Share on twitter

Twitter

Share on facebook

Facebook

Share on linkedin

LinkedIn

Share on reddit

Reddit

Share on print

Print

The Royal Navy Type 31 General Purpose Frigate (GPFF) is a new class of vessel designed to provide a lower cost vessel in the capability space between the Batch 2 River Class OPV and Type 26 Frigate.

The official history of the General Purpose Frigate (GPFF) starts with the Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) 2015.

We will maintain one of the most capable anti-submarine fleets in the world with the introduction of eight advanced Type 26 Global Combat Ships, which will start to replace our current Type 23 frigates in their anti-submarine role. We will also launch a concept study and then design and build a new class of lighter, flexible general purpose frigates so that by the 2030s we can further increase the total number of frigates and destroyers. These general purpose frigates are also likely to offer increased export potential

Although it has origins going back several years before that.

Prior to SDSR 2015

Although there may not be a direct line between the late nineties Future Surface Combatant (FSC) programme and the Type 26, there are certainly echoes of a dotted line.

Click here for a description of the history prior to SDSR 2015

The Sustained Surface Combatant Capability study concluded in 2007 that in order to meet the Future Surface Combattant requirement (to replace Type 22 and Type 23) should not be delivered by the original two-class (VSC and MSVD) solution but a new two-class solution, with an additional vessel that would replace the hydrographic, mine countermeasures and patrol ships.

Two became three;

- C1; Force Anti-Submarine Warfare Combatant, a large multi-mission combat vessel for ASW and land-attack missions.

- C2; Stabilisation Combatant, a less well-equipped vessel for chokepoint escort and protection of sea lines of communication (SLOC).

- C3; ocean capable patrol vessel

C1 and C2 would use the same hull form but have different equipment levels. C1 would be built at one per year, followed by the C2’s. The C1 and C2 concept of having the same hull but different equipment fits was eventually taken into the Type 26 Global Combat Ship.

The original concept for Type 26 was 13 vessels (8x Type 26 with Sonar 2087 for ASW and 5 x Type 26 without Sonar 2087 for General Purpose)

Thales proposed a C3 vessel called the Modular General Purpose Frigate and VT, another concept based on their earlier Global Corvette for the C3 requirement, called the Ocean Capable Patrol Vessel (OCPV)

The VT vessel was based on its design for the Royal Navy of Oman but with more equipment space, taking its displacement up to 3,000 tonnes. It could travel at a top speed of 25 knots, accommodate a crew of 76 and carry a number of ISO containers underneath the Merlin capable flight deck. This design would eventually feature in early concepts for the Type 31

BAE Surface Ships were awarded a four-year, £127m, contract in 2010 to design the Type 26 Global Combat Ship.

The baseline design suggests a 141m long vessel, displacing 6,850 tonnes equipped with a towed low frequency sonar array and two launchers for the Future Local Area Air Defence (Maritime) system firing the Common Anti Air Modular Missile. Other options include a vertical launch system for Tomahawk, SCALP or a modified GMLRS. Harpoon and a main gun also remain options, a choice of 127mm, 155mm or even a refurbished 114mm weapon. Aviation facilities include a Chinook flight deck and hangar for a Merlin and UAV, the UAV possibly housed in a supplementary ‘dog kennel’ hangar. Beneath the flight deck will be a large mission bay and stern dock to hold 4 9m RHIB’s, a torpedo system and a wide variety of mission modules. It is also anticipated that the Type 26 will have an either all electric or hybrid electric propulsion system providing a range of 7000nm at 18 knots. The ship’s complement is expected to be in the region of 150 plus an embarked force of over 30

The C1 and C2 variants of FSC had variously flip-flopped between completely different designs and identical base hulls with different equipment fits over the course of the elongated FSC programme but SDSR 2010 confirmed it would be met by a single acoustically quiet class of vessel, the Type 26 Global Combat Ship.

SDSR 2010 also described how Frigate numbers were to be reduced to 13, the Type 22’s being withdrawn. Eight Type 26 would be designated Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) variants and five, General Purpose (GP).

In various public appearances, 1SL and other Royal Navy Very Senior Officers would insist that only a one-for-one replacement of Type 23 with Type 26 would deliver the credibility and capability the UK needed. They were uniformly emphatic and anecdotally, any suggestion of a two-tier fleet or more OPV’s/Corvettes would be extremely unwelcome.

At the end of September 2015, Defense News reported a comment by Rear Admiral Alex Burton, Assistant Chief of Naval Staff (Ships);

Burton put a price tag of £12 billion on what is currently a 13 frigate program aimed at replacing the Royal Navy’s aging Type 23 anti-submarine/general purpose fleet starting 2023 when HMS Argyll is retired. The figure is not the exact cost for the program but was meant to give the audience a feel for the size of the program versus other projects, said a MoD source. The figure had been rounded up by Burton and the true cost was closer to £11.5 billion, they said. The source said the figure was an outturn price for a program expected to run into the 2030’s and not the cost at current prices

This, of course, set the hares and hounds running with extrapolations made to get unit cost. A financial consultancy services contract was advertised to provide additional support to the decision-making process.

[the_ad id=”53393″]

Clearly, all was not well in the Type 26 GCS Programme.

As covered in the Type 26 history and further up the page, the Royal Navy had implacably set its face against a two-tier frigate fleet, indeed, it was widely reported that Admiral Sir Gorge Zambellas would have an ‘allergic reaction’ to anyone mentioning the C-word, corvette.

In an interview for Jane’s in 2015, he said;

One of the siren calls I completely resist is to try and produce something that is not a credible platform, something that is smaller, cheaper, and less effective. The reason for that is that in the first world that I live in, credible capability could one day be doing counter-piracy operations, the next week it could be in a hot war in the Gulf, and the week after in a hot war somewhere else.

The 2015 SDSR was by now coming into view.

After SDSR 2015

The 2015 SDSR, published in November 2015 described a change of plan for Type 26.

We will maintain one of the most capable anti-submarine fleets in the world with the introduction of eight advanced Type 26 Global Combat Ships, which will start to replace our current Type 23 frigates in their anti-submarine role. We will also launch a concept study and then design and build a new class of lighter, flexible general purpose frigates so that by the 2030s we can further increase the total number of frigates and destroyers. These general purpose frigates are also likely to offer increased export potential.

No longer were there to be 13 Type 26 split between 8 ASW and 5 GP, the Type 26 programme would be truncated at the eight ASW variants. It also confirmed a further two River Class Batch II vessels would be purchased to fill in the widening gap between the end of the QE carriers build and the start of the Type 31/26 frigates. The SDSR also stated that there would be ‘up to six’ OPV’s in-service and subsequent speculation was that this would consist of the 5 new builds and the existing modified batch 1, HMS Clyde, with the original Batch 1 vessel withdrawn.

The first Google entry for Type 31 as a possible class name was none other than yours truly on November 27th 2015 :)

In July 2016, in a speech at Mansion House, 1SL, Admiral Sir Philip Jones referred to the GPFF as Type 31.

Meanwhile our current Type 23 frigates, the backbone of the Fleet, will be replaced with 8 Type 26 anti-submarine warfare frigates and “at least” 5 lighter Type 31 General Purpose frigates. The build programme for the Type 31, and subsequent classes of ship, will be determined by the National Shipbuilding Strategy which is being developed by Sir John Parker and is expected to report later in the year.

Within this Strategy is the opportunity to both strengthen our security overseas and also invest in Britain’s prosperity at home. Type 26 is a case in point. The hull may be built on the Clyde, but the benefits are shared across the country. It includes gearboxes from Huddersfield, stabilisers from Dunfermline and countermeasures from Bridgend: high-tech systems that demand high-skilled jobs and create new apprenticeships.

The Type 31 offers the same prospect; but with an additional potential for export orders for the UK from the international market. The National Shipbuilding Strategy therefore represents a historic opportunity to reverse the decades old decline in surface ship numbers, and to re-establish a sustainable and prosperous long term shipbuilding capability that sits above short term economic and political tides.

There will be challenging trade-offs to achieve in order to keep the price down, and the timescale is tight. But if we get this right, and I am determined that we will, then there is a real chance to grow the size of the Royal Navy’s fleet for the first time in decades.

This could enable a more frequent, or even a permanent, presence in parts of the world where we have admittedly been spread thin in recent decades. Together with the aforementioned naval base in Bahrain, the Royal Navy has also been working with the government of Oman to explore berthing options in the new commercial port of Duqm. Situated outside the Strait of Hormuz it provides immediate access to the Indian Ocean and capacity for aircraft carriers and nuclear powered submarines. Under the Five Powers Defence Agreement, the Royal Navy also retains berthing space in Singapore.

All of these facilities provide the government and defence with the option, should we wish, to project power and influence beyond the Atlantic. Given our long standing defence relationships in the Middle East, it is certain that a Royal Navy task group, centred on a Queen Elizabeth-class carrier, will regularly deploy East of Suez. And it will be perfectly possible, should we wish, for Type 31 frigates to permanently operate from the Gulf region or from Asia-Pacific in the decades ahead.

The same evidence session also saw 1SL confirm that the SDSR 2015 description of ‘up to six’ OPV’s actually meant five, with HMS Clyde replaced by one of the five new builds. HMS Forth, the first of the five River Class Batch 2 vessels was floated out in August 2016.

The River Class has been somewhat of an unlikely success with 13 built (or about to be built) and a further 3 derivatives.

Perhaps the most significant event in the history of Type 31 was the publication of the National Shipbuilding Strategy (Independent Report) by Sir John Parker in November 2016. This was originally described as the national shipbuilding strategy but was later downgraded to an independent report that would inform the actual strategy.

Sir John made a number of observations and judgement statements about the woes and on Type 31, or General Purpose Frigate made four recommendations;

13.

The new Type 31e should not set out to be a complex and sophisticated warship based on traditional design approaches. It should be a modern and innovative design on a standard platform which should provide a menu of choice to support exports and beat the competition. It should be termed Type 31e. The ‘e’ means that export flexibility is inbuilt, not a variant

14.

The Type 31e should be prioritised, and act as a pathfinder project to pilot this new governance and Virtual Shipbuilding (VSb) industry approach (see recommendation 19 and Figure 4). It should be rapidly procured and placed into service as early as possible in the 2020s. If necessary, wider Government financial support should be provided to allow early build of the vessel. This will enable the new governance approach to be embedded in order to deliver medium to long-term savings in ship procurement

15.

Type 31e should be designed so that the price/capability point is an attractive export proposition and then it should be delivered to a hard target cost

16.

The MOD should determine the optimum economic service life for a naval ship and then replace ships with new vessels at that point, rather than operate longer and thus avoid expensive major refits. As a pathfinder, Type 31e should also be procured as a RN asset that stimulates exports including via sales from the Fleet

An evidence session on the National Shipbuilding Strategy at the House of Commons on the 28th of February 2017 revealed the working assumption that Type 31 is being referred to as Type 31e, e for export, as in the report. It also became clear that the desire for Type 31 is that it is built in parallel with Type 26 in order to prevent a reduction in frigate numbers between 2023 and 2035.

The Defence Select Committee released their third report of the 2016/17 Session called Restoring the Fleet. It highlighted that the oldest Type 23 is due out of service in 2023 (HMS Argyle) with the rest following as Type 26 comes into service although the MoD has not published how this may be integrated with Type 31.

| Ship Name | Out of Service Date |

| HMS Argyll | 2023 |

| HMS Lancaster | 2024 |

| HMS Iron Duke | 2025 |

| HMS Monmouth | 2026 |

| HMS Montrose | 2027 |

| HMS Westminster | 2028 |

| HMS Northumberland | 2029 |

| HMS Richmond | 2030 |

| HMS Somerset | 2031 |

| HMS Sutherland | 2032 |

| HMS Kent | 2033 |

| HMS Portland | 2034 |

| HMS St Albans | 2035 |

One of the significant issues with commenters understanding of Type 31 was its positioning. Clearly, this was a cost-based decision. Before cost negotiations had been finalised on Type 26, the MoD had decided that the cost of…

FIVE GP TYPE 26 > FIVE TYPE 31

It was as simple as that.

It is worth a reminder of the MoD’s approach to defining the acquisition of major projects, CADMID (Concept, Assessment, Manufacture, In-Service and Disposal) Following this means that the CADM elements of Type 31 have to be less than the M element for 5 GP Type 26, as the diagram below shows.

In extrapolating the cost envelope for Type 31 GPFF many made the assumption that it was between £2.5 Billion and £5 billion, and if it is cheaper then it will satisfy the requirements that Type 31 GPFF was lower than the cost of Type 26 but having a better specification than a £130 odd million Batch II River Class OPV. Although some pre-concept work had been carried out by the Maritime Capability (MARCAP) inside Naval Command Headquarters (NCHQ) what made this difficult was the ongoing uncertainty on the Manufacture contract for Type 26 AND the National Shipbuilding Strategy, scheduled for publication in 2017.

Jane’s reported that the expected cost per vessel was £275 million to £375 million. Credibility is a nebulous concept, all we could say for certain at that point in time was that the Type 31 GPFF would exist on a point between the Batch II River Class OPV and the Type 26 Frigate.

In the middle, trade-offs between capability, cost and quantity.

In a speech by Admiral Sir Philip Jones, First Sea Lord, on the 7th of September 2017, the entry into service date for Type 31 was linked to the withdrawal of HMS Argyll, one of the general-purpose Type 23’s.

Minister, ladies and gentlemen, it’s a pleasure to speak to you today, in the midst of a hugely exciting few weeks for the Royal Navy and the UK’s maritime industrial sector.

As the minister mentioned, when HMS Queen Elizabeth arrived in Portsmouth last month, I described it as a triumph of strategic ambition and a lesson for the future, and I really meant it. Here was a project first initiated 20 years ago, in which time it outlasted 3 prime ministers, 8 defence secretaries and 7 First Sea Lords. It survived 5 general elections, 3 defence reviews and more planning rounds than I care to remember. But despite all these twists and turns, the project endured and, in doing so proved to the world, and to ourselves, that we still have what it takes to be a great maritime industrial nation.

Now, in the National Shipbuilding Strategy, we have an opportunity to maintain the momentum.

So my reason for being here today is two-fold. Firstly, to outline the Royal Navy’s requirement for the Type 31e by describing the kind of ship we’re looking for and it’s place in our future fleet. Secondly, to emphasise our commitment to working with you, our industry partners, to build on what we’ve achieved with the Queen Elizabeth class, and to bring about a stronger and more dynamic shipbuilding sector which can continue to prosper and grow in the years ahead. The Royal Navy’s requirement for a general purpose frigate is, in the first instance, driven by the government’s commitment to maintain our current force of 19 frigates and destroyers.

The 6 Type 45 destroyers are still new in service, but our 13 Type 23 frigates are already serving beyond their original design life. They remain capable, but to extend their lives any further is no longer viable from either an economic or an operational perspective. Eight of those Type 23s are specifically equipped for anti-submarine warfare and these will be replaced on a one-for-one basis by the new Type 26 frigate.

As such, we look to the Type 31e to replace the remaining 5 remaining general purpose variants.

This immediately gives you an idea of both the urgency with which we view this project, and how it fits within our future fleet. In order to continue meeting our current commitments, we need the Type 31e to fulfil routine tasks to free up the more complex Type 45 destroyers and Type 26 frigates for their specialist combat roles in support of the strategic nuclear deterrent and as part of the carrier strike group.

So although capable of handling itself in a fight, the Type 31e will be geared toward maritime security and defence engagement, including the fleet ready escort role at home, our fixed tasks in the South Atlantic, the Caribbean and the Gulf, and our NATO commitments. These missions shape our requirements.

There is more detail in your handout but, broadly speaking, the Type 31e will need a hanger and flight deck for both a small helicopter and unmanned air vehicle, accommodation to augment the ship’s company with a variety of mission specialists as required, together with stowage for sea boats, disaster relief stores and other specialist equipment.

It will be operated by a core ships company of between 80-100 men and women and it needs to be sufficiently flexible to incorporate future developments in technology, including unmanned systems and novel weaponry as they come to the fore, so open architecture and modularity are a must.

All this points towards a credible, versatile frigate, capable of independent and sustained global operations. Now I want to be absolutely clear about what constitutes a frigate in the eyes of the Royal Navy.

In Nelson’s time, a first rate ship like HMS Victory was a relative scarcity compared with smaller, more lightly armed frigates. They wouldn’t take their place in the line of battle, but they were fast, manoeuvrable and flew the White Ensign in many of the far flung corners of the world where the UK had vital interests. More recently, the navy I joined still had general purpose frigates like the Leander, Rothesay and Tribal class and, later, the Type 21s, which picked up many of the routine patrol tasks and allowed the specialist ASW frigates to focus on their core NATO role.

It was only when defence reductions at the end of the Cold War brought difficult choices that we moved to an all high end force. So forgive the history lesson, but the point I’m making is the advent of a mixed force of Type 31 and Type 26 frigates is not a new departure for the Royal Navy, nor is it a ‘race to the bottom’; rather it marks a return to the concept of a balanced fleet.

And the Type 31e is not going to be a glorified patrol vessel or a cut price corvette. It’s going to be, as it needs to be, a credible frigate that reflects the time honoured standards and traditions of the Royal Navy. In order to maintain our current force levels, the first Type 31e must enter service as the as the first general purpose Type 23, HMS Argyll, leaves service in 2023.

Clearly that’s a demanding timescale, which means the development stage must be undertaken more quickly than for any comparable ship since the Second World War.

But while this programme may be initially focused on our requirements for the 2020s, we must also look to the 2030s and beyond. You know how busy the Royal Navy is and I won’t labour the point, suffice to say international security is becoming more challenging, threats are multiplying and demands on the navy are growing. Added to this is that, as we leave the European Union, the UK is looking to forge new trading partnerships around the world.

Put simply, Global Britain needs a global Navy to match.

It is therefore significant that the government has stated in its manifesto, and again through the National Shipbuilding Strategy, that it views the Type 31e as a means to grow the overall size of the Royal Navy by the 2030s. If we can deliver a larger fleet, then we can strengthen and potentially expand the Royal Navy’s reach to provide the kind of long term presence upon which military and trading alliances are built.

This is a hugely exciting prospect, but we must first master the basics. We can all think of examples of recent projects which have begun with the right intentions, only for timescales to slip, requirements to change and costs to soar. As Sir John Parker highlighted in his report last year, we end up with a vicious cycle where fewer, more expensive, ships enter service late, and older ships are retained well beyond their sell by date and become increasingly expensive to maintain. So we need to develop the Type 31e differently if we’re going to break out of that cycle.

We’ve said that the unit price must not exceed £250 million.

For the Royal Navy, this means taking a hard-headed, approach in setting our requirements to keep costs down, while maintaining a credible capability, and then having the discipline to stick to those requirements to allow the project to proceed at pace. It also means playing our part to help win work for the UK shipbuilding sector from overseas. So the challenge is to produce a design which is credible, affordable and exportable.

Adaptability is key, we need a design based on common standards, but which offers different customers the ability to specify different configurations and capabilities without the need for significant revisions. So while it may be necessary to make trade offs in the name of competitiveness, export success means longer production runs, greater economies of scale and lower unit costs, and therein lies the opportunity to increase the size of the Royal Navy.

With a growing fleet it would be perfectly possible for the Royal Navy to forward deploy Type 31e frigates to places like Bahrain Singapore and the South Atlantic, just as we do with some of our smaller vessels today.

If our partners in these regions were to buy or build their own variants, then we could further reduce costs through shared support solutions and common training. And because of the Royal Navy’s own reputation as a trusted supplier of second hand warships, we could look to sell our own Type 31’s at the midpoint of their lives and reinvest the savings into follow-on batches. So by bringing the Royal Navy’s requirements in line with the demands of the export market, we have the opportunity to replace the vicious circle with a virtuous one.

And beyond the Type 31e, the benefits could apply to the Royal Navy’s longer term requirements, beginning with the fleet solid support ship but also including our future amphibious shipping and eventually the replacement for the Type 45 destroyers as well as other projects that may emerge. Ultimately, the prize is a more competitive and resilient industrial capacity: one that is better able to withstand short term political and economic tides and can serve the Royal Navy’s long term needs.

So, in drawing to a close, I believe we have a precious opportunity before us.

My father worked at the Cammell Laird shipyard for over 40 years. It was visiting him there as a schoolboy and seeing new ships and submarines taking shape that provided one of the key inspirations for me to join the Royal Navy, nearly 40 years ago. And yet, for most of my career, the fleet has become progressively smaller while the UK shipbuilding sector contracted to such an extent that it reached the margins of sustainability. But with the Queen Elizabeth class carriers, and the 6 yards involved in their build, we demonstrated that shipbuilding has the potential to be a great British success story once again. Far beyond Rosyth, we’ve seen green shoots emerging in shipbuilding across the country, and throughout the supply chain, driven by a new entrepreneurial ambition.

Now the National Shipbuilding Strategy has charted a bold and ambitious plan to capitalise on that and reverse the decline. And in the Type 31e, we have the chance to develop a ship that can support our national security and our economic prosperity in the decades to come.

The navy is ready and willing. Now we look to you, our partners in industry, to bring your expertise, your innovation and your ambition to bear in this endeavour.

The MoD published a request for information on the 15th of September 2017 for Type 31e, describing the timelines to service entry in 2023.

A number of initial concepts were released by bidders towards the end of 2017

BAE Cutlass

Derived from the Project Khareef Corvette, the Cutlass design was 117m long.

The image showed an ARTISAN radar and 5″ main gun, with covered spaces for small craft. Additional improvements include much-improved survivability, greater endurance and an ability to be replenished at sea.

BAE Avenger

At a lower price/capability point than Cutlass, the Avenger was more or less and stretched and improved Batch II River Class

The 111m Avenger was longer and wider than a Batch II River Class OPV that allowed for a small hangar and space/launch and recovery systems for a number of small and unmanned craft. The image also seemed to show ARTISAN radar and a Mk 45 Mod 4 5″ main gun for naval gunfire support.

BMT Venator 110

The MT Venator concept had been evolving for some time, the latest at that point being Venator 110.

Ventator 110, was 117m long, displaced 4,000 tonnes, had a top speed of >25 knots and featured a large flexible mission bay.

BMT also released a video.

Steller Systems Project Spartan

A small design house, Steller Systems, proposed a design called Project Spartan.

The Nodal Modular Physical Architecture approach to the design allowed for configurable options.

Babcock Arrowhead 120

The last of the publically marketed concepts was from Babcock, for their Arrowhead 120 design.

The Arrowhead 120 and Spartan seemed like similar concepts.

At an industry event, the MoD outlined a set of broad requirements.

Click to access 20170901-T31e-Launch-Folder-line-diagram-V4-1.pdf

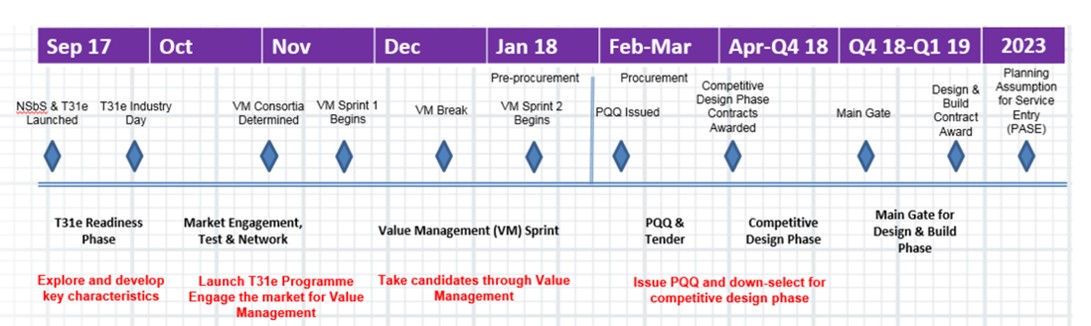

Timelines were additionally described in a written answer in October 2017

Pre-procurement activity with industry has begun and will continue into early 2018 when we plan to formally start the competitive process. We plan to award a single design and build contract in 2019, allowing us to trial and accept the first ship into service in 2023.

A follow-up question confirmed the £250m price limit and after the receipt of 22 expressions of interest, again confirmed the £250m price limit.

Babcock, BMT and Thales announced in November 2017 they would partner to meet the Type 31 requirements which by May, would lead them to conclude an evolved version of the Danish Iver Huitfeldt class frigate would be best placed.

Thales press release confirming the Arrowhead 140;

Babcock Team 31 has today unveiled Arrowhead 140 as its design for the UK Ministry of Defence’s (MOD) new £1.25 billion Type 31e general purpose light frigate programme.

Launching the new platform, ‘Team 31’ – led by Babcock and including fellow industry experts Thales, OMT, BMT, Harland and Wolff and Ferguson Marine – underlined the vessel’s established, ‘at sea’ design baseline which can be developed to meet global requirements.

With UK engineering at its core, and developing OMT’s Iver Huitfeldt hull form currently in-service for the Royal Danish Navy, Arrowhead 140 will lower programme risks through its tried and tested baseline design and is engineered to minimise through-life costs whilst delivering a truly leading edge frigate. Craig Lockhart, Babcock’s Managing Director, Naval Marine said: “Arrowhead 140 is a proven, capable, and adaptable general purpose frigate design that, if selected, will meet the UK Royal Navy’s and global customers’ expectations both now and in the future.”

At almost 140m the platform will optimise operational flexibility. This ‘wide beam’ ship is easier to design, easier to build and easier to maintain due to its slightly larger size. And with embedded iFrigate™ technology able to deliver digitally enabled through life support, it offers extensive value for money – all within the same budget. Craig Lockhart said: “Arrowhead 140 will provide increased survivability, operability and capability – compared to a standard 120m design. When you consider that this ship can be delivered at no extra cost and that it will support improved radar performance, increase platform stability and facilitate better helicopter operations in bad weather, whilst enhancing crew comfort – we believe it will bring a significant edge to modern naval capability.”

Arrowhead 140’s distributed build and assembly approach, comprising Babcock Appledore in North Devon, Ferguson Marine on the Clyde, Harland and Wolff in Belfast with integration at Babcock Rosyth, Fife, optimises the partners’ first-class UK facilities, innovation and skills whilst cleverly ensuring capacity for parallel programmes remains. All of which is geared to generate a genuine resurgence in shipbuilding across the UK and when coupled with the virtual design alliance between Babcock, OMT and BMT it squarely supports the intent of the National Shipbuilding Strategy.

Craig Lockhart continued: “More than just building a ship, Babcock Team 31 offers a unique opportunity for global navies to tap into the complete design, build and support capability for the T31e frigate. Individually all of the Babcock Team 31 members have exceptionally strong portfolios of activity and collectively we are able to introduce to the market Arrowhead 140; a general purpose light frigate package that we believe is second to none.”

Incorporating the latest iteration of Thales’ TACTICOS combat management system with fully open architecture sets Arrowhead 140 combat systems apart. Currently in service for 25 years and exported to 24 navies globally, this system and equipment in-service support package is flexible to customers’ needs over the lifetime of the platform and will maximise the combat system capability for customers. It is a system that has time and time again proven to be a leading edge solution for navies fighting tomorrow’s war.

And with extensive procurement required throughout the lifetime of the project, opportunities predominantly for UK based small to medium sized enterprises will be available to help to meet time, costs and quality standards. Interest is already strong in Team 31’s bid with more than 100 supply companies meeting Team 31 representatives at a Society of Maritime Industries facilitated suppliers’ conference in Fife.

Based on Arrowhead 140, Team 31 can build modern platforms that navies can use to tailor to their own specifications and when you add world leading experience in naval platform in-service support with a deep understanding of support cost drivers, Babcock Team 31 offers a glimpse into an exciting new world of UK and international ship build delivery and intelligent ship support with Arrowhead 140.

The MoD confirmed the estimated addressable market for Type 31e in early 2018

With reference to the National Shipbuilding Strategy no Departmental objective has been set for the export of 40 Type 31e frigates. The Government has assessed that there is a potential light frigate market of around 40 ships over the next 10 years.

The MoD suspended the Type 31 bid process on the 24th of July 2018 due to ‘inadequate competition’ but restarted it three weeks later, issuing a contract notice on the 14th of August 2018

Short description of the contract: As announced in the National Shipbuilding Strategy (“NSbS”) the Ministry of Defence (“MOD”) is seeking to procure five (5) new General Purpose Frigates for the Royal Navy (“RN”) for a total cost not to exceed £1.25 billion inclusive of Government Furnished Equipment (GFE). These General Purpose Frigates have been denoted the Type 31e (T31e).

The T31e will provide an enduring and continuous worldwide maritime security presence in forward operating areas and releasing other, more complex warships to their primary roles. The T31e will carry out maritime security and interdiction tasks, such as security patrols, escort duties, counter drugs and counter piracy. It will also carry out defence engagement activities, such as port visits and official entertainment, demonstrations of military capability and participation in allied training exercises. It must be ready to respond to emergent events, such as natural disasters or evacuation of non-combatants and will routinely carry specialist emergency relief stores in certain operating areas.

The T31e design will need to be adaptable, providing evolution paths for future capability insertion to enable growth of the destroyer and frigate numbers into the 2030s, and to address export customers’ needs. The Authority previously commenced a competition for this requirement in February 2018 with the publication of Contract Notice reference TKR-2018222-DCB-11953582. Subsequently the Authority elected to stop this procurement due to inadequate competition prior to awarding Competitive Design Phase (CDP) contracts.

The purpose of this Prior Information Notice (PIN) is to invite potential suppliers to a short period of early market engagement prior to the commencement of a new competition for the T31e requirement (“the New Procurement”). The New Procurement is planned to consist of:

1. A Pre-Qualification Questionnaire;

2. CDP Contracts for the supply of specific design deliverables during the Design & Build (D&B) competition; and

3. A single D&B Contract to build five T31e frigates for the Royal Navy.Type 31e requirement

The Authority’s high level requirement for Type 31e, in accordance with the NSbS, is for:

five (5) Type 31e ships with a target of the first ship entering into service in 2023 and the fifth ship entering into service in 2028;

a cost to the Authority (inclusive of GFE) of £1.25BN;

an open and adaptable whole ship and combat system design;

a UK focused Design and Build strategy which maximises UK prosperity and is built in a UK shipyard; and

a ship design with export potential to the global market.

Suppliers should only respond if they are (themselves or as part of a consortium with other suppliers) in a position to undertake the full Type 31e programme, meeting its full requirement including a £1.25bn cost and building the T31e in a UK shipyard.

By the end of 2018, three bids had been submitted to the MoD, each having been supported by the MoD with their bid costs.

Team Leander, a joint BAE/Cammel Laird design based on an evolved Khareef design

Atlas Electronik/Thyssen Krupp with a design based on the Meko 200 in service with the South African Navy

BMT, with their Arrowhead 140 design, based on the Danish Iver Huitfeldt class frigate

The role for Type 31e was confirmed in a March 2019 Written Answer

The Type 31e Frigates will be tailored toward maritime security and defence engagement, including the Fleet Ready Escort role at home, our commitments in the South Atlantic, the Caribbean and the Gulf, and to NATO. These ships will fulfil routine tasks to free up the more complex Type 45 Destroyers and Type 26 Frigates for their specialist combat roles in support of the strategic nuclear deterrent and as part of the carrier strike group.

The Government again confirmed a £250 price ceiling.

Three bids were received by the MoD by the end of June 2019 after a 7 month Competetive Design Phase bid process.

The Government confirmed the Preferred Bidder for Type 31e in September 2019, it was to be Babcock.

Babcock Team 31 has been selected by the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD) as the preferred bidder to deliver its new warships. Led by Babcock, the Aerospace and Defence company, and in partnership with the Thales Group, the T31 general purpose frigate programme will provide the UK Government with a fleet of five ships, at an average production cost of £250 million per ship.

Following a comprehensive competitive process, Arrowhead 140, a capable, adaptable and technology-enabled global frigate will be the UK Royal Navy’s newest class of warships, with the first ship scheduled for launch in 2023. At its height the programme will maximise a workforce of around 1250 highly- skilled roles in multiple locations throughout the UK, with around 150 new technical apprenticeships likely to be developed. The work is expected to support an additional 1250 roles within the wider UK supply chain.

With Babcock’s Rosyth facility as the central integration site, the solution provides value for money and squarely supports the principles of the National Shipbuilding Strategy. It builds on the knowledge and expertise developed during the Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier modular build programme. The announcement follows a competitive design phase where Babcock Team 31 was chosen alongside two other consortia to respond to the UK MOD’s requirements.

Work on the fleet of five ships will begin immediately following formal contract award later this financial year, with detailed design work to start now and manufacture commencing in 2021 and concluding in 2027.

Archie Bethel, CEO Babcock said:

“It has been a tough competition and we are absolutely delighted that Arrowhead 140 has been recognised as offering the best design, build and delivery solution for the UK’s Royal Navy Type 31 frigates. “Driven by innovation and backed by experience and heritage, Arrowhead 140 is a modern warship that will meet the maritime threats of today and tomorrow, with British ingenuity and engineering at its core. It provides a flexible, adaptable platform that delivers value for money and supports the UK’s National Shipbuilding Strategy.”

Arrowhead 140 will offer the Royal Navy a new class of ship with a proven ability to deliver a range of peacekeeping, humanitarian and warfighting capabilities whilst offering communities and supply chains throughout the UK a wide range of economic and employment opportunities. A key element of the Type31 programme is to supply a design with the potential to secure a range of export orders thereby supporting the UK economy and UK jobs. Arrowhead 140 will offer export customers an unrivalled blend of price, capability and flexibility backed by the Royal Navy’s world-class experience and Babcock looks forward to working closely with DIT and MOD in this regard.

Arrowhead 140 is a multi-role frigate equipping today’s mariner with real-time data to support immediate and complex decision-making. The frigate is engineered to minimise through-life costs whilst delivering a truly leading-edge ship, featuring an established, proven and exportable combat management system provided by Thales.

Victor Chavez, Chief Executive of Thales in the UK said:

“Thales is delighted to be part of the successful Team 31 working with Babcock and has been at the forefront of innovation with the Royal Navy for over 100 years. “With the announcement today that Arrowhead 140 has been selected as the preferred bidder for the new Type 31e frigate, the Royal Navy will join the global community of 26 navies utilising the Thales Tacticos combat management system. Thales already provides the eyes and ears of the Royal Navy and will now provide the digital heart of the UK’s next generation frigates.”

Babcock will now enter a period of detailed discussions with the MOD and supply chain prior to formal contract award expected later this year.

Video

Initial Operating Capability is planned to be 2027. The build for Type 31 will take place at a new covered facility at Rosyth.

Babcock released subcontract, systems and progress updates throughout 2020.

Babcock produced an update video in October 2020

In May 2021, it was announced Type 31 would be named the Inspiration Class, comprising HMS Active, HMS Bulldog, HMS Campbeltown, HMS Formidable and HMS Venturer.

HMS Active: Named after the Type 21 frigate HMS Active which served the Royal Navy from the late 1970s until the mid-1990s. As well as taking part in the operation to liberate the Falklands, supporting the final battles for Port Stanley, Active spent her career deployed in support of Britain’s Overseas Territories and global interests, from tackling drug traffickers to enforcing UN embargos and providing humanitarian aid in the aftermath of natural disasters.

HMS Bulldog: Named after the destroyer which helped turn the tables in the Battle of the Atlantic thanks to the bravery of her boarding party. They searched stricken U-boat U110 in May 1941 and recovered the Germans’ ‘unbreakable’ coding machine, Enigma, plus codebooks. It gave Britain a vital intelligence lead at a key stage in the struggle to keep its Atlantic lifelines open.

HMS Campbeltown: Named after the wartime destroyer which led the ‘greatest commando raid of all’: St Nazaire in France. In March 1942, the ship rammed the dock gates and hidden explosives aboard blew up, wreaking havoc in the port and denying its use to major German warships for the rest of WW2. The action epitomises the raiding ethos driving the Royal Marines’ Future Commando Force.

HMS Formidable: Named after the WW2 carrier which epitomised carrier strike operations from Norway, through the Mediterranean to the Pacific. She survived kamikaze strikes and took the war to the Japanese mainland with Lieutenant Commander Robert Hampton Gray earning the last naval VC of the war for his daring sinking of a Japanese destroyer just six days before Tokyo surrendered.

HMS Venturer: Named after the WW2 submarine which sank German U-boat U864 northwest of Bergen, Norway, on February 9 1945 – while both vessels were submerged. Venturer enjoyed a technological and intelligence advantage over her foe thanks to decoded messages indicating the enemy’s location and a superbly-trained crew who located and destroyed the U-boat. It was the first time one submarine had deliberately sunk another while submerged.

Currently, expected timescales are that the first ship will enter service in 2027 (the same year as the first Type 26) with the final ship in service by the end of 2030. This is a slippage of 4 years from that originally described.

The Government Furnished Equipment (GFE) was excluded from the bid process after an adverse reaction from the bidders and so the total cost (as of 2021) for each vessel will be £268 million.

[the_ad id=”53393″]Type 31 Frigate Capabilities

Type 31 will have capabilities and capacities as described in the image below

Crew size is particularly notable, 105 compared to approximately 185 for Type 23, a significant saving for a cash tight organisation. The ‘i-Frigate’ capability as described by Babcock is claimed to offer significant costs savings through predictive maintenance as well.

The 57mm main armament will be new to the Royal Navy, as will the 40mm

Type 31 will also use the Tacticos Combat Management System from Thales

Air defence missile system will be the MBDA Sea Ceptor .

Table of Contents

[adinserter block=”2″]

[adinserter block=”1″]

Change Status

| Change Date | Change Record |

| 08/09/2016 | Initial issue |

| 24/07/2021 | Update and content refresh |

Read more

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

I do not think they’ll be much debate over the FIGS role. In my view with HMS Proector lacking the hangar capability of HMS Endurance, have a River with a hangar is a reasonable request.

Also, the 1SL has already stated that the future Rivers could be used for APT(S). For such a role, given the likely scenario of rescuing sailors in distress or supporting our BOTs, then again helicopter capability should be insisted on.

It’s interesting that the 1SL did not mention WIGS as a possible future River role. It could be that there have been issues with the Batch 1 vessels supporting this role, or more likely it is assumed that they will continue to do it (rotating with a RFA). Firstly, I’d say then that with this role 5 OPVs is not enough. Secondly, surely forward basing a ship to be there 100% of the time and releasing a RFA for broader duties given the strech makes sense.

Bad reporting?

Not type 31 related strictly, personally I’d have thought it the ideal ship to send assuming it’s got choppers, ribs and plenty of marines onboard?

http://www.defense-aerospace.com/articles-view/release/3/178021/lacking-frigates%2C-royal-navy-deploys-lsd-on-med-patrol.html

Jane’s says the French are going after the African market with a 95m multi role ship armed with 30mm + .50 cal + room for 20 containers. Your dream ship that is not a frigate perhaps TD?

So, Leander or Type 21 as inspiration? Leander for names, without question. Maybe chuck a bit of LCS into the mix for good measure.

So the news today, says the government will definitely order the 8 T26 by next Summer. We shall see.

http://www.defensenews.com/articles/construction-date-set-for-british-type-26-anti-sub-frigates

“A BAE spokeswoman wasn’t able to give the planned, in-service date for the first vessel.

However, the spokeswoman gave some indication of the intended delivery rate, saying the work on the second of the 7,000-ton warships is scheduled to start around 25 months after cutting of steel on the first vessel. The third ship will follow 20 months after that, before the program settles into an 18-month drumbeat of delivery. ”

Also talks of potential to build the T31s on a modular basis at different yards and then assemble on the Clyde. That would seem to me to conflict with the exclusivity provisions of ToBA, which on the face of it say that all FFs and DDs have to be built by BAES…

Although all the Type-31 designs appear to have 30mm guns, only the most expensive includes a CIWS.

Do the designers like ignoring the Anti-Ship Missile (ASM) threat?

Relying on a batch of SAM’s to deal with all air threats is fine, until the supply has been used up, which would be quickly in any confrontation or basic saturation attack.

The current Type-23 has no CIWS, why should this mistake not be rectified in the new Type-31’s?

Even the old Type-21 Amazon class, though small, have been fitted with a Phalanx CIWS by there new owners – the Pakistani Navy.

We are supposed to learn from the mistakes of the past, ASM’s (especially when synchronised and used in numbers) are one of the most lethal threats.

(That said, I still don’t understand why the Type-45’s do not have four CIWS as a minimum).

Janes is saying the Royal Navy will retire its block 1c Harpoon, by the end of 2018, with no replacement planned in the short term.

The budget committee of the German parliament has just approved 1.5 billion euros for 5 new K130 corvettes, according to defensenews.

TYPE 31 versus TYPE 26 Lite.

The only reason for the Type 31s instead of more Type 26s is cost.

As the Type 31 is to be cheaper than the Type 26 it will obviously be expected to be less capable than the Type 26.

But cost savings could also be made by adopting the Type 26 Lite. That is a Type 26 with some equipments left out, but leaving enough to match the capability of the smaller Type31 and being much cheaper than a standard T26.

Indeed it is quite possible that the larger Type 26 Lite could cost less than the smaller Type 31.

Items which could be left out of the T26 in order to bring the costs down are:- Type 2087 Towed Sonar Array, the 3 x 8 cell Mk42 VLS, the 2 x Phalanx CIWS, the Merlin Helicopter and the two Rolls Royce MT30 gas turbines. The maximum speed would be that obtained from Diesel Electric propulsion alone, probably a bit faster than the offshore Patrol Vessels. I assumed the Type 31 would be no faster. Removing these items will result in the Lite version being much cheaper than a standard T26.

Items which would be left in the T26Lite are:- the Type 997 Artisan Radar, Scot-5 Satcoms, EW systems and Decoys, eight x 6cell Seaceptor VLS, 1 x BAE 5inch Mk45 gun, 2 x DS30Mk2 30mm guns, Miniguns and GPMGs, a Wildcat helicopter, Sea Venom air to surface missiles, the Type 2050 Bow Sonar, and Stingray torpedoes launched from either STWS or MTLS or by the Wildcat helicopter using a Match type system. So defence against surface threats would be met by the SeaVenom missile armed Wildcat, and the 5” and 30mm guns. Defence against air threats would be met by Seaceptor missiles, 30mm guns and soft kill decoys. Defence against underwater threats would be by Stingray torpedoes launched from STWS (or MTLS) or the Wildcat. This would give a satisfactory weapon and sensor outfit for a ‘flexible general purpose frigate’, (a latter day Leander, but much more effective.) I doubt if the Type 31 would have any more, and I doubt if the Naval Staff would want any less.

If the costs of the Type 26 Lite are less than the Type 31 this would do no harm to foreign sales, particularly as the RN would be seen to be operating the Type 26 Lite which could well be a more imposing vessel than the Type 31.

The Type 26 Lite should be provided with “For But Not With” (FBNW) facilities on build, for all the equipments omitted. That is deck seatings, power supplies, wiring and cabling up to the appropriate compartment JBs, etc. so that the equipments could be installed readily at a future date if required. In the meanwhile the trim of the Type 26 Lite would be maintained by fitting ballast in the form of mild steel slabs designed to fit on the FBNW seatings.

Now let’s consider the costs under the following headings.

A. Concept Studies would have to include both the T31 and the Type26 Lite in order to satisfy the politicians that all options had been considered. A DRAW

B. Design Costs. For the Type 31 a full ship design would be required. An expensive undertaking. For the Type 26 Lite most of the design has already been done. All that would be required are calculations and drawings for the ballasting to allow for the equipments omitted. TYPE 26 LITE WINS HANDS DOWN.

C. The Shipyard Setting Up Costs. These one off costs would be required for the Type 31, but have already been met for the Type26 and hence the Type26 Lite. TYPE 26 Llte Wins.

If T26 and T31e are built in parallel, doesn’t that skupper the future “drum beat” of future ships? #UKShipbuildingStrategy

Yes, intentionally.

A stretched out drumbeat increases wage costs, as wages are typically a function of time and not product.

SJP has been given a target by a bunch of people a short distance away from me. That target is BAES.

In essence he is saying BAES get the T26 to get their house in order. After that everything is up for grabs.

What he doesn’t explain is where the food for all these other entities comes from. There is a deafening silence wrt any more money. Nor is there a steer as to where the magical export orders that are assumed to sustain the enterprise are likely to materialise from.

Game of chicken reaching its climax. BAE now have two cards – one is to blitz T26 to get it on contract and try to demonstrate they can hold costs in the hope of staving off full implementation in the actual NSS (this is just an independent study all of a sudden) to be published in Spring.

Or they can announce immediate closure of the Clyde………and call NCHQ bluff.

@NAB

thanks for the update [haven’t got a clue what a couple of the acronyms stand for though ;) ]

When i read Sir John Parker’s report, this morning, I thought of you for the ‘critical friend’ role [what we would call it in my industry anyway] or as Sir John recommends ‘an external technical consultant should provide constructive challenge’ [Recommendations for Governance No. 8, pg 2, Covering letter to Ministers]

… you’d be perfect.

good to know you are still lurking…

The other way to look at it is that BAES doing T26, and T31e being “up for grabs” allows T26 to be the last thing built on the Clyde (in a nicely delayed sense)… or if things go smoothly, not.

What I don’t really understand is the apparent focus on T31e. Do we have a queue of customers for a British built ship or something?

Type 31e? What is the lower case “e” for? If someone suggests “export” I may very well top myself.

Edit:

Oh bugger! See his letter to Ministers for what the “e” stands for:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-national-shipbuilding-strategy-an-independent-report

Largest concern is the shift from “National Shipbuilding Strategy” to “UK National Shipbuilding Strategy: an independent report”.

@ Ben of Hayling

I like the lite !

The classic fitted for but not with.

No need for a complete new design (BAES have spent £100m’s designing ( not detailing even! ) the T26 ) , just leave out the very expensive extras but provide the services and leave the allocated space in place unused till budgets allow or the T26 Full has an upgrade and the ‘obsolete’ kit can be crossed over to the Lite.

The BAES yards will need no new jigs , cnc programming etc and based on previous commentators posts once the first few ships have been built the build time (= money!) drops drastically which = more savings!

Given, the huge trade gap & the weakness of the Pound ( due to over low interest rates), should we aim to make the T31 as British as possible? So, 114mm gun, 12 of the deck launch Sea Venom (that are under development now), SeaCeptor, Stingray or Spearfish torps, Wildcat helo.

Might sacrifice a few unlikely exports, but save some foreign reserve cash.

Sir John clearly wants T31 to be the BMT Venator, built mostly in England by an alliance of Camell Laird and Babcock. While up on the Clyde BAES are told to focus on getting T26 right. Whether the MoD will have the balls to go for this plan and risk the wrath of Nicola Sturgeon remains to be seen. It also raises the question what all the yards will work on in the 2030s once both classes are done. New Air Warfare Destroyers? Or new Amphibs? Or just more of T26 and T31 to build up fleet? Big questions.

I’m not sure it’s Sir John who has placed his faith in CL and Babcock. There are other forces in play who would rather have a proctological examination with a red-hot poker than give anything else to BAES. Whether these people are correct – or even well-informed – is another matter entirely.

No-one in their right mind is going to buy a new 4.5″ gunned ship. Ammunition supply is a major issue, let alone capability.

@NaB

What are your feelings on a block build approach for GPFF involving the non-BAES yards?

How does that compare to a single yard/location “frigate factory” (or similar) approach?

It’s nonsense. It has been jacked up because certain people in NCHQ think they can pressure/punish BAES by this mechanism. Unfortunately, those people in NCHQ have never built a ship in their lives.

What worked for QEC, where you had to do distributed build to meet the timeline and because it could not be built in a oner anywhere in the UK, does not translate into it being a sensible thing to do for a much smaller ship. Particularly when the much smaller ship does not have the programme budget to accommodate all the unit inspections, sign-offs, transport costs and increased outfitting costs that you’ll get by shipping it’s constituent units around the country.

I suspect Sir John knows this – and to be fair to him he gives the MoD (and HMT) a proper kicking when he reviews governance and finance of RN shipbuilding projects. It is also absolutely correct to highlight that BAES have fallen into a mindset where they are reasonably sure they aren’t going to win lots of export work and so concentrate on paying their bills via the MoD – because they have a requirement placed on them (by MoD) to provide a domestic complex warship building capability, so base their plans solely on that and charge accordingly. If the NSS alters BAES corporate behaviour, then fair play – but I’m sceptical about the chances of success.

What is indisputable is that there was little or no call for more money which is the root problem in terms of both shipbuilding, but more importantly RN crew numbers. What that means is that you’re gambling on a short-term period where the limited amount of money available has to support more facilities, in the hope that significant export orders turn up to save the day, before the money runs out. Not holding my breath personally.

Where it was disappointing was that it did not call for all UK government-owned and operated ships to be built in the UK. That’s not a huge number of ships (or associated budget), but might have made more of a difference. But then I understand his remit was constrained to warship building by those whose idea it was in the first place…..

Really interesting! Thank you very much for the insights :)

May be a daft thought but has anyone considered that type 31 ought perhaps to be be built using some sort of private finance initiative where the shipbuilder pays for them and leases them to the navy for say 15 years including all maintenance costs (exept weapons systems).At the end of the lease period the navy could have the option of buying them outright for market price or they could be sold on to other countries.I seem to remember that a similar scheme was used to finance HMS echo & enterprise.This might be attractive to the government given how cash strapped HMG currently is. This would require them to be built by a group or consortium that would be able to maintain as well as build them

If I were BAES and we’re given the “opportunity” to build T26 whilst T31 deliberately went elsewhere I’d milk the MoD for all they were worth because I’d know that at the end there was nothing left for me.

Such is the power of a monopoly.

“…it did not call for all UK government-owned and operated ships to be built in the UK”. Sensible idea. Interesting documentary on the BEEB last night about shipbuilding and its collapse after the post-war boom.

The biggest unanswered question about a “2 Yards concurrent build” approach is what work there will be for both yards afterwards?

The report calls for a 30 year planning horizon but doesn’t propose what work goes in the back 2/3 of that time frame. One yard could possibly be given replacement Amphibs. The other a new class of AWD. But where does that leave our “world beating” T45?

I’m on record as calling for a “scrap and build” approach. The short successful life of HMS Ocean is a good example of this. Maybe this will come to pass for combat ships too. But only if HMG can stomach the upfront cost and governance requirements.

If I were bae systems I would just put the ship building division up for sale and if no one wants it shut it dwn.

On a side note I chuckled at mr fallons latest comments that US company’s need to give better offset deals to U.K. Company’s for contracts. Perhaps should of though of that prior to falling over themselves like a deck of cards to order P8, apache and protector for next to no return

PE,

That was my immediate question (last week) as soon as I read the suggestion: T26 and T31 in parallel skuppers the “drum beat” idea… although, as you point out, there are more than just FF/DD.

We are an island nation and are reliant on the sea for trade. By sticking two fingers up at the EU we’re probably more reliant on the sea for trade. NaB has a very valid point in bringing the “other ships” into the NSS equation too.

Developing the “game of chicken” theme it is worth asking, in the event of insolvency, who actually owns what?

Who owns the freehold to the Clyde Yards? Are they actually Royal Dockyards?

And who currently owns the IP to the T26 Design?

In other words if BAES were to put their shipbuilding arm into administration could HMG simply pre – pack the necessary assets into a phoenix company rather like Byers did to Railtrack…?

We maybe an island nation however almost 50% of trade by value arrives by air!

PE,

The government have the power to nationalise BAES so can’t see the point in faffing around with the alternative.

Mark,

By value maybe. Microchips, safron and gold though, are not actually important to our survival… Unless the microchips are the ones’ you put in the microwave and the safron is part of a curry ;-)

When oil, beef and 6″ shells start turning up 50% by air you’ll have me. Until then “value” means nothing :-)

Simon

Not all nationalisations are the same. It turns on the question of compensation to shareholders. Which is why I posed the question of who actually owns the key assets. No point nationalising a trading entity with no value in it if you already have tenure over what you need to start over.

Peter

Sorry, you’re right, I got way ahead of myself. When I suggested nationalisation I’d already assumed that the nation had been shafted by a monopoly and the state was simply seizing their assets and not paying any compensation to shareholders.

For the record, I don’t agree with nationalisation. I just disagree more with PLC monopolies on fundamentals (e.g. national security).

Elephant in the room is RN is not large enough to sustain ship building and no one wants to buy what we design. There’s no real requirement to increase the number of ships in the RN so the merry go round continues till someone grows a set and make a painful decision.

Perishables (food and medicines) are two of the largest uses of air cargo particularly from the US and Asia.

@ Mark

Trade by value :) Even the food you talk about is luxury stuff. Imported staples come in on container ships and if you can fly in enough gas and oil to keep the lights on then good luck. Sitting typing this a few thousand miles away from the UK conducting some contingency planning with the US, trust me keeping SLOCS open is a serious focus at higher levels.

As for the RN not needing more hulls or being big enough to sustain ship building. You can always use more hulls and we are stretched but just about coping. The decision to retain the ability to design and build complex warships is a government one.

There are no Royal Dockyards any more. In any case, the Clyde yards have never been dockyards and only under public ownership when British Shipbuilders was created. When that was dissolved in the 80s, the land ownership went to the new companies – in the case of the Clyde Yarrow Shipbuilders Ltd and Kvaerner Govan. So I’d have a very strong bet, the freehold is owned by BAES.

The IP for the T26 will have been done under Defcon705 at least, which means the Crown has full user rights. Access to the info will not be a problem. Finding someone to build it, would be.

There are plenty of requirements for more RN ships (as acknowledged in SDSR15 and other policy prior to that), just as there is plenty of requirement for a bigger FAA, leading to a bigger RN and even – God forbid – a bigger RAF. Trouble is there is no political will to pay for it. Two very different things.

Memory says that one of the Clyde yards is on land partly/mostly/all leased from Peel, don’t quote me on that though.

@Simon “the state was simply seizing their assets and not paying any compensation to shareholders”

That’s the kind of thing that happens in Venezuela and Argentina. It’s generally regarded as a Bad Thing – security of ownership is key to a functional economy.

I think the long-term aim should be to do something along the lines of what was mooted for Dover a few years ago before it got watered down. It’s all about getting all parties to pull in the same direction, and putting investment where it can be matched by financial capability. The key is to separate assets from the operating company.

Put the land in long-term ownership of government, whether that’s the Crown Estates or a pension fund, or Holyrood equivalents. I suspect there’s a deal to be done offsetting the value of the assets versus taking back on some of the pension liabilities to mean little cash has to change hands. The landowners then lease the facilities to an operating company for 10% of turnover, giving the landowner an incentive to invest in their assets to support the business. Operating company is a cooperative/owned by an employee trust or similar, which encourages a holistic view when setting wages etc, and means money stays in the system and doesn’t leak out to external shareholders.

Having been initially quiet enthusiastic about a Type 31 based on the BMT Venator design I began to have some doubts not least as to how you could pack all that capability into a 110 metre, <4000 ton hull, especially when compared in size to a Type 23;

Venator 110: Length: 117 meters Beam: 18.0 meters Draft: 4.3 meters Tons: 4,000 tons

Type 23: Length: 133 meters Beam: 16.1 meters Draft: 7.3 meters Tons: 4,900 tons

Interestingly and by comparison the Batch 3 Type 22 was 5,300 tons and 148.1 meters long, a Type 21 3,360 tons and 117 meters long, and a Leander weighed in at 2,962 tons and was 113.4 meters in length.

Given that the Venator design is said to be able to offer a Merlin sized flight deck with a 2 x Wildcat hanger, a 5 inch gun, a 24 Cell VLS and a mission bay able to resource 3 x RHIBS, it all seems to be a bit implausible that you could squeeze that amount of capability into a vessel quiet a bit smaller than a Type 23. With innovative design and modern build techniques it appears however it can be done but at the expense of what? Take the Singapore Navy's Formidable class frigate, in all but draft smaller than a Venator 110;

Formidable Class: 3,200 tons Length: 114.8 meters Beam: 16.3 meters Draft: 6.0 meters

Like the proposed Venator 110 design the Formidable's lack gas turbines relying on 4 x MTU CODAD diesel electric generators each producing 9,100 kilowatts and which still achieve a respectable 27 knots, but they do manage a towed array sonar, 2 x triple ASW torpedo tubes, 8 Harpoon and a 32 Cell Sylver A50 VLS. Only the gun is a bit light, a 76mm Oto Melara Super Rapid as opposed to the 127mm proposed for the Venator 110, however if we ended up with eight similar vessels as the Type 31 to back up the eight Type 26 it might not be that bad a result and with export potential to boot?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Formidable-class_frigate

You can have a lot of kit and systems in a small hull. What you lose out on is range and endurance. Questions to ask with all the T31 designs will be around Bunkerage, Magazines and Stores.

its been leaked that a type 31 has been provisionally priced at around 250 million!(even though its not designed yet! thats no going to increase fleet size as fast as some would hopet

I don’t see many River Class patrol vessels flying off the shelves to other Navies so I don’t see how using an existing design and stretching them by 20/30 metres is going to suddenly make them attractive and in demand for exporting in future.

We need to create a new ship (E.g. BMT’s Venator design) for the Type 31 from scratch which is attractive for export use, stealthy, will be built quickly under distributed ‘block construction’ methods in multiple shipyards and which will in turn create jobs throughout the country. We would then use this new Type 31 vessel as a marketing tool to showcase the ship and it’s weapons (E.g. CAMM, Brimstone Sea Spear, Spear 3 etc.) for export globally. Ideally we need to build 8 to 12 of these new Type 31 ships for the Royal Navy.

We, as a nation, cannot afford to buy ships from one supplier who writes out blank cheques to themselves to the tune of £1 Billion a warship.

Not many navies will buy the 150m long Type 26 from us nor will they have the cash to spend £1 Billion on it either.

We need competition to drive down costs, increase innovation and create jobs throughout the country.

We urgently need more ships.

Building a new vessel is a fantastic opportunity to create jobs, increase exports, create new and support existing supply chains and help our industries.

Buying ships only from BAE at £1 Billion each and having them made in only one ship yard is not the solution and this is clearly not working.

We should also scrap our Type 23 ships in the UK and recycle the steel so it can be used in future ships. This would create further jobs, savings and help protect industries.

Where have we heard £250M before?

http://www.naval-technology.com/projects/global-combat-ship-gcs-programme/

Oh how we laughed

Actually, the River-class (or, more accurately, the design family) is one of the most successful warship exports from the UK in recent decades.

Including the Amazonas, Rivers, Clydes, Krabi’s, and Al-Shamikh’s et al, there’s 17 built or building, 3-4 second-hand sales on the cards, and 15 prospects of differing likelihoods.

Not bad going for one of VT’s last hurrahs.

yet…

https://www.shephardmedia.com/news/imps-news/australia-issues-opv-rft/

How is it possible then that the River class OPV is not even short listed for this competition. Given that BAE Systems Australia is ‘a subsidiary of BAE Systems plc, [and] is one of the largest defence contractors in Australia’ you might have thought they would have taken the ‘off the shelf’ design of its UK sister company and, voila, for very little effort, offered the River class as the answer …

That it is not short listed could be for a multitude of reasons, I dont even know if BAE offered the River class [if not why not?], if they did, what made the Australian MOD decide not to short list it…

I understand TOBA, it is an uncomfortable business reality of a shrinking demand for naval ships in the UK, but the idea that BAE will compete for exports with the type 26/31 is a delusion if they cant even get shortlisted for the above…

oh , the mess …

ps

SEA 1180 is a bit of a special case, closer to the UK’s old MHPC program: Of which the new Rivers will be fulfilling the “PC” component and the Tupperware Life Extension the “M” bit, leaving the “H” part unanswered for now.

The RAN are (have been?) working with the MOD/RN on their approaches to the issues, however the two navy’s are on completely different life-cycles for the vessels in question now.

SEA 1180’s main purpose is replacing several classes of more numerous vessels with a single class of fewer vessels without losing capability.

Their approach is to go modular, as per what the Søværnet did with the StanFlex 300 to achieve the same result, on a hull form compatible with Hydrography and MCM.

The River-class either isn’t compatible with these modifications or the cost of modifications is comparable or in excess to a bespoke class.

@NAB

Given T26 and T31 “mission bays” – is there a standard for plugging equipment into the bay for water / power / data / HVAC or similar?

If not, how are those services to be delivered to a module or ISO Container, presuming equipment is not self-contained? Are there existing outlets near tie-down points or underfloor/overhead containment throughout for running services from shipboard risers or the like?

Trying to get a concept for the bays operation. Not expecting anything as formalised as StanFlex 300, but would be happy to be pleasantly surprised!

So Type 26 Lite? will be big and expensive, the Type 31 needs a new approach to getting a hull that can be capable, expandable in capability for the future and doesn’t cost the earth. The cost escalation for the T26 is just an example of something that started as a replacement for a T23 and is now as big as the T45! go figure! The strategy has to be exportable and cost effective otherwise it wont go anywhere in UK Government or overseas for that matter. There is also a load of talk around the design, so whose can we use? RR? BMT? or how about a proven international design that is then built here? I think that there are other designs here in the UK that haven’t been promoted everywhere as much as BMT’s so don’t get talked about. I think that if we leave the RN to dictate the design it will be a large and expensive ship, should be driven by exports and then adapted for the UK, NSBS alludes to this approach, anything else will just end up delayed, expensive and never used anywhere else….. oh that’s the Type 26 again!

Here’s a new design proposal from Steller Systems called Project Spartan as reported by Save The Royal Navy.Org:

http://www.savetheroyalnavy.org/steller-systems-offers-another-option-for-the-type-31-frigate-design/

I’m looking forward to seeing more detailed specifications for the Project Spartan and it adds another credible and promising option for the Type 31.

Movement on Type 31, DefenseNews by Andrew Chuter – £250 million per ship, if you pay peanuts you get monkeys ?

some quotes

Shipbuilding bosses and other executives have been invited to a central London meeting for Sept. 7 to be briefed on the broad outline of the Type 31 light frigate program by ministers as well as officials with the Navy and the Ministry of Defence’s Defence Equipment and Support agency,

Details of the program are sparse; but after nearly two years of concept work, the MoD appears to have finally cranked up progress with three separate events within 20 days aimed at laying out the plan to acquire the warships.

The Defence Contracts Bulletin notice said the Sept. 7 announcement will be an industry briefing covering details of the program, including the pre-procurement and procurement phases. This will be followed with the MoD’s ship acquisition team outlining further program details and holding discussions with industry at the upcoming DSEI exhibition in London in mid-September and industry day briefings on Sept. 27 and 28.

The program official said the unit cost that the MoD was working toward for the Type 31 frigates was closer to £250 million than the £330 million reported by the media.

The prospect of a cheap and cheerful frigate has raised concerns among analyst’s that the warships will only be suitable for constabulary duties like anti-smuggling and piracy prevention rather than front-line war fighting.

http://www.defensenews.com/naval/2017/08/25/uk-deadline-for-type-31-frigates-just-not-going-to-happen/

Well if the 250 mil price doesn’t include all the high ticket price items being transferred over from Type 23s as they retire…

Babcock’s Arrowhead 120:

https://www.babcockinternational.com/Case-Studies/Arrowhead

Brochure and video links toward the bottom.