been a while and fifteen or twenty minutely auto station keeping games through the night getting into station by a particular time period to assess how close we are to perfection with all the other ships, we all moving to a new sector through the night around a centrally chosen ship, before then without further orders at further allotted time past hour every hour, moving to the new sector clockwise direction to be stationed by the new time. All around a centrally chosen ship. This is all obviously after the Falklands. I came here because I wondered what the Atlantic Conveyor went down with and found your site. You say she offloaded the harriers so that would have saved a little bit of the great fiscal cost,that obviously being seperate to the sad loss of life. (Tha American variant of Harrier is the AV8B or was.)

One thing I did note in my time with the RFA, and it’s not a dig, I honestly observed fact, whilst Rolls Royce provide good, dependable engines, I taking Rases (Replenishment At Sea) as aiding in the observation but seeing OOW manoeuvres too and external to my ship, excepting the Type 42s(though I will say more), Royal Navy Ships didn’t seem designed for quick acceleration. I’ve watched countless foreign warships pull away from a RAS and accelerate away from us as if we were standing still, the Dutch ships especially; it wasn’t the case with our warships excepting the Type 42s. And even the Type 42s they’d kick up a fair bit of white smoke doing so, to me that’s not a good sign. And sorry I swear it’s the truth, it seemed to be for show and yes maybe so the foreign warships just for show but they would be going, going, still going and still going…way off into the distance. Period 90s and early 2000s. I went down to the Falklands on my 4th ship with the RFA as a Cadet Officer and that was the RFA Grey Rover. We went down with the fresh out HMS Norfolk,new at the time lead ship of the Type 23 Duke Class. She suffered mechanical difficulties on way down.

But she was fresh into service, just teething troubles i imagine and had to put into port on way down when travelling down the West side of Africa with us. We stopped at Dakar, Freetown(too I think), Tristan Da Cunha, Cape Town, and went on to the Falkland Islands where I found the Falklands had penguin colonies not far from the ship and they readily accepted humans amongst them(crouching down, they would approach even closer and peck at raised back heal of shoe). Maybe it’s important to some, maybe it’s not but Epic Games cites the accepted currency for them for the Falkland Islands as the US Dollar(their faq), I can link it if you want.

We almost, am not sure if its actually gone yet (and would be unjustly) but we almost lost Diego Garcia which has an American Naval Base and Airstrip sat upon it, it being our territory, whilst there was no mention of what would be happening to that US Naval Base in that discussion at all. Things in the World right now are not good for Britain as Britain. US Air Force Bases in Britain serve what purpose. Sorry that’s it on that issue. Not relevant you may say. A bit about surprising and realated to the Argentinians I think I read from this piece, and the fact the current British Ambassador to the UN seems more American than British in recent familiarity prior to taking up her post, I feel it may be and more than you realise. What you have provided is a good read. Boris Johnson(Doris) was born in New York.

If there’s more to say on this(your piece) you should delay until smooth sailing if speak out level other than if just felt deflection of me. Thankyou for allowing people to post comment on.

As a survivor of the Atlantic Conveyor I found the article a very interesting read. 845 NAS B Flight joined the AC on 20th May, vacating HMS Hermes to make room for the Harriers, Conveyors cargo. We brought with us two Wessex Vs, call signs Delta and Sierra. These were lost despite at least one of them being spread for flight. I was good friends with both AEM(R) Adrian Anslow and LAEM(L) Don Pryce who sadly made the ultimate sacrifice. One thing worth mentioning is the fantastic seamanship displayed by HMS Alacrity and her ship’s company, I and 76 others owe our lives to them.

Happy Conveyor Day All! I think you’ll find we had more than one beer together Colin.Muirhead, Not sure how to contact you, but more than happy to send you survivor photo from British Tay.

Hi Arnie Arnold my contact details colmyy@talktalk.net

A very pertinent piece, nice one think Defence.

Further to this piece, ZA718 Bravo November went on to serve the RAF for 39 years. It had served all over the World in exercises, operations and Wars. It was one of the original batch of HC1s that was continuously modified, right up to demob.

Thankfully the MoD, decided not to sell BN on to another Country, but instead be given as a gift to the RAF Museum at Cosford (in-between Wolverhampton and Telford). In April 2022 on the back of a low loader, the ol' girl was sent for a well deserved rest and now resides in the Museum, parked next to a a Harrier GR3 another Falklands veteran.

I don't remember where I heard it now but there's another story about the cost of losing the Atlantic Conveyor. It was carrying spares for Rapier missile batteries. There was one overlooking Bluff Cove and it detected the incoming Argentine jets. Due to lack of maintenance and spare parts, as the turret started to turn to engage them it blew a fuse and just started making a clacking sound. The Sir Galahad may have been hit as a knock-on effect from the sinking of the Conveyor.

The Horizon episode 'In the Wake of HMS Sheffield' went through arguments for not arming merchant ships, including their need to be connected to radar and computer systems, and not wanting merchant seamen firing them at everthing that moved. I though a solution would be to put the weapons on the cargo ships, but only fire them under the command of a warship. The RN ships nearby could see the missiles heading towards Atlantic Conveyor on their own radars, but were too far away to use their own missiles. If they could have signalled weapons on AC to fire, that could have made a difference. The datalink technology did exist at the time, and other RN ships did work together, using the radar of one and the missiles of the other (though they did get in each other's way at crucial moments).