A UK Hospital Ship has been a recurring theme in the media and over the years, accompanied by much online discussion, but it has never really gained much traction in the previous Government, despite the odd headline.

With a new Government, and one perhaps more aligned with overseas development and disaster response, climate change, and industrial strategy, perhaps it is time to turn over the stone and have another look? It is not unreasonable to envisage the motivation for a new Government looking again at hospital ships, and making better use of the UK’s significant Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) budget.

The Importance of Terminology

Although hospital ship is often used as a generic term and is arguably much easier to understand than Primary Casualty Receiving Facility (or ship), there is a massive difference.

We need to get this out of the way early.

Ships dedicated to providing medical support have a long history, but the term Hospital Ship was first defined in the Geneva Convention and Maritime Law (3rd Hague Convention) of 1899 and additionally in the Tenth Treaty of The Hague Convention of 1907.

The convention is very specific about restrictions, marking, and rules of use

Read it here

As an example, they must not be used for any other purposes, all belligerents have the right of search and must be painted white with a green band. After WWII, the Geneva Conventions of 1949 further enhanced and updated provisions for Hospital Ships, specifically Convention (II) for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea. Geneva, 12 August 1949, Chapter III.

Link here

The comprehensive 1949 Convention has also been subject to two sets of ‘commentary’, one in 1960 and the latest, in 2017, again, links above.

Needless to say, the legal definition of a hospital ship is a serious matter for anyone thinking they might want one.

Now if you read that and thought, bloody hell, that is a complex business, may I introduce you to the 280 pages of AJP-4.10 Allied Joint Doctrine for Medical Support

It is not possible to summarise such a comprehensive document easily, but of most relevance is the concept of different types of facility role, we often hear terms like Role 2 or Role 3 in relation to medical facilities.

A Role 3 Medical Treatment Facility is defined as;

A hospital response capability provides secondary health care at theatre level. A Role 3 MTF must provide all the capabilities of the Role 2E MTF and be able to conduct specialized surgery, care and additional services as dictated by mission and theatre requirements. In a Maritime context, Role 3 support is provided by the primary casualty receiving facility fitted to Royal Fleet Auxilliary Argus when it is designated as the primary casualty receiving ship.

RFA Argus is typically called a hospital ship, but she isn’t, instead, she is a primary Casualty Receiving Facility as defined by AJP 4.10 and UK-specific doctrine.

Painted grey, armed and able to conduct other nonmedical tasks, she is most definitely not a hospital ship, even though her primary role is medical in nature.

We might want a hospital ship, we might not, but we need to be clear on the difference.

UK Medical Terminology and Doctrine

The Allied Joint Doctrine for Medical Support describes how medical care is organised in a defence context. The linked document is nearly 200 hundred pages long, it is a complex subject that is beyond the scope of this article.

But there are a couple of key diagrams that illustrate key points.

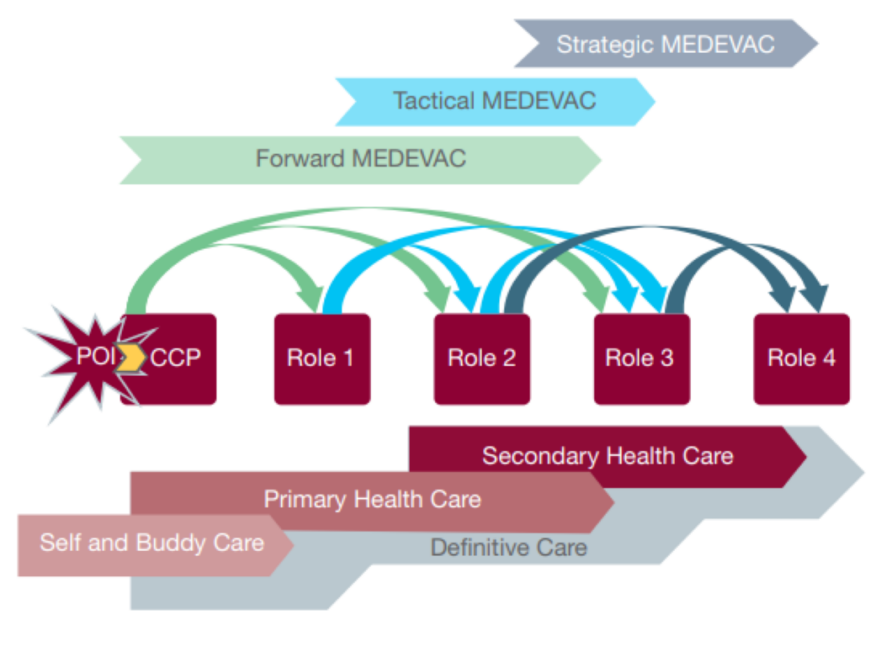

The first is the care continuum, illustrating how patients are moved through different facilities, or roles.

Role 3 is described as

Role 3 (R3). The role 3 of military health care comprises a set of deployable specialist- and hospital care capabilities which at least includes computed tomography (CT) and oxygen -production in addition to all the R2 capabilities listed above. R3 capabilities may reduce the need for a repatriation of patients and enable a higher standard of care prior to strategic evacuation.

UK 2.6. The UK defines Role 3 as a hospital response capability which provides secondary health care at theatre level. A Role 3 medical treatment facility (MTF) must provide all the capabilities of the Role 2E MTF and be able to conduct specialised surgery, care and additional services as dictated by mission and theatre requirements. UK

Role 3 MTF may provide CT, but does not have the means to independently produce oxygen and is reliant on cylinders and oxygen concentrators for supply

A Role 3 facility can look like that, below.

Or this.

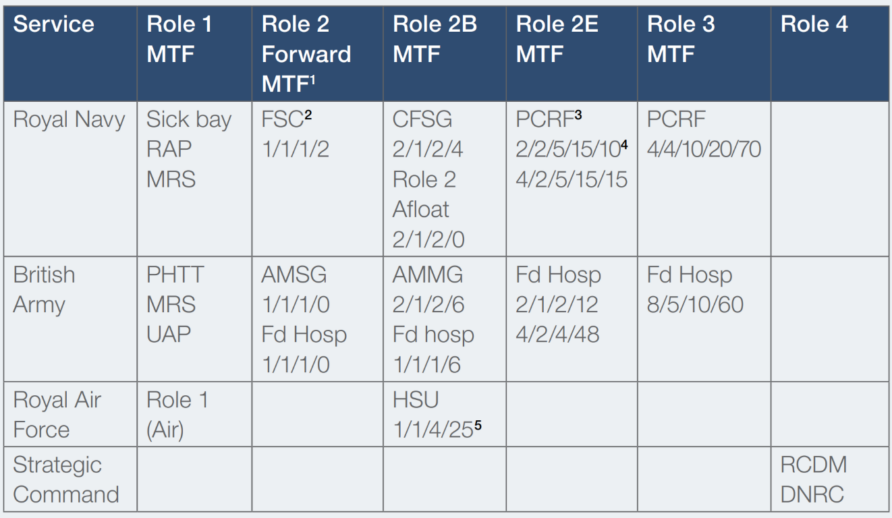

As can be seen from the table below, the Role 3 requirement for littoral operations is the Primary Casualty Receiving Facility.

The series of numbers under Roles 2 and 3 medical treatment facilities relates to the number of emergency department bays/surgical tables/intensive treatment unit beds/intermediate care ward beds within a facility.

This will inform any subsequent discussions on sizing.

Hospital Ships Around the World

Perhaps the most well-known hospital ship (from a UK perspective) was the SS Uganda and her service during the Falklands conflict. She was converted from an educational cruise liner into a three ward hospital ship in a very short period of time and served with distinction throughout.

The largest of the modern hospital ships is the US Mercy Class, USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort.

Both are converted San Clemente class tankers, displacing approximately 70,000 tonnes.

With a 1,000 bed capacity and 12 operating theatres, they are also equipped for the widest range of medical treatment options.

Mercy is home based on the Pacific coast and Comfort, on the Atlantic, the latter shown below during her deployment to Haiti following the earthquake in 2010.

Both are activated in response to need rather than being permanently in operation, and they have some design flaws that are often the subject of much discussion; lack of aviation facilities, poor patient movement routes, relatively low speed and their sheer size makes them unsuitable or overkill for many situations.

Despite these concerns, they are both unrivalled in their capabilities.

In 2023, the US also placed an order with Austal USA for design and build of three Expeditionary Medical Ships (EMS).

Russia and China also have hospital ships

The Russian Ob Class included four vessels, but only the Irtysh appears still in service, the Severomorsk and Enisey inactive at Severomorsk and Sevastopol.

China operates the 30,000 tonnes 400-bed Daishan Dao, alternatively known as the Peace Ark, designated Type 920 Class.

A second vessel of similar design (although larger) has been recently commissioned, called the Silkroad Ark.

In addition, there are two vessels in the Type 919 Class.

China also has an interesting ‘medical evacuation ship’ called the Zhuanghe which is a converted 30,000-tonne container ship.

She can be equipped with various combinations of containerised shelters, although it does seem the range of facilities is relatively limited

Apart from China, Russia, and the USA, there are also a few other appealing designs to consider

The Spanish Esperanza del Mar is a civilian vessel used to provide medical cover for Spanish fishermen off the coast of Africa.

The Brazilian Navy Soares de Meirelles, which is a riverine vessel used to provide healthcare to remote communities.

The Soares de Meirelles has a very shallow draught to enable it to navigate Brazil’s numerous rivers.

Finally, the Indonesian KRI Dr Soeharso, a converted LPD.

All of the above examples are government owned and operated, mostly by naval forces.

Mercy Ships is a UK-based faith charity that operates two ships

Africa Mercy is a hospital ship with 82 beds and a full range of modern diagnostics and support facilities. They also operate a screening and minor surgery facility on land, whilst ensuring that multiple training and infrastructure development activities are delivered during their stays at various locations.

And the Global Mercy.

The Global Mercy is the largest charity-run hospital ship in the world. The 174-meter, 37,000-ton ship has six operating rooms and houses over 600 volunteers from around the globe representing many disciplines, including surgeons, maritime crew, cooks, teachers, electricians, the host staff and more. The ship also features a 682-seat auditorium, student academy, café, shop, and library – all of which have been designed to accommodate up to 950 crew onboard when docked in port.

The Global Mercy is a purpose-built design, not a converted ferry or RORO ship.

Although not nautical, Orbis is a similar UK charity that specialises in eye care.

They operate in a capacity of both doing, training and capability development, including some very advanced telemedicine, but with the obvious difference of operating from an ex Fed-Ex DC-10, not a ship.

Both Orbis and Mercy Ships are not responding organisations, they work on a planned basis to both deliver services and develop local organisations and capability, but interesting nonetheless.

Before reading on, would you mind if I brought this to your attention?

Think Defence is a hobby, a serious hobby, but a hobby nonetheless.

I want to avoid charging for content, but hosting fees, software subscriptions and other services add up, so to help me keep the show on the road, I ask that you support the site in any way you can. It is hugely appreciated.

Advertising

You might see Google adverts depending on where you are on the site, please click one if it interests you. I know they can be annoying, but they are the one thing that returns the most.

Make a Donation

Donations can be made at a third-party site called Ko_fi.

Think Defence Merch

Everything from a Brimstone sticker to a Bailey Bridge duvet cover, pop over to the Think Defence Merchandise Store at Red Bubble.

Some might be marked as ‘mature content’ because it is a firearm!

Affiliate Links

Amazon and the occasional product link might appear in the content, you know the drill, I get a small cut if you go on to make a purchase

RFA Argus and Beyond

The UK Government does not operate a hospital ship, instead, RFA Argus is a Primary Casualty Receiving Ship of the Royal Fleet Auxiliary.

She has an interesting history.

During the 1982 Falkland Islands conflict, the Contender Bezant was utilised as an aircraft transport, ferrying helicopters and Harriers south to the Falkland Islands.

Following purchase by the MoD in 1985 for £13million, she was converted to an aviation training ship at Harland & Wolff, Belfast, with the addition of extended accommodation, a large flight deck, aircraft lifts, naval radar and communication equipment.

A Primary Casualty Receiving Facility was added before Argus deployed in 1991 to the Gulf War.

Another role of RFA Argus was that of RORO vehicle transport with vehicles carried in the hangar and on the flight deck, a role she performed supporting United Nations operations in the former Yugoslavia.

During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Argus was again present in the Persian Gulf as an offshore hospital for coalition troops, earning the nickname ‘BUPA of Baghdad’.

More recently, RFA Argus participated in OP GRITROCK, the UK’s response to the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone.

She even had a star turn in the Brad Pitt film, World War Z.

The 1998 Strategic Defence Review stated that the MoD would ‘acquire an additional 200-bed primary casualty receiving ship’ with a second available on contract at longer notice (up to a year) when required.

The assumption was that the second vessel could be a conversion project, completed on demand. An IPT was formed in 1998 to start the project and scoping contracts let for initial concept and requirement work with BMT and Atkins. This initial work also envisioned JCTS would be delivered through a PFI rather than outright purchase, but after it was shown there would be little scope for alternative revenue generation the requirement was changed.

After some progress on JCTS, the project was shelved in 2005. There was also some discussion and a proposal to convert one of the Bay class vessels to a JCTS at a reported cost of £360m in 2005, but this didn’t proceed either.

At 28,000 tonnes, RFA Argus is a considerable vessel, and it is the space that allows it to have such flexibility and capability. RFA Argus has a range of extremely impressive medical and support capabilities, improved over many years and refit periods.

In 2009, a £37m programme, for example.

This has encompassed major equipment upgrades to safety and evacuation systems, sewage treatment, refrigeration, ventilation, reverse osmosis, fire and watertight integrity; the removal of the forward aircraft lift; the extension of the PCRS with a new access ramp and two new lifts; new PCRS equipment [including a CT scanner, sterilisation equipment and an oxygen concentrator]; and a series of structural modifications including new steel bulkheads, watertight doors and a new bridge front. There was also a major accommodation upgrade, plus extensive painting, mechanical and electrical packages.

The Role 3 medical facilities can flex but in the largest configuration is designated as 4/4/10/20/70 which means 4 resuscitation bays, 4 operating tables, 10 intensive care beds, 20 high-dependency beds and 70 general beds (in two wards).

Other facilities include dental surgery, imaging (Ultrasound, 64 slice CT and X-Ray), pathology, pharmacy, and physiotherapy. She has an oxygen concentrator and various laboratories.

The Maritime Aviation Support Force often deploys support teams to RFA Argus on a demand basis, and the 180 medical personnel are drawn from the joint defence medical service and wider NHS.

Regular training and exercises not only ensure the professional medical standards are maintained but also that they can be exercised on board the ship, with the various unique factors that this involves, something often overlooked by many when discussing this.

She will eventually need replacing.

RFA Argus out of service date was recently extended beyond 2030, nearly fifty years of service to the Crown.

A 2022 answer is response to a House of Comms Defence Select Committee request provided some insight into life beyond RFA Argus.

“Will RFA ARGUS’s retirement date be extended until the dedicated primary receiver MRSS is operational and will the MRSS be configured to offer the same level of casualty support as the ARGUS?”

Royal Fleet Auxiliary ARGUS will be extended in service beyond 2030.

Beyond ARGUS, the MRSS programme will offer an enduring solution to afloat medical support.

The future Maritime Deployed Hospital Care (MDHC) capability hosted by the MRSS will be based around scale and effects required to support Littoral Strike.

It is anticipated that this will be broadly equivalent to the level of capability that ARGUS currently provides now.

Given there are planned to be more than one MRSS, there could be opportunities to disaggregate medical capability between multiple platforms, with an option to re-aggregate in time of crisis, rather than only operating a single platform. MRSS is still in the concept phrase, and the precise laydown of the medical capability is still being developed.

The Multi Role Support Ship (MRSS) is now in concept stage, with industry proposing various ship designs to meet the requirement.

Navy Lookout has a great summary of some of these emerging designs.

To summarise, the future of the PCF is tied to MRSS.

But, there may be other pathways, and that is Part 2 of this series.

Discover more from Think Defence

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Another (in)famous hospital ship was the Russian 'Orel' that was responsible for the detection of the Russian fleet at Tsushima in 1905. She was sailing at the tail end of the fleet as it attempted to pass through Tsushima Straight in fog. But she did so with lights burning as was required by treaty and drew the attention of a Japanese cruiser which then detected the rest of the fleet.