The Multi Role Vehicle (Protected), or MRV-P, is a British Army programme that will replace a number of light armoured and utility vehicles

Share on twitter Twitter Share on facebook Facebook Share on linkedin LinkedIn Share on reddit Reddit Share on print PrintThe Multi Role Vehicle – Protected (MRV-P) is a large project to bring into service two protected wheeled vehicles to replace many; to bring commonality to the fleet and reduce the logistics footprint for utility vehicles. It is fair to say, the programme has been struggling to come to fruition and was intended to be in service by last year but as of early March 2021, no orders have been placed. MRV-P is to be obtained in two packages, with the current preferred options being the Oshkosh Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) for the smaller variant (package 1), and either the General Dynamics Eagle or Thales Bushmaster (Package 2) for the larger variant.

The history and candidate vehicles are described in a previous long read (click here) but in this article, I will propose we take (yet) another pause on MRV-P and look again. Whilst all three are fine vehicles, two of them are nearly two decades old and none have any significant UK content. It is unlikely that whatever comes after Challenger 2 will be British, if the news reports are true, Warrior will be cancelled; and whilst Ajax and Boxer will have UK content, neither is fully sovereign. MAN SV and Oshkosh trucks are not British either, leaving just FV430, Foxhound, Terrier, Land Rover, and the Jackal/Coyote family as the only vehicles with British heritage.

Does this matter, I wouldn’t be writing this article if I thought not?

The Royal Air Force and Royal Navy have coherent equipment strategies strongly anchored in British research, design, and manufacturing; Team Complex Weapons, Team Tempest, and the National Shipbuilding Strategy. This provides some element of insulation from budgetary predation. In my recent article on the Integrated Review I wrote the following about establishing a Land Equipment Industrial Strategy;

If COVID has taught us anything it has taught us the value of onshore research and manufacturing capacity. Again, much of this might not be wholly in the gift of the Army but it should implement a Land Equipment Industrial Strategy that recognises the value of onshore research, design, and manufacturing. This might include portfolio or category approaches like the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force do with their complex weapons. These portfolios might include utility vehicles, weapons, sensors, computing or infantry equipment, or anything else. One of the reasons for the comparative success of the MBDA led complex weapons portfolio is an assured pipeline and long-term view, see my point on stability above. Does this mean I am proposing the UK go its own way on everything, of course not, it simply a suggestion that the British Army needs to anchor its equipment plan on British industry as much as it can. It should absolutely recognise the value of having equipment that exists within a large international user base but balance this with a sensible industrial strategy.

The UK aerospace industry has a turnover of £35billion, the shipping industry; £3billion, both lobby for the RAF and RN, respectively. The hugely innovative UK automotive industry has a turnover more than double that combined but is hardly troubled by the British Army, which needs to find again its industrial roots to exploit this embarrassment of riches it, for whatever reasons, has been recently unable to.

A Guiding Light from the Integrated Operating Concept.

The introduction document to the Integrated Operating Concept provides some cues for MRV-P;

- Have smaller and faster capabilities to avoid detection

- Trade reduced physical protection for increased mobility

- Rely more heavily on low-observable and stealth technologies

- Depend increasingly on electronic warfare and passive deception measures to gain and maintain the information advantage

- Include a mix of crewed, uncrewed and autonomous platforms

- Be integrated into ever more sophisticated networks of systems through a combat cloud that makes the best use of data

- Have an open systems architecture that enables the rapid incorporation of new capability

- Be markedly less dependent on fossil fuels

- Employ non-line-of-sight fires to exploit the advantages we gain from an information advantage

- Emphasise the non-lethal disabling of enemy capabilities, thereby increasing the range of political and strategic options

Not all of these are relevant to MRV-P but clearly, some are, and whilst the IOpC is still relatively new, any new programme cannot afford to ignore these obvious signposts, especially that of fossil fuel dependence.

Levelling Up and the UK Prosperity Agenda

Levelling Up is a whole of the government initiative to improve the economic fortunes and wellbeing of all parts of the UK, especially the English Regions and devolved nations. Like many such initiatives it can mean different things to different people but there is no doubt about the seriousness which this government places on it, and the financial backing it is providing.

The Government has also committed to double research and development investment with a target of spending 2.4% of GDP on public and private R&D by 2027. Some of this R&D will go towards contributing to the now legally enshrined ‘Net-Zero by 2050’ objective. Government-supported initiatives include the National Productivity Investment Fund, Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund and the Strength in Places Fund. A recent example is the £80 million UK Automotive Battery Industrialisation Centre in Coventry, as part of the wider Faraday Battery Challenge. A recent defence oriented example of research funding is the Thundercat programme for the British Army’s light cavalry. This was a collaboration between the Armour Trials and Development Unit (ATDU), the Light Dragoons and a number of industry partners, funded by the UK Research Institute CLF Innovation Fund. Industry partners included Thales, Safran, Vitavox, Intracom, Spectra Group, Supacat, Drone Evolution and others.

Towards a Land Equipment Industrial Strategy

This article is not about a Land Equipment Strategy specifically, but a recast MRV-P programme could be a key part of it, providing benefits to both defence and UK research and industry. If those technology areas align with the Integrated Operating Concept then the synergies become self-evident.

Forming an equivalent to Team Complex Weapons or Team Tempest for land equipment would provide a range of operational benefits and provide the industry with a predictable pipeline of business on which they could base capital and human resource investments such as apprentice schemes, robotic manufacturing equipment and test facilities. Commonality across multiple vehicle families, modularity where it makes sense and a flexible production facility would all be key features of ‘Team Land’. Whether a national champion or more loose amalgamation of industry and academia is beyond the scope of this article but there are plenty of organisations that could play a meaningful part.

The industry is not a charity; without a design contract or a winnable competition, there will be no design effort in the industry. If we look back at the British Army’s vehicles of late, all of them bar Terrier and Foxhound have been adaptations of previous designs. Design authority should therefore rest with the MoD, forming a core design team inside the MoD, almost a return to the Establishments.

Although mention of the Establishments was somewhat tongue in cheek, one aspect of their design approach does need to be central to this proposal, ‘systems thinking’. One example I always come back to when describing this is the Antar tank transporter had the same engine as the tanks it was designed to transport. Casting this concept forward means the MRV vehicles family would all use common engines and drive systems, air filtration systems, instrumentation and controls, suspension, steering, wheels and tyres. This is about more than administrative neatness, commonality provides benefits in maintenance training, spares inventory, diagnostic aids, even maintainer currency. Many of those common subsystems are made right here in the UK and so is the design and integration expertise, just take a look at some of the links below;

And this is by no means an exhaustive list.

To be realistic, if the future of British Army armoured vehicles is onshore integration and selective manufacture of other nation’s designs, protected vehicles should eschew this trend and aim for something wholly sovereign.

Finding a Headline Concept for Multi-Role Vehicle

The capstone for this new vision of light to medium protected vehicles should be aligned with the Integrated Operating Concept and national objectives, and for me at least, this means…

Be markedly less dependent on fossil fuels

The MoD has funded research into hybrid vehicles for at least two decades.

TRACER was equipped with a hybrid electric drive system, FRES Chassis Concept Technology Demonstration Programme with both AHED and SEP had elements of hybrid electric technology, QinetiQ HED likewise, and the £63million Protected Mobility Engineering & Technical Support (PMETS) contract will demonstrate the latest hybrid technology on a Foxhound and Jackal.

The three videos below each have UK engineering content and UK taxpayer money in them.

Magtec and SEP

Supacat, NP Aerospace and Magtec

QinetiQ and Multidrive

Multi-Role Vehicle (Protected) must include this technology as a fundamental design choice.

Vehicle Requirements

The original strapline for MRV-P was ‘medium protection and medium mobility’ and I think this still stands. There also seems to be a growing realisation that Boxer and Ajax are not medium and what might be more applicable to many situations is a lighter family of protected vehicles, but not just utility vehicles. I would tend to leave Foxhound and Mastiff out of this as they represent specialised light and heavily protected vehicles for use in specific scenarios.

MRV-P would therefore replace Jackal/Coyote, some Land Rover and Pinzgauer variants, Fuchs, Panther and Husky. It would also be an opportunity to develop Light Cavalry vehicles within MRV-P. Light Cavalry of late has tended to be equipped with what is available, RWMIK and Jackal/Coyote, not as part of systematic evaluation of need. We should also consider the Oshkosh MTVR articulated tractor units as part of the revised MRV-P programme.

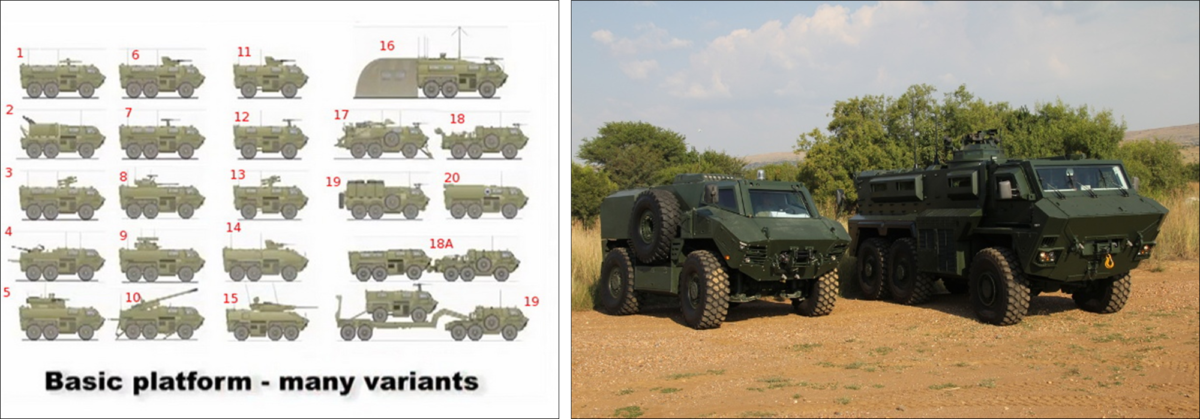

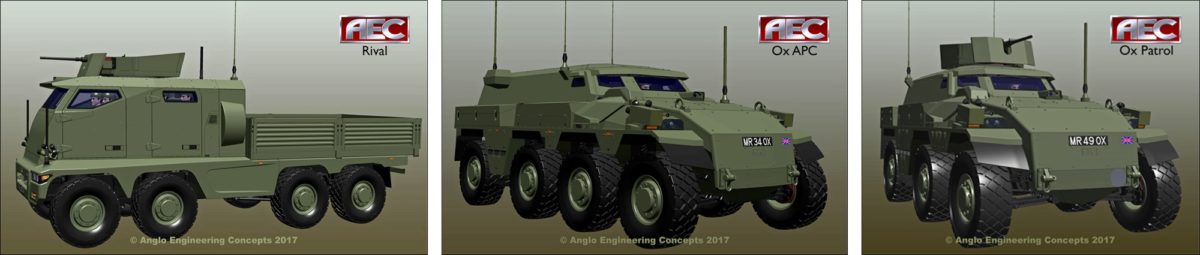

A few examples of this kind of ‘systems thinking’ spring to mind; the BAE RG-35 (now Nimr JAIS) and Anglo Engineering Concepts vehicle designs. There is an older article on Think Defence extolling the virtues of the RG-35, and another from the same author but using the Supacat HMT at UK Landpower. All three promote the value of commonality across a number of variants and drivelines, the key being system commonality, not necessarily vehicle commonality.

The former was developed to serve others and the latter, still at the design stage only. Am not suggesting we go all in either, but the concept and thinking of both these examples do provide a useful roadmap and in the case of Anglo Engineering, a well-thought-through series of vehicle designs that maximise commonality, they absolutely deserve more consideration.

ONE – Fast Scout and Liaison

To replace land Rover WMIK, Jackal and Panther, a light armoured car, 4×4, equipped with a lightweight turret or RWS equipped with combinations of GPMG, HMG, GMG, ATGW or a lightweight medium calibre automatic cannon (20-30mm). With a crew of between 2 and 4 and a high degree of road mobility, AEC Raðe and Panhard Crab are examples of what it might look like.

With a maximum weight of 9 tonnes it would also be highly air portable, a single sling load by Chinook or three in an A400M for example. It would not be heavily armoured but by virtue of using a crew capsule, central driver position, low profile and fully enclosed against the environment and CBRN contaminants; improved survivability over open-topped vehicles like RWMIK and Jackal. At the upper end of this type of vehicle would be the Textron TAPV entering service with Canada, although recognising the very long lineage of this particular vehicle. The Otokar Akrep IIe is another design with a long history but one that is looking to the future with alternative propulsion. The Arquus Scarabee is one of the more recent realisations of the concept.

The rear-engine configuration allows the vehicle to have a low profile and central protected citadel whilst providing ease of access to the engine and associated electrical equipment. However, whilst ideal for cavalry and liaison roles, this rear-engine configuration produces a sub-optimal design for general utility, command and control and light logistics use.

TWO – Multi Role Utility

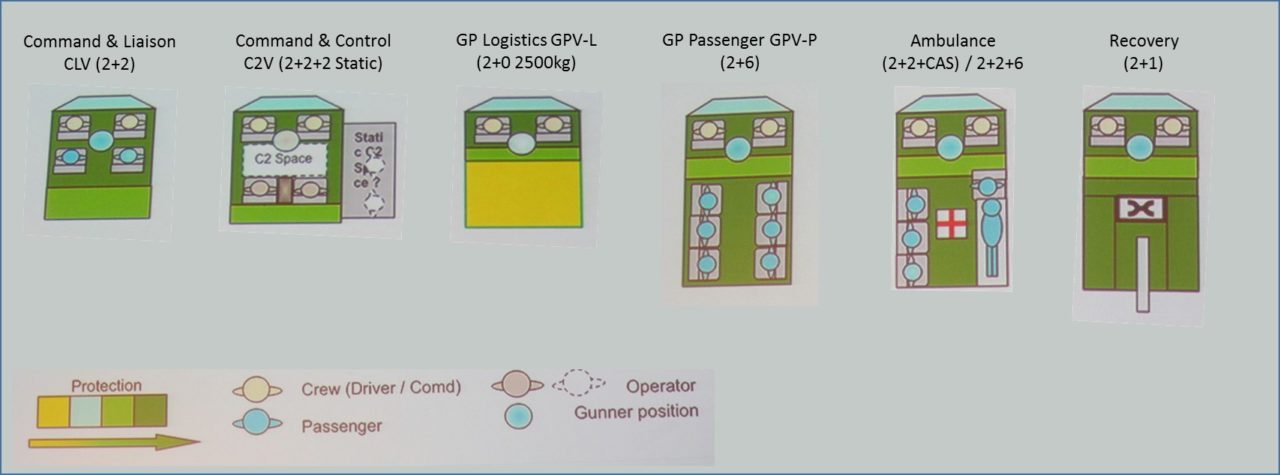

The second category of vehicle is where I depart from conventional wisdom as described in the image below, the notional requirement visualisation for the existing MRV-P requirement;

Design ONE would cover the far left role, and for the second (Command and Control), I think we cannot now accept the concept of a static lean-to shelter in an age of pervasive surveillance, more mobility and space is needed. For the logistics role, the ‘QM’s runaround’, again, I think we should go for more space.

There is also another argument for a larger vehicle.

By the time we have added driver vision aids, situational awareness cameras, ECM, communications equipment, modern diagnostics, GVA compliant displays and environmental protection equipment the cost to payload ratio becomes difficult to sustain for a 4×4 vehicle like JLTV (the current favourite for the left three in the diagram above. Increase the size to those on the right, generally, in a 6×6 configuration, the cost to payload ratio becomes much more favourable. It does this because the really expensive stuff is about the same cost for a 4×4 and it is for a 6×6. Where size is a factor, like with Foxhound and its demanding turning circle specification, this ratio can be carried. For something like JLTV, the payload can be increased with the use of a trailer but this reduces mobility significantly, so I come back to the question, what is the point of a 4×4 protected vehicle when a 6×6 offers so much more payload for a similar cost? Although the ‘air is free steel is cheap’ analogy might be stretching it somewhat for the land environment, it must have some relevance if air portability is not a significant concern?

It is clear that the current MRV-P is not intended to be a fighting vehicle but perhaps it should be, something better protected than envisaged and with applicability across a wider set of operational environments?

With this in mind, I propose that we develop a 6×6 or 8×8 vehicle based on a continuous V-shaped hull with maximum systems commonality with design ONE.

Old and new vehicle concepts are useful for inspiration; the AEC Ox, Protolab PMPV, Arquus/Nexter Griffon, Pandur Evo or Patria 6×6 for example. It would certainly be interesting to resurrect the Splitterskyddad Enhetsplattform (SEP), at least in its first 6×6 iteration with Magtec drive systems as in the video above, but that would be far too close to Boxer for comfort, and would inevitably lead to fewer Boxer. More realistic is something more akin to the 14 tonnes, 10-tonne payload amphibious Protolab PMPV MiSu. The vehicle configuration places the crew compartment behind the engine, similar to a modern-day Saracen, although it does have the unequal axle spacing of more modern truck-based vehicles. Speaking of Saracen, something visually similar (but very different in things that matter) can be found in the AEC Ox, in multiple axle configurations, but again, perhaps a bit too close visually to Boxer, however ridiculous that worry might be. The AEC Rival is more akin to a conventional truck layout.

The 6×6 Multidrive/QinetiQ Hybrid Electric Demonstrator (HED), based on a Multidrive chassis design, had all the electrical and power generation equipment in a central spine (or skid). These variations on engine placement would be examined as part of the design process and the outcome might depend on whether mechanical transmissions or hub motors are used. I don’t want to say we need a specific configuration or design, but there are plenty of options to consider and examples to draw upon.

What I am more bullish on is the usefulness of this type of vehicle alongside Boxer. Many of the module variants and roles being proposed for Boxer beyond the initial set could equally be delivered by this type of vehicle, reducing the demand for the very expensive (but very good) Boxer.

This would create a large volume at the rear of the vehicle that could be adapted for many different roles; basic logistics with a Marshal loadbed, with a HIAB jib, as a fuel or water tanker, anti-aircraft with systems from the Stormer based HVM, a recovery crane and winch, infantry carrier, ambulance, command and control, C-UAS or mortar carrier; the possibilities are endless.

THREE – Light Tractor

This is the final proposal, a variant of the Multi-Role Utility design that would ultimately replace the Oshkosh MTVR tanker tractors. Whilst these are excellent vehicles, they are not protected yet are obvious high profile targets. They are also unique in UK service and if we want to simplify we need to think about this kind of vehicle. Both AEC and the BAE proposed protected tractor units for trailers as part of their concept, adding a fifth wheel for a trailer unit.

Another possibility that would avoid the need for a fifth wheel (and therefore a dedicated variant) would be to implement a powered trailer. A good example of a powered trailer is the Multidrive flex frame that used an articulated and hydraulically actuated trailer with a power take-off propshaft to maintain powered contact with the ground over undulating terrain, with 50 degrees up/down and 50-degree side to side movement.

Instead of mechanical power for the trailer, using power generated by the tractor vehicle might enable the use of electric hub motors on the trailer, like this from Joskin

Summary

This proposal is rested on a number of points;

- Back British research and industry, and in doing so, contribute to the prosperity and levelling up agenda

- Pick a capstone concept aligned with the Integrated Operating Concept, in this case, the desire for significant fossil fuel reduction

- Be ruthless in our pursuit of commonality across the vehicle fleet, at least at the system and component layer

You will notice I have been somewhat light on specific design specifications, arguments about weights and measures, GPMG or 20mm cannons, or series or parallel hybrid; they are for another time.

I fully realise this is ‘fantasy fleets’ and requires much to happen that is not in the gift of the British Army.

With some vision, support and buy-in though, this fantasy can be realised.

See you in the comments…

Table of Contents

[adinserter block=”2″]

[adinserter block=”1″]

Change Status

| Change Date | Change Record |

| 15/03/2021 | Initial issue |

| 22/07/2021 | Format update |

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

As usual well thought out provoking article. I feel intially I want to talk about AVA, TMV, Chassis, nimr JAIS etc. But I think a strategy for viability needs addressing in the first place before we think fantasy vehicles. I think we need either to design something that is either:

1) exportable in good numbers to other militaries

2) Based on an existing commercial design

3) could result in a commercial design (thinking humvee)

4) uses commercial components

So if we’re to keep a 4×4 option something like a vehicle based on the new defender. Or maybe a JCB tractor. If completely new maybe looking at something conceptually something that can be turned into something like the next Jaguar F-Pace. 4×4 opens up to the civilian market.

The Defender has a pedigree in both military & all over the off-road world. The current version looks a bit soft for the extreme arena Dakar rally etc. Interestingly Tata motors & Indian firm have a defence arm which by the looks of it produces what looks like average at best military vehicles. Surely if they could utilise the defender name & engineering skills in the UK that could be a good avenue to explore.

Manufacturers like Honda & Toyota are built in the UK a spin-off brand looking at particularly the off-road market. May allow them to commercially distance themselves from warfighting

For a larger 6×6/8×8 why not look to utilise something from JCB ?

In terms of light tractor surely Leyland DAF is a good place to start?

Just my initial thoughts. But if we can something that adds to prosperity outside of the military then that will appeal to Government.

Final thoughts I believe there maybe some thoughts around new logistics considering we can’t afford Boxer for everything and logistics vehicles particularly in Strike will be in a potentially more vulnerable position I do think that there is maybe some merit in Rheinmetall revisiting the Wisent design/concept potentially built at Telford? The vehicle being modular available 6×6, 8×8,10×10 could suit Command on the move, Sky Sabre, GOAT Archer/AGM, MLRS other capabilities not able to be carried by MRVP2

Thanks again for writing the article

If the defense review will include a focus on domestic industrial strategy then JLTV looks set for the chop. The French scorpion program looks very promising it’s a pity we are 5 years behind them. I thought fox hound offered a good base to build off. Maybe it was too tall but I think it had potential. Whatever is selected I don’t think we have time to develop fresh from the drawing board.

reading this it makes a lot of sense, I think this will be a very important part of the army’s future with the governments desire for fwd engagement with allies a gd way to showing uk engineering talent also.

I would like to see us start by concentrating and developing the Jackie/foxhound teaming as an interim step and develop going fwd from there

As for designing our own.

That has its own challenges. Using anything COTS is almost a non starter.

Commercial vehicles are designed around vehicle and driving licence regulations. Cat B licence 3500kg Max as too are regulations for tachographs and specialist licensing. It does mean that the 3500kg vehicle already has limited payload and scope for conversion. Might as well start with a clean sheet.

Even the replacement for the GS Landrover is gong to have to be 4-5 tonnes GVW to be worth while.

Interesting article as always.

With the US having approved foreign military sale in 2017 we have precisely how may JLTV’s

Not saying it the best of most suitable but cost per unit will be almost unbeatable.

As we’re waiting, I’d just like to try and round out something that builds on the above and a thread by Jon Hawkes illustrating how Boxer modules encourage industry.

Could we compartmentalise a build into various modules?

Dictate a single chassis size that would be suitable for a lower 4×4, 6×6, or tracked module.

Illustrate the means by which the drive module would connect to the upper/s either as a physical strata or else a set of engineering specifications.

Companies could then independently develop in wheel drive modules in various configurations, others could develop power/driver modules, mission modules or combinations of these.

This would I hope occur via ‘the invisible hand’ with next to no input from government other than a guiding set of specifications and an underlying demand.

The various modules would obviously be interchangeable across all incarnations and allow specialised outfits (either independently or in cooperation) to have a bite at a project ordinarily beyond their scope.

End result might be something like an evolving RG35 family but constantly and independently competed.

I have given this all of an hours thought, it’s probably pretty bad.

Replying to Captain Nemo: I quite agree, define the parameters but let industry focus on the R&D to innovate within and around those. If you try and define the perfect detailed spec at the outset you stifle innovation and ideas and at best end up with what you asked for years ago but not what you need now. Worst case you realise this as the project develops and continue to try to update your specification adding cost and time to the project, sound familiar? Better to define the broad scope based around some fixed requirements and refine as industry solutions emerge or steer as strategic requirements emerge. imagine what Could have been if the Boxer module was designed with even greater consideration for the ‘universal mission module’ and could be carried on a wider range of platforms for a really tailored force. Those that have said Boxer is too expensive/over-protected a platform for an ambulance or artillery variant may be right or may be wrong, it surely depends on the context of the deployment. The off-Road demands of deploying in Africa or Middle East or Scandinavia are vastly different.

Wheeled vehicles i know less off however i can give a pointer on electric systems there is still a need to overcome the energy density problem, if they wish to enter the same domains as diesel powered vehicles

Pausing procurement now for another re think would only delay yet again the deployment of a more capable vehicle fleet.

However, I do have a kind of alternative that might help achieve some of the same benefits for industrial strengthening.

All of the new and existing vehicle fleets will need a lifetime of maintenance, overhauls, upgrades and enhancements. The government can establish a dedicated centre for each of these programmes. In the case of UK manufacturered vehicles this would logically be based around the production line, but for imported vehicles a whole new facility could be established, stragetically sited to act as a hub for suppliers and support services. Gradually grow the UK content over time, with all suppliers and contractors having to adopt a minimum standard for training, R&D, apprenticeships etc. This could be done with MAN or JLTV for example. Production and assembly are only part of the vehicles life cycle requirements. The real work and potential value is in keeping each vehicle going for 20+ years.

Approaching things in this way could expand the industries capacity to move back into development, and production in the future.

Each hub could also serve as a training centre for the British Army for that vehicle family and promote cross links between the army and industry in a way that is already much more common in the aviation sector. Does the REME need to be able to do a complete strip down and rebuild of a vehicle? Instead send it back to the factory or hub and concentrate on routine and front line maintenance.

Put a rail link into each hub and build up some rail freight capacity. Team each hub with a University and FE college too. Stick them in places with chronic unemployment problems to kick start the local economy.

There’s lots that can be done. For that matter, lots that USED to be done!

@James O: what about hydrogen powered vehicles. Currently there’s a lot of buzz around MHD with electric hub motors for heavyweight ground use and aviation. Could be useful to have air and ground vehicles on the same fuel?

i have long agreed with your views on commonality and think there is an opportunity here.

the army has nearly circa 8k man trucks, and circa. 10k land rovers, not to mention the mix of other vehicles. I think we could have a requirement for 1k vehicles per year indefinitely as part of a fleet management strategy and perhaps we should invest in supacat to produce a family of vehicles for us that we can potentially export.

boxer is great, but what’s to say we can’t make a British armoured cab vehicle that has interchangeable payloads that are unmanned, then boxer has manned modules and these assets have unmanned modules that are linked to a 4 person armoured cab. Perfect for MLRS, AAD, precision fires and other weapons systems that are essentially unmanned but controlled from the cab.

like boxer these could be modules, but far less expensive.

I think this has some merit and certainly 6×6 is probably the way to go for the majority of this requirement.

No mention of the MRV P in the review. Does that mean it’s not gong the happen.

Quickest way to do this would be to get the licence and IP from someone like Protolab PMPV 6×6 and use UK manufacturing to build.

I think it would doable as the Finns would like the price reduction gained from numbers and a larger user pool for spares and support and would be quite tempting for smaller armies.

I think we should rethink the MRVP requirement after the recent defence paper a nd we need to get a decent capability that can step and and step down as required.

The Royal Marines are returning to their commando roots and there is an opening for the army to supply the mass for an amphib capability more like the 3 Cdo Bde we are used to, so a swim capable cheapish 6×6 with a decent load capacity would help but also be more suitable for our expeditionary posture.

If we choose the 4×4 Bushmasteror Eagle (without getting the 4×4 version) we will have missed another opportunity imo.

Replying to Orlok, perhaps if the MOD had moved at speed, they could have purchased the “Honda” factory in Swindon. 5 miles of the M4, 3 junctions down to the A34 and Southampton, just down the road from Brize Norton, just up the road fro REME Trg Centre at MOD Lyneham, and 3 junctions down from MOD Abbeywood. You couldn’t have got a more suitably located site if you tried.

What about creating a truly modular vehicle system around the medium weight bracket?

If you could agree a minimum useful length say for a workstation or 2 protected seats rather than having 1 module say command/APC you could potentially have troop carrier & UAV control station in the same vehicle.

If you then had a 4×4, 6×6, 8×8 or 10×10 drive modules built to standardise lengths each vehicle could have an agreed number of modules e.g. 4×4 2 modules 6×6 3 modules, 8×8 4 modules 10×10 5 modules. Like Boxer in the main the strength would come from the drive unit unlike Boxer you’re are not stuck with only & 8×8 Chassis.

This would allow easy creation of a say 6 person APC or 10 person APC. Also potentially allow say a sub module contained an RWS & you wanted to upgrade it & associated computer terminal you could then get that company to create a new sub module with all the new systems & simply swap that sub module, equally all Comms could be in one module. Say then suddenly you wanted a 12×12 vehicle you could simply add the sub modules to cover the increased length. There’s no reason say that the vehicle was an artillery system & 8×8 that 2 modules be permanently joined so you could transfer artillery to either 6×6 or 10×10 then either add empty submodules or workstation or ammo containers etc.

Recently been looking at the Ranger armoured vehicle which looks extremely capable 28 hp per ton, STANAG level 4, Hybrid etc. looking how it’s built & the number of wheeled variants available how the protection is constructed no reason something like this couldn’t be added to that type of vehicle.

Probably overcomplicate just an idea

That was a really interesting article, a lot of detail and a lot to think about. I’d also be minded to add that there is lots of manufacturing potential in Northern Ireland and we should absolutely make the most of component manufacture where we have the specialisms to. It’s not sexy talking about parts supply but it’s just important as you say, common/standard components makes life so much easier for everyone.

FFS, how could things get worse?

Looking forward to your Ajax post mortem